This is an excerpt from The Walls of Santiago: Social Revolution and Political Aesthetics in Contemporary Chile (Berghahn Books, 2022).

In the early days of Chile’s 2019-2020 social revolution, known as the estallido social, the presence of the military on the street and the daily curfews recalled for many the excesses of the Pinochet regime, unlocking what historian Steve J. Stern has called a “memory box.” Messages on the walls served to communicate and bear witness to contemporary police violence. “Torture is happening in Chile [in] 2019,” read one prominent stencil. Echoing the 1980s activist phrase “Aquí se tortura,” the stencil referenced the past even as it condemned the present.

![This stencil, “Torture is happening in Chile [in] 2019,” provides a potent denunciation of state violence against demonstrators. (Eric Zolov)](https://nacla.org/sites/default/files/styles/650px_wide/public/en%20chile%20se%20tortura.png?itok=CEktfIPq)

