This is the first in series on child migration from the Infancias y Migración Working Group. We’ll have a new article every Friday.

Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

Mario celebrated his first birthday on the journey. It was not much of a birthday, of course—he was more than 2,000 miles from home, in a foreign country, and separated from his parents and most of his siblings.

A few months earlier, armed men had burst in on a family gathering and kidnapped nine children, including Mario and his siblings. The captors released the children several days later, but the episode made clear their lives were under threat. His parents asked close friends, a couple, to spirit Mario and his seven-year-old brother out of the country and away from danger. Their sisters were supposed to depart with their grandparents some time later.

Mario and his brother arrived to safety and they expected to reunite with the whole family. But they never saw their parents again. Six months after Mario’s departure, on the eve of their own flight to safety, his father was murdered by military forces, and his mother, who was pregnant, was tortured and disappeared.

Mario’s story echoes those of countless Central American children in recent years who have fled horrific violence in their home communities and crossed borders in search of refuge. But this is not a story about Central America, nor a story from the present. Mario’s flight occurred in 1976, at the height of Cold War-era repression of the Latin American Left. Mario’s father, Mario Roberto Santucho, was the head of one of the hemisphere’s largest Marxist guerrilla organizations. The country from which the siblings fled was Argentina. Their destination: Cuba.

The differences between Mario’s experience and that of contemporary Central American child refugees are of course varied and profound: the political context, the nature of violence, the geopolitical meanings of the children’s flight for both the sending societies and the receiving ones—not to mention what happened to Mario and his siblings once they arrived at their destination. The Cuban state, thanks to its political affinities with their revolutionary parents, embraced the children, offering protection first in the Cuban Embassy in Buenos Aires and then once they arrived in Havana.

Yet the parallels between these two very disparate child refugee stories are also instructive. Posing the comparison in the first place invites us to think about the cross-border movement of Central American children in recent years not as exceptional and without precedent but as part of a longer history of child mobility in the hemisphere. It invites us to think as well about young refugees who have crossed borders other than the one that divides the United States from Mexico. It invites us, in short, to consider child migration as a social and political phenomenon and to explore the varied ways it has developed over time and across the hemisphere.

Together with a transnational, interdisciplinary group of colleagues working on the politics of child migration, we have put together a series of essays examining these questions. Collectively, the essays that will be published in coming weeks invite us to consider: To what extent does child migration have its own patterns, logics, politics, and geographies, distinct from migration involving adults? What do we learn from treating it as a distinct phenomenon, both empirically and politically? These questions are of urgent importance given both the significant numbers of young people on the move across the hemisphere today as well as the political hypervisibility of child migration.

The Birth of a “Crisis”

In 2014, the media began reporting on the “surge” of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. But what distinguished that moment, and border apprehension patterns ever since, was not the absolute numbers of border crossers, which were low by all historic comparisons. Rather, it was the demographic profile of the crossers—and specifically, the proportion of children among them. Increased numbers of unaccompanied children (UACs) crossed the border in 2014— 68,541 according to Customs and Border Protection—as well as 68,445 “family units,” a designation that U.S. immigration agencies use to refer specifically to a group comprised of a child or children traveling with their parent or parents. All told, the numbers of UACs increased by 77 percent and that of families by 361 percent compared to the previous year. The defining “problem” that emerged at the border in 2014 was thus not migration in general but child migration specifically.

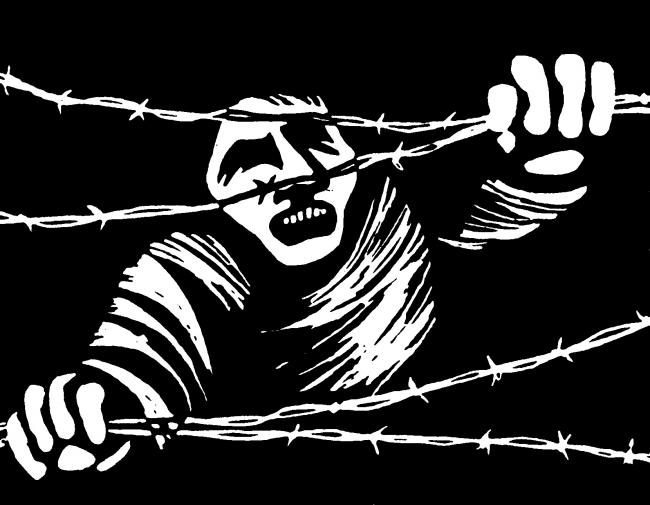

In a sense, the hemisphere has been living in the shadow of 2014 ever since. The numbers of child migrants, both UACs and those in family units, have fluctuated but remained high. The events of 2014 catalyzed the establishment, under the Obama administration, of the United States’ current family detention apparatus, which has since incarcerated tens of thousands of migrant parents and children. The 2014 “crisis” also set the stage for the Trump administration, beginning two and a half years later, to pursue a litany of illegal and cruel policies aimed at deterring asylum seekers, criminalizing them, and decimating the legal protections to which they are entitled under national and international law. Migrant children’s bodies and their emotional traumas were transformed into a political arena to reassert national borders and national security imperatives.

