For more than half a century, the NACLA Report has offered a master class in historiography, simultaneously capturing the episodic, the conjunctural, and the structural determinants of political change. And it has done so in what seems like real time, despite being published just once every few months. At its 1966 founding, NACLA embodied the promise of a moment in New Left scholarship when totality and contingency weren't seen as opposing viewpoints, but rather self-reinforcing. The uniqueness of such a perspective really can't be emphasized enough: a “report” on Latin America in the 1960s could easily have fixated exclusively on U.S. interventionism, on the way external, neo-colonial forms of power shape and distort local experience.

But the Report on the Americas, over the years, has repeatedly managed to keep the balance wheel steady, neither focusing solely on foreign intervention at the expense of domestic dynamics, nor emphasizing a structural and class analysis of global capitalism to the exclusion of contingency, culture, and ideology. Even as academics in their seminars came to debate what has since come to be known as intersectionality, NACLA, in practice, had long been revealing the interlock of race, gender, sexuality and class. Already by the time I had entered a doctoral program in history in the early 1990s, NACLA's holistic perspective had become so ingrained, such a powerful matter of common sense, that it took some time to realize that historians of other regions didn't reflexively set the conjuncture within the structure to account for current crises. Really, the method deserves its own name. NACLismo?

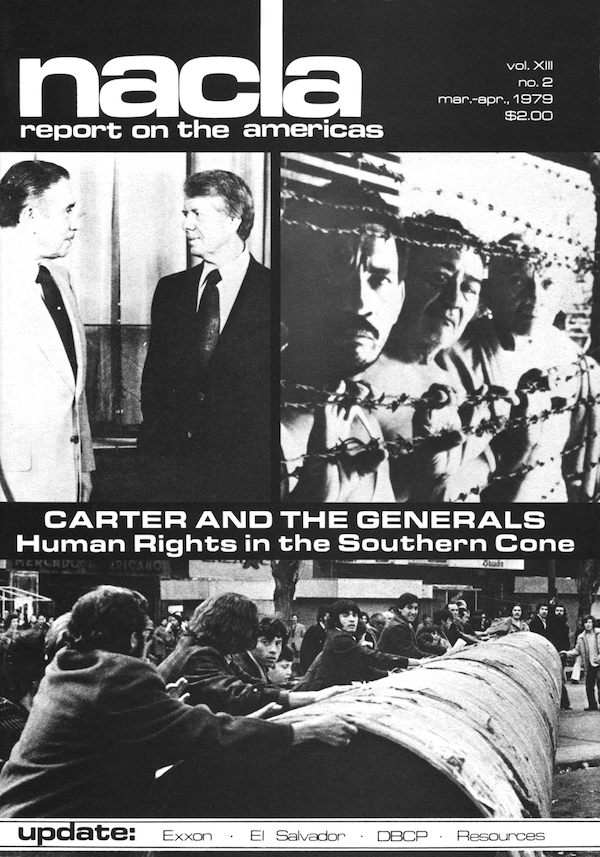

“The Long Night of the Generals” is a perfect example. At the time of its publication, in 1979, Bolivia, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina had fallen to right-wing military dictatorships. NACLA had been covering the post-Cuban Revolution radicalization of Latin America's Left and Right for over a decade, and so the collective authors of the essay— Amalia Bertoli, Roger Burbach, David Hathaway, Robert High, and Eugene Kelly—recognized this “long night” for what it was: a rupture with the region's postwar political consensus; the emergence of a new kind of ideological militarism; the defeat of the southern cone's powerful and mobilized working-class movement (which the authors hoped would be temporary); and the beginning of a set of economic policies that have since come to be known as neoliberalism.

Published in a special issue entitled “Carter and the Generals: Human Rights in the Southern Cone,” the essay's analysis seems as valuable today as it was over three decades ago. One particularly striking theme is the degree to which the crisis politics that overcame Latin America in the mid-to late 1970s was an extension of crisis in Southeast Asia. With the U.S. driven out of Vietnam, the generals understood their struggle as opening a new front in a larger global battle. The details remain priceless. Chile's finance minister, Sergio de Castro, telling local dairy farmers who can't compete with powered- milk imports “to eat their cows” is as vivid an illustration of the carnivorous proletarianization of small-holder production as anything found in Capital. Eduardo Galeano pointing out that the region's Milton-Friedmanite dictatorships don't have to burn radical books: they simply pulp them, with abstract labor transforming abstract thought—Marx, Freud, and Piaget—into paper napkins used to clean up imported food.

Click here to read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time.