Women’s soccer in Argentina received unprecedented media attention when its national team went on strike in September 2017 in response to structural sexism in the industry and sport. Argentina does not have a professional women’s soccer team—it is still officially considered an amateur sport—despite significant increases in women’s participation in recent years. Meanwhile, Argentina’s men’s soccer team is known as being one of the best in the world, with its top player Lionel Messi reportedly making $111 million during the 2017-2018 season.

The strike took place shortly after the national women’s team resumed practice following a two-year hiatus due to internal issues in the Argentine Football Association (AFA), the governing body of this sport in the country. Women’s soccer was not high on the association’s list of priorities—which included the election of a new president and the restructuring of the entire organization, such as new leadership, participation in new tournaments, and negotiating television contracts.

The strike occurred in the context of a global feminist movement demanding gender equality for women and LGBTQ communities. In Argentina particularly, this labor dispute has gained momentum through social movements including Ni Una Menos and other forms of feminist activism sweeping through Latin America, Ireland, Poland, Spain, the United States, and beyond, fighting not only for reproductive freedom and autonomy but also against machismo and violence against women. The movement is committed to furthering a new, fourth wave of feminism to overcome the patriarchy.

In a letter to Ricardo Pinela, president of the Committee on Women’s Football of AFA since April 2017, the players explained the central motives for their dissent:

We write to you as the players who form Argentina’s Women’s National Team, because as protagonists of this sport, we recognize that, for it to grow, support is necessary, and we need to fight for our rights. [...]

As practitioners of an amateur discipline, those with work obligations must often choose to miss work or arrive tardy, which can be detrimental to their salary, which they are forced to sacrifice in order to participate in scheduled friendly matches and/or international tournaments. We are obliged to demand that the corresponding stipend be an amount in accord with our aforementioned needs. [...]

Based on the damages incurred by the[se] situations, and until AFA offers the means necessary to rectify them in a proper manner, we declare our decision NOT to present ourselves for the convocation realized by said entity. The members of the Women’s National Team stress our desire to search collaboratively for solutions to improve present conditions and build upon these toward a better future.

In the past, AFA had always paid a minimal daily stipend of approximately $10 USD to players called up for national team duty. But after the women’s team was finally called back into action after two years of dormancy, the players were denied even this compensation. Despite half-hearted attempts by AFA to reach an agreement which included offers of a stipend even lower than the historical amount—around $8.50 USD—the players decided to organize themselves to stand up against years of neglect from AFA and take action by refusing to attend practices. Though the stipend was the main motive behind the players’ decision to strike, other issues including being forced to train on artificial turf while the youth men’s teams trained on the complex’s impeccably-groomed natural grass fields also played a role.

The players’ response and open letter to Pinela stirred an unprecedented uproar in Argentine media that ended the long-standing invisibility of women’s soccer. The strike revealed issues with compensation as well as travel. For example, during a trip to Uruguay for an international match, players traveled overnight, were not provided with a hotel, and were only able to rest on a bus prior to the game. They cite training conditions at AFA’s complex—inadequate fields, locker rooms, and clothing—as necessary improvements to begin to give women equal treatment in the sport.

Although AFA’s president, Claudio “Chiqui” Tapia has publicly expressed support for the women’s teams, he continues to marginalize and exploit AFA women players. In a statement during the opening ceremony for the 2017-2018 AFA women’s league, Tapia referred to himself as the “president of gender equality” because of his “strong commitment to the development of women’s football.” Yet the reality does not reflect this rhetoric.

A law enacted in October 2015 states that both women and young adults between the ages of 18 and 29 must make up 20% of the directive committees for civil sports associations in Argentina. This includes both AFA and the Olympic Committee.To comply with these new requirements for greater female representation, the AFA appointed María Sylvia Jiménez to the executive committee, the first woman since the organization’s founding in 1893.

However, among the new authorities to head the Women’s Football Committee, two men, Ricardo Pinela and Jorge Barrios, were appointed to the positions of president and vice president, while Bárbara Blanco was elected to the position of Secretary. Nevertheless, this mostly male panorama is bound to change, at least institutionally: the South American Football Confederation (CONMEBOL) enacted a new requirement that as of 2019 South America clubs wishing to participate in men’s international tournaments must also have women’s soccer teams, though AFA has not taken steps to ensure that conditions for these new teams will be up to standard.