At the same time, the treatment of child migrants has catalyzed searing public rebuke. Of the many devastating policies enacted by the Trump administration, none has provoked more potent and widespread outrage than the family separation policy of 2018 and the “children in cages” uproar in the spring of 2019. Much ink has been spilled, justifiably, to condemn these catastrophic human rights violations. Yet critical examination of the phenomenon of child migration and the category of child refugee has been curiously absent from public debate. Absent too is how states and their institutions have helped to produce new categories of migrant, exiled, and refugee children through violence and punitive actions.

Following Children’s Trajectories

What difference does the child make? The answer, politically speaking, is a lot. Migration involving children is often cast as a specifically humanitarian crisis, a framing that depoliticizes it and treats this form of mobility as if it were exceptional and without historical causes. It also frames young migrants as victims rather than agents.

Anti-immigrant commentators in turn weaponize the innocence of child migrants against their parents. Adult border crossers are more than just criminals: they are morally and culturally unfathomable, parents who have deliberately put their own children in danger. Others suggest migrant children are not so guileless after all. As Trump once put it, “They look so innocent. They’re not innocent,” invoking the polarized discourses of purity and innocence, danger and complicity, so often used to describe the offspring of the marginalized.

At the same time, representations of suffering children lend emotional potency to the advocacy efforts of immigrant rights supporters. So great was the outrage over “family separation” that activists now use this moniker to describe a variety of anti-immigrant policies that have nothing to do with the specific border policy it originally referenced.

These are just some of the ways that the child makes possible certain anti- and pro-immigrant politics. We believe that greater attention to child migration—as both an empirical phenomenon (actual children at an actual border) and as an idea (the discourses and representations surrounding them)—can help inform the work of the academics, advocates, and activists opposing the violent and unjust migration policies that have proliferated across the hemisphere.

This series of articles by historians and social scientists based in half a dozen countries explores different instances of child migration, past and present, as both empirical phenomena and symbolic politics. Drawing on original research, their contributions address contemporary movements of young migrants and asylum seekers as well as older, Cold War-era mobilities of refugees and exiles. They also displace the often-hegemonic focus on the U.S.-Mexico border to consider and compare forms of movement across the hemisphere, including in the Southern Cone and the Andes. They explore children on the move as refugees and asylum seekers, as economic migrants, and as the subjects of child-specific forms of migration, like transnational adoption.

For Mario and his siblings, as for many child migrants today, crossing borders was part of a survival strategy. Mario’s story, like those recounted in this dossier, invites us to consider the context and causes of children’s mobility, the violence they suffer, the role of states and other actors in their trajectories, the resistances they enact, and the possibilities for creating new lives and identities. Revisiting his story also allows us to think about the past and present effects of class and racial inequalities so prevalent in the hemisphere, and the differences between middle-class refugees like Mario and poor, peasant, or Indigenous youngsters. Finally, it invites us to consider how the mobility of children and youth makes possible certain kinds of politics, both repressive and liberating—not only for young people, but for all migrants.

Nara Milanich is a U.S. historian at Barnard College, Columbia University. She works on the history of childhood, family, and reproduction. She has served as a volunteer translator at the largest ICE detention facility in the U.S., the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas.

Isabella Cosse is an Argentinean historian. She works as researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) and Universidad de Buenos Aires and she teaches in Universidad Nacional de San Martín. Currently she is working on a project entitled Family and Politics in the Cold War in Argentina.

Valentina Glockner is a Mexican anthropologist working as a Cátedra CONACYT at El Colegio de Sonora, Mexico. Her work focuses on the intersections of the anthropology of childhood, (im)migration and the State.

About the Working Group: In July 2020, the authors convened the Infancias y Migración Working Group, consisting of 10 colleagues in five countries from a variety of disciplines. This series of articles for NACLA is the group’s first publication project.