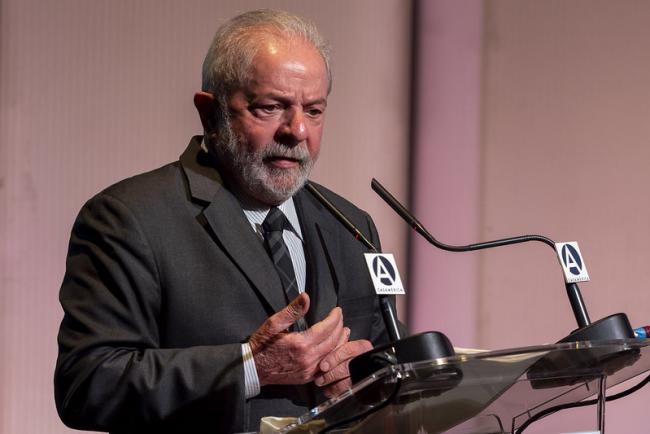

The relevance of the 2022 presidential elections in Brazil cannot be overstated. Close to 160 million Brazilians are eligible to vote this Sunday, October 2. If no candidate receives more than 50 percent of the vote, a second round will take place at the end of the month. Sitting president Jair Bolsonaro is likely to be defeated by former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. If this occurs, the country could start the process of rebuilding its battered democracy after being ruled by the most authoritarian leader in Brazil’s modern history.

The fact that Latin America’s largest nation finds itself at this crossroads is paradoxical given that a decade ago Brazil seemed on the verge of internal democratic consolidation and growing diplomatic relevance. Under Lula’s administration (2003-2011), innovative welfare programs like Bolsa Familia, sustained macroeconomic stability, and an assertive and independent foreign policy created a sense that the long years of dictatorial rule (1964-1985) and economic disarray had become things of the past. But these promising dynamics were abruptly curtailed by the turmoil that has engulfed the country starting in 2013.

It was then that the epidemic of right-wing populism unfolding around the world arrived in Brazil and powerful conservative forces began to reassert themselves, often through non-democratic means. In 2014, conservatives refused to accept Dilma Rousseff’s victory in the presidential elections. This unprecedented move was coordinated by an alliance between right-wing politicians, business and media conglomerates, and a libertarian grassroots movement that took to the streets to demand the impeachment of Rousseff, the country’s first woman president.

By 2014, the country was immersed in an economic crisis and the multibillion dollar Petrobras corruption scandal was unfolding, causing widespread disillusionment with established political systems. Even the incumbent administration, whose party had provided so much—especially for lower-income sectors—was not excluded from public disfavor. Rousseff was finally impeached in 2016 for the alleged misuse of government funds despite a lack of evidence showing her direct involvement. Following her removal, Vice President Michael Temer took office. Under his rule, a new coalition of civilian and military elites set out to revive the traditional neoliberal agenda of the 1990s.

But the popular mandate to do so was missing and political upheavals continued. The disconnect between deeply conservative forces back in power but lacking the legitimacy of votes paved the way for a free-for-all situation in the presidential run of 2018. Mainstream conservative parties couldn’t get traction in the polls and the only truly popular figure, former president Lula, had been illegally barred from running due to a corruption conviction that was finally annulled in 2021. This allowed long-time congressman Bolsonaro to rebrand himself as an anti-establishment candidate who would finally provide top-down answers to what was increasingly seen as a general crisis of the entire political system.

Elected by a Frankenstein-like coalition of free-market ideologues, export agribusiness conglomerates, reactionary military leaders, and morally conservative evangelical forces, Bolsonaro voiced some of the country’s most overtly misogynous, chauvinistic, and anti-minorities narratives in recent memory. He also actively promoted environmental destruction and anti-Indigenous policies, denied the public health threat posed by Covid-19, and worked to prevent the purchase of vaccines. Moreover, he consistently attacked the country’s democratic institutions and appealed to his most vocal supporters to help him establish an overtly authoritarian government.

Although some local governors, members of Congress, and federal judges have challenged Bolsonaro, none of them have been able to entirely mitigate his dictatorial impulses. Only freely held and widely respected elections can democratically purge Brazil of the last rotten remnants of the military regime, which Bolsonaro has openly praised.

After being imprisoned for almost two years on charges now proven to be politically motivated, Lula is, amazingly, now back on the political frontlines, leading an alliance of forces broader than in 2018. Many voters that then supported center-left candidates, such as Ciro Gomes and Marina Silva, now see this election as the real battle between democratic and authoritarian visions for the country.

Lula has signaled that he will reverse many of the anti-labor legislations promoted by Bolsonaro, revive the social expenditure attacked in recent years, and put an end to the environmental destruction caused by the current government. But even if Lula, and democracy, triumph in the first or second round of votes—and if Bolsonaro accepts the results, which he has threatened to dispute—the new government will face tremendous challenges on the national and international fronts.

Domestically, a tough economic situation is likely to linger thanks to the anti-labor and neoliberal policies implemented in the last few years. Likewise, the anti-poverty emergency measures that Bolsonaro put in place, albeit grudgingly, will provoke a dire budgetary shortfall for Lula to manage.

In addition to the political challenges, voters—particularly very poor Brazilians—have high hopes for Lula’s new term in office. But his ability to implement pro-poor social programs will be curtailed, not only by the previously mentioned economic hindrances, but by members of his own centrist coalition. This will likely lead to growing frustration, especially among his main supporters in social movements on the Left. Furthermore, the siren of neo-fascism is strong in Brazil, with the extreme right gaining ground in legislative and judicial institutions, as well as Brazilian society more broadly, and Lula’s victory will not be enough to demobilize that conservative wave.

On the international front, Lula will encounter difficulties that he did not face during his first time in office. The post-Covid-19 socioeconomic situation in Latin America is dire, and many of the diplomatic initiatives for managing regional issues that Lula helped put in place, such as UNASUR, have been dismantled and will thus cannot present a unified regional voice on the international scene. The rising rivalry between the United States and China, especially in Latin America, will also limit Lula. Moreover, in contrast to a decade ago, the BRIC countries are not as unified as before, nor can they serve as effectively as a platform for presenting the demands of the developing world. The global economy is on the brink of a recession, with many countries witnessing rising and persistent inflation, particularly regarding energy prices. Furthermore, the destabilization caused by the current war on European soil distracts the world’s focus from the traditional developmental demands that Lula managed to put forward during his first time in office. Finally, Bolsonaro’s obscurantist foreign policy has tarnished Brazil’s image in the world, and it will take time to repair the damage.

To be sure, several global leaders, such as French president Emmanuel Macron, have expressed sympathy for the prospect of Lula’s return and his promises to mend Bolsonaro’s damage, particularly on the environment. Lula is thus likely to find broad international support for some of his initiatives, but pro-Bolsonaro members of the bureaucracy, particularly in the military, judiciary, and even amidst the diplomatic corps, could slow things down.

Unlike in the United States, Brazil has a national system of election and adopted electronic voting over 20 years ago, which allows for results to be known in a matter of hours. What is more, independent electoral courts oversee the elections, and all parties and media are allowed to monitor the vote counting process, which is widely seen as highly transparent and trustworthy. Yet, much like Donald Trump in 2020, Bolsonaro has been saying that he will only accept defeat if he considers the elections to have been fairly held. Given Brazil’s reliable and transparent election system, his “concern” seems based more on poll results, where he has been consistently trailing Lula.

Clearly, by attacking the results before the election, Bolsonaro is setting the stage for disputing the results and holding onto power illegally. He has pushed for military support, but it is unclear whether he has the backing of the entire armed forces to achieve this goal. But the very fact that this is considered a serious threat is a sad indication of how much damage has produced in Brazil’s democracy by the neo-fascist administration that, one hopes, is soon coming to an end. Still, even if Lula sweeps the election, rebuilding Brazil’s democracy will be difficult, will take time, and will require action and support from democratic forces in Brazil and beyond.

Rafael R. Ioris is a Professor of Latin American History at the University of Denver and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Washington Brazil Office.