Access to a safe, legal abortion remains one of the most consequential barriers women face in Latin America and the Caribbean today. Every country in Latin America and the Caribbean except Guyana restricts access to abortion to some extent. Six countries in particular—the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Suriname—maintain the most extreme stance on this issue, either explicitly or by omission, denying women access to abortion even in cases where it could save the mother’s life. Chile recently loosened its restrictions on abortion to permit it in three specific cases: to save the life of the mother, in situations when the fetus is not viable, and when a pregnancy is the product of rape.

In Bolivia, one out of every 160 women dies during the childbearing process, one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the Western Hemisphere—compared to one of every 3,800 women in the United States. There are many reasons that carrying a pregnancy to term in Bolivia remains incredibly risky—Bolivia has the lowest national health expenditure per capita in the Americas, and women in Bolivia experience the highest rate of intimate partner violence in all of Latin America. The third leading cause of maternal deaths in the country is complications related to unsafe abortions. Estimates indicate around 44,000 attempted abortions lead women to seek emergency medical attention each year.

In the past three decades, ample research has demonstrated that maternal death increases chances of infant death in low-resource communities. A 2015 longitudinal study based in Ethiopia, for example, concluded that among maternal deaths recorded, 81% of their infants also died. Most of the women documented in this study were already mothers, meaning they also left other children behind.

According to a report conducted by Ipas, a reproductive health NGO, 71% of women in Bolivia who sought abortions in 2011 already had children, and 84% were married or in a relationship. When a mother dies in Bolivia, who is she leaving behind, and how many are dependent on her life for survival? Many of these deaths would be preventable if not for the criminalization of abortion.

These figures must be considered in the context of decades of restrictive “legal” status of abortion in the country. In 1973, the dictatorship of Hugo Banzer altered Bolivia’s penal code from total prohibition to permitting abortion in special cases with medical and judicial permission, similarly to Chile’s recent restriction—although abortion in Bolivia was permitted in cases of incest, not cases of unviable fetuses. This shift occurred as awareness of infant and maternal mortality in Bolivia was increasing, which Banzer saw as a threat to the image and credibility of his growing, modern nation. Unsafe abortion was considered a contributing factor to maternal death, particularly for women living in rural areas. While broadening the penal code to protect women carrying involuntary or dangerous pregnancies, in practice, legal abortions were nearly impossible to get, given limited access to the courts and to hospitals. By 1999, only one legal abortion had been performed in Bolivia.

When the Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement Toward Socialism, MAS) government, led by Evo Morales, came into power in Bolivia in 2005, public health, feminist, and pro-choice advocates pressured the new government to address this dated penal code for its unrealistic expectations and damaging outcomes.

Under the 1973 penal code, violence against women has often led to imprisonment or forced pregnancy. Facing this incredible barrier to safety, autonomy, and well being, women often disregarded the law and carried out the dangerous practice of clandestine abortion.

But only after the infamous case in 2012 of a Guaraní woman who was tried and imprisoned for attempting (and failing) to terminate a pregnancy with pills after she had been raped did the Morales administration reduce sentences and penalties for abortion. In theory, the law should have protected this woman, since her pregnancy was the result of rape, but she was sentenced to prison because she had not sought judicial permission to obtain an abortion. This case highlighted the compounding injustices women face in Bolivia, particularly Indigenous women who live without accessible medical attention. In 2014, the Bolivian Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal ruled that abortions in one of the three cases would no longer need judicial approval to be carried out legally.

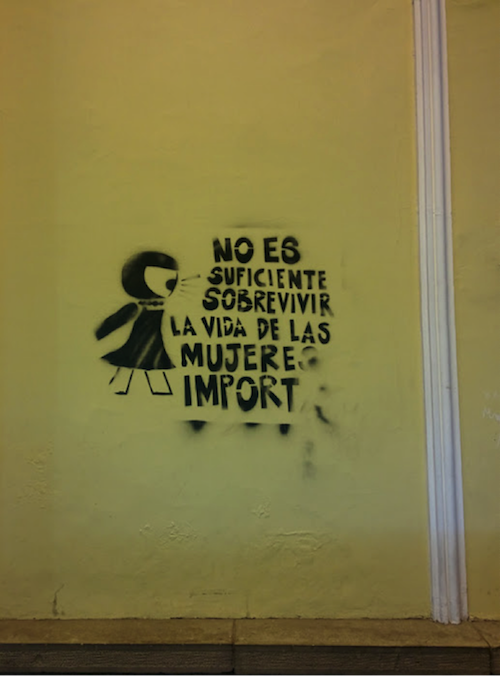

In Cochabamba, Bolivia, this summer, marches and demonstrations from pro-life and pro-choice factions occupied the streets and the airwaves, struggling to sway public opinion regarding a newly proposed amendment to Article 157 of the penal code. This amendment would broaden the decriminalization of abortion, with a proposal to authorize abortion in the first eight weeks of pregnancy in the case that a woman already has dependents, is a student, or is in extreme poverty. As tensions heightened, activists increased their visibility by claiming public space in the city—sometimes with officially sanctioned banners in the Plaza 14 de Septiembre and the Cochabamba Cathedral, and sometimes with unofficial tactics, such as graffiti and slogans announced on intercoms.