Argentina’s participation in the April 2018 Women’s Copa America, hosted by Chile, gave the country a chance to qualify for the 2019 FIFA Women’s World Cup in France—following a 12-year period where Argentinian women did not participate—giving unprecedented exposure to the precarious conditions the Argentine women’s soccer team faces. Through publications on social media and interviews with Argentine newspapers and radio programs, national team players capitalized on their on-the-field success and expressed their unrest about the scant support they received from AFA, reinforcing the stereotype of soccer in Argentina as a “cosa de hombres” (“man’s thing”).

From its amateur roots in the 1800s to its rapid popularization and eventual professionalization in the 1930s to its mass commercialization in the 1980s, women have been systematically left out of the country’s official soccer narrative—though unofficial women’s leagues have been reported as early as the mid-20th century. In recent years, most of South America’s women’s national teams, including Argentina, have dropped out of the FIFA rankings due to a lack of international competition since the federations of CONMEBOL have almost exclusively dedicated their resources and attention to men’s football in their country.

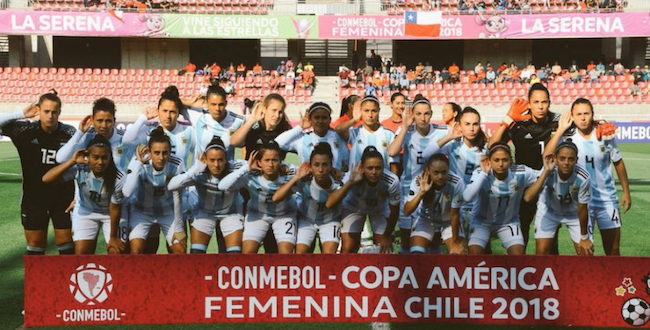

This year, Argentina earned a spot in the final round of the tournament, their first televised match during the women’s Copa America. In the official team photograph, the 22 Argentine players posed prior to the match with Colombia with their right hands cupped behind their ears—an homage to the famous Topo Gigio goal celebration by soccer player Juan Román Riquelme, considered among one of the most creative players in South American soccer history. Riquelme had used the gesture while celebrating a goal to protest the administration of his club, Boca Juniors of Buenos Aires, unsatisfied with the negotiations for his contract renewal. The women’s national team adapted the famous gesture as a demand to be heard and seen by their country and by AFA.

The players’ “silent” protest had further reaching repercussions than expected. Many of Argentina’s major newspapers began discussing the status of women’s soccer. However, the interviews and articles were mainly focused on the conflict with AFA—including disputes over stipends, uncertainty over prize money for tournament results, and inadequate uniforms for players. The media failed to mention the team’s soccer achievements or any actual analysis of its competition in Chile.

The Copa America in Chile, beyond offering an opportunity for World Cup qualification, also provided a stage for players to say “enough is enough,” in the context of the women’s rights movements currently taking place in Argentina and beyond. The climate seems ripe for their voices to be heard as these players fight for progress.

Thanks to a third place finish in the Copa America, Argentina’s next challenge is the November playoff for a place in the 2019 World Cup against the country that finishes fourth in the Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF) World Cup qualifier. The players are already seeing a response from AFA, which has promised to provide the best conditions possible in preparation for the playoff, including a tour to North America for a series of international friendly matches and various weeks of intensive training at AFA’s complex in Buenos Aires.

Nevertheless, national team players are still skeptical, given their past treatment and previous unmet promises. They are taking steps to organize themselves alongside other female players in local tournaments and leagues by creating a players’ union—an effort still in its early phases. The women of the Argentine national team will continue to lead the way for their fellow players, toward equality and the eventual professionalization of their sport.

Gabriela Garton is currently a goalkeeper on Argentina’s Women’s National Football Team, her first call-up was in 2015. She is a Master’s student in Cultural Sociology and Cultural Analysis at the Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales (IDAES), University of San Martín (UNSAM). She received a doctoral fellowship from the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) and is a researcher with the Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani at the University of Buenos Aires (IIGG/UBA). Find her on twitter: @gaby_garton

Nemesia Hijós is an Assistant Professor at the University of Buenos Aires. She is a Master’s student in Social Anthropology, Instituto de Desarrollo Económico y Social (IDES), Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales (IDAES), University of San Martín (UNSAM). She received a doctoral fellowship from the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) and is a researcher with the Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani at the University of Buenos Aires (IIGG/UBA). Find her on twitter: @nemehijos