This piece appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Translated from Portuguese by Peter Schmidt.

On July 2, 2019, sociologist Vilma Reis announced her intention to run for mayor with the Brazilian Workers’ Party (PT) in Salvador, the capital of Bahia state. In the primaries ahead of the 2020 local elections, her campaign, which became known as the “Agora é Ela!” movement, grew to involve various social movements. At the forefront was the Black women’s movement.

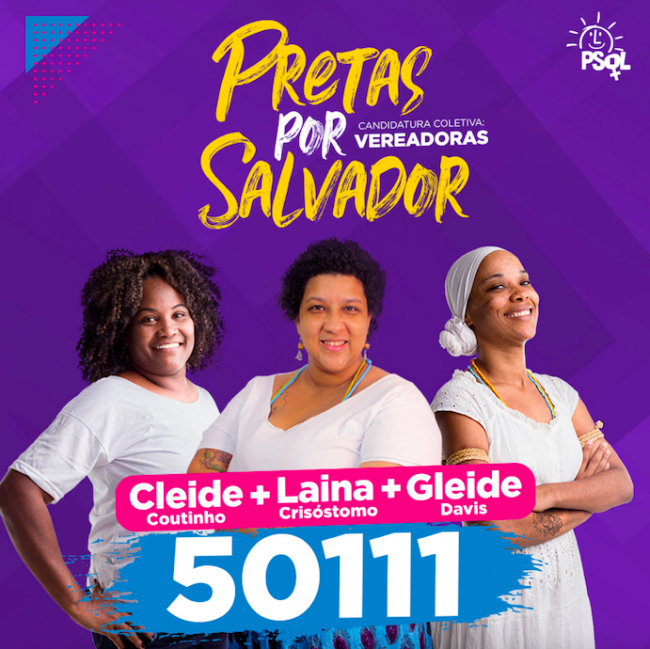

Brazilian politics has seen a significant increase in the leadership of Black women following the 2015 Black Women’s March against Racism, Violence, and in Favor of Good Living in Brasília and the 2018 murder of activist and city council member Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro. Amid the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, Black women maintained a formidable public presence, participating in initiatives such as making and distributing face masks and food, providing assistance to victims of violence, and carrying out sustained action through virtual meetings, seminars, workshops, mobilizations, and other online activities. For these women, communication, principally through social media, has played a critical role not only in advancing their political campaigns, but also in subverting the established order and dominant representations of Black women. In the process, they have built counterhegemonic narratives by constructing new images to represent Black women and the Black community as a whole.

In addition to the increasing number of Black women candidates, the diversity of organizations dedicated to supporting Black women’s leadership stands as a testament to their insurgency on social media and in the streets. Such organizations include Enegrecer A Política (Blacken Politics), Black Women Decide, and I Vote Black. Another important example is the Marielle Franco Permanent Forum for the Political Strengthening of Black Women, or simply the Marielles Forum. The Forum was created through a gathering of Black women in Salvador on March 14, 2019—the first anniversary of Marielle’s killing—to pay her homage and protest her brutal murder. The Forum aims to stimulate Black women’s participation in positions of political leadership—whether as members of homeowners’ associations, school administrations, or university councils or as lawmakers at the municipal, state, or federal levels—and to promote their favorable reception. The 2020 municipal elections reaffirmed that Black women, to borrow a phrase from Marielle Franco, are “diverse, but not dispersed.”

Ahead of the 2015 Black Women’s March, the Black women’s movement published an open letter expressing its call for a new social pact at the national level. “As leaders, we offer the Brazilian state and society our experiences as a way of collectively building another dynamic of life and political action, which is only possible by overcoming racism, sexism, and all forms of discrimination responsible for denying the humanity of Black women and men,” the letter stated. “We declare that the building of this process begins here and now.” The letter detailed several key demands that were later at the core of Black women’s electoral campaigns, including the right to life and liberty, the promotion of racial equality, the right to work, the right to education, the right to justice, the right to housing, land and city, the right to public safety, and the right to culture. Another key struggle for the movement is the fight against the mass incarceration of the Black population.

Unlike the notion of “waves” used to describe mainstream feminism, this movement defines itself as a Black feminist tide. This characterization marks a rupture, given that the other feminist waves did not include Black feminist contributions. It also alludes to the place where Black women from traditional and quilombola communities find sustenance: the sea. The message is clear: we will tell our own history!

Indeed, as coauthor Angela Figueiredo has documented elsewhere, the growing body of research on racial and gender-based inequalities—produced both within and beyond the academy—has fueled feminist struggles and their use of digital platforms, amplifying Black feminist activism and giving rise to Black feminist cyber-activism. Engagement with and promotion of these tactics has come from Black feminists of differing perspectives, including those who self-identify as decolonial, abolitionist, intersectional, lesbian, or otherwise.

In the political sphere, the Black feminist tide seeks to redefine spaces of power. It aims to combat conservative forces’ politicized use of women candidates as a function of their need to comply with the law requiring that women make up 30 percent of candidates for public office. As the Marielles Forum stated in an open letter in support of Vilma Reis’s campaign, distributed in person and published in early 2020 on the Forum’s Facebook page, many of these candidates “represent fundamentally masculine interests and agendas,” amounting to “a kind of transmutation of masculine ideals into feminine bodies.” Instead, the statement argued in favor of autonomy for women candidates and alignment between their autonomy, competence, and assumption of relevant responsibilities vis-à-vis social movements. Although Reis’s mayoral primary campaign was ultimately not successful in securing the PT’s nomination in Salvador, her Agora é Ela! movement and the candidacies of other Black women have helped advance this alternate vision of politics and representation.

Social Majority, Political Minority

According to data from the Superior Electoral Tribunal (TSE), the number of women voted into office in the 2018 general elections increased 52.6 percent compared to 2014. In the lower house of Congress, 77 out of 513 seats were filled by women, of whom 13 were Black and only one was Indigenous. This marked an increase over 2014, when 52 seats in the lower house were occupied by women, seven of whom—1 percent of the chamber—were Black women.

Beyond political parties’ lack of investment in Black candidates, Black lawmakers’ experiences speak to the total isolation they face in occupying a space that was not created with them in mind. Drawing on the work of philosopher and activist Sueli Carneiro, we echo the call to “Blacken” and feminize Brazilian politics in order to combat endemic misogyny and racism. The political participation of Black women in legislative spaces is critical.

Forces of socialization have long reproduced and perpetuated negative social conceptions about Black women, and these conceptions are even reproduced in the images we construct of ourselves. This manifests in the form of low self-esteem and shyness in the face of the systematic devaluation of Black features and stereotypical representations of Black women.

Historically, Black women’s organizations have been instrumental in combating the commodification, objectification, and stereotyping of Black women in Brazil. These organizations have contested and unsettled dominant representations of Black women as enslaved or working as maids or servants, which render them dehumanized and animalized. In doing so, these organizations have strengthened positive reference points and representations of Black women in the context of broader anti-racist struggle.

To resist objectification is to resist dehumanization, feminist scholar Patricia Hill Collins reminds us, and this makes possible new imaginaries that break with dominant representations. In Brazil, Black women’s campaigns counter the hegemonic imaginary of politics that centers on the white male individual. In contrast, during the 2020 municipal elections campaign in Salvador, Black women candidates’ communication tactics included activating horizontal, collective perspectives and using elements that affirmed Afro-Brazilian religious identities.

In resisting dominant discourses, Black women perform precisely what Hill Collins calls for: seizing control of their own images. But combatting established imaginaries is no easy task. It means recreating the impact of representation to construct new paths toward visibility. It means leveraging the act of resignifying as a political tactic that allows Black communities and Black women to examine and disrupt contemporary representations and imaginaries.

Read the rest of the article, available open access for a limited time.

An earlier version of this piece was published in Portuguese in Revista Eco-Pós.

Angela Figueiredo is a professor at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB) and coordinator of the Angela Davis Collective and International Decolonial Black Feminist School. She is a member of the Marielles Forum.

Naiara Leite is a master’s student in communications at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB). She is coordinator of the Odara Institute of Black Women’s Communication Program and member of the Black media collective Revista Afirmativa.