In the current debate over Article 157, the pro-life faction brings great energy to their campaigns to eliminate abortion. Despite this, they do not support programs that could prevent unplanned pregnancies, like free contraceptives and integral reproductive health education. While many Catholics oppose the use of contraception, the Pope himself has even moderated some of his statements against birth control in the wake of the Zika crisis—but this view has not appeared to extend to pro-life advocates in Cochabamba, and Bolivia, today.

Contrary to the rhetoric that many governments in Latin America relay, which aligns with the views of the Catholic Church, criminalizing abortion does not seem to reduce its occurrence. Research by the Guttmacher Institute has indicated the opposite: criminalization leads to an increase in abortion in covert and unsafe ways. There is debate as to why criminalization correlates with a higher rate of abortion. A possible explanation is that countries where abortion is prohibited tend to be hostile toward reproductive health more generally. Therefore, many women do not have access to preventative measures such as reproductive education or contraception, leading to unintended pregnancies.

According to Dr. Edgar Valdez, the Director of the Institute for Human Development—Bolivia (IDH) in Cochabamba, the topic of sexual health is perceived as taboo. “Everywhere, especially in the southern zone, it is part of our culture,” he said in an interview this summer. “Most of the people in this area are migrants from the rural area, and it is a taboo, they cannot talk about this, we do not have to talk about this.”

Meanwhile, the pro-choice faction is advocating not only for increased access to contraception but also for broader reproductive health programs, based in an understanding that a woman’s claim to bodily autonomy goes beyond the right to choose.

“I have my position, I support abortion,” Dr. Valdez said. “I think that women have the right to decide I think the best way to avoid abortion is sexual education… The fundamentalists refuse to speak of sexuality, they don't want sexual relations, they don't want contraceptives.” He continued: “I am a Catholic, I have my conception, but I never mix religion with my work, as it is public health that give[s] them [the public] all the alternatives.”

On July 7 of this year, the lower house of the Plurinational Legislative Assembly agreed to amend Article 157 of the penal code to permit abortion in the first eight weeks of pregnancy in cases where a woman already has dependents, is a student, or is living in extreme poverty. Furthermore, according to the new code, a woman could terminate their pregnancies in the case of one of the “three cases”—in the cases where the woman’s health is at risk, when the fetus is not viable, when the pregnancy is the result of rape, incest, non-consensual assisted reproduction, or when the pregnant woman is a minor—without restriction. This article amendment was then transferred to the upper house, the Senate, for further deliberation.

In September of this year, the law passed. Now, abortion is allowed during the first eight weeks of pregnancy in cases where a woman already has dependents, or is a student as well as in the cases outlined above. Finally, advocates and policymakers realized the moral shortcoming of ignoring decades of international, interdisciplinary research and that they could no longer justify the risks women take while unwillingly carrying their pregnancies to term.

Notably, however, is the exclusion of legal abortion in cases of extreme poverty, due to contention within the Senate as to how this condition would be defined and applied. Therefore, the pro-choice camp is also disappointed that the law does not go far enough. Even with this sweeping decriminalization, abortion still exists within the framework of criminalization. When the circumstance of women’s pregnancies does not fall within these seemingly liberal boundaries, women who seek abortions are still subject to prison sentences between one and three years. As the specifications allowing for abortion become more liberal, pregnant women who do not meet these specifications must overcome more scrutiny.

Several feminist organizations have grown increasingly skeptical, critical, and active in reaction to the MAS government’s response to abortion. One organization, Por la vida de las mujeres (For the life of women), published a DIY abortion guide for women in Bolivia, and promoted a vigorous, free, and safe abortion campaign in La Paz. Another feminist organization, Mujeres Creando (Women Creating), has also published a number of texts, including Ni el útero abierto, ni la boca cerrada (Neither the open uterus, nor the closed mouth). Mujeres Creando, led by Maria Galindo, has directed many public actions, and have protested in favor of abortion in front of a cathedral in La Paz, as well as launching a South American mural movement known as the Milagroso Altar Blasfemo (Miraculous Blasphemous Altar), which inverts the imagery of the church and the state to elucidate the injustices imposed by regulating the bodies and lives of women.

Both the Por la vida and Mujeres Creando campaign to Bolivian women that they cannot rely on the government for security, nor can they count on it as an ally in the struggle toward their autonomy and liberty. The two groups choose to consciously disobey established laws—by promoting direct action, including abortion on demand—because they regulate women’s bodies, symbolize, and epitomize the patriarchal state. Through their artistic expressions and public actions, they call upon Bolivian citizens to denounce the MAS government—and arguably all forms of government that seek to restrict women’s freedom.

Bolivia has become increasingly polarized politically since Evo Morales’ announcement that he plans to defy the constitution and run for a fourth term in office, which many see as a betrayal of their electoral right to choose. Perhaps this political act will provide a moment of reflection for those who vehemently force women to fulfill their pregnancies, or those who can sympathize with those women who choose not to participate and surrender power to the government at all. While many feel their rights have been violated in this recent ruling, women’s rights have been violated for centuries, and women continue to die because they do not have the right to choose what happens to their body.

On December 6, the Bolivian senate wrote the amended penal code into law. In response, pro-life advocates continued their fervent efforts to oppose abortion, and have begun a hunger strike in La Paz.

Until governments relinquish control over women’s bodies, criminalization will continue to lead to unsafe underground abortion practices, and the needless deaths of many women. Pending this unforeseeable change, many women have no choice but to aborto al sistema.

Jennifer Zelmer is a graduate student in the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University. She is a women’s rights and reproductive health advocate who researches policy and social determinants of health in Bolivia, Guatemala, and the United States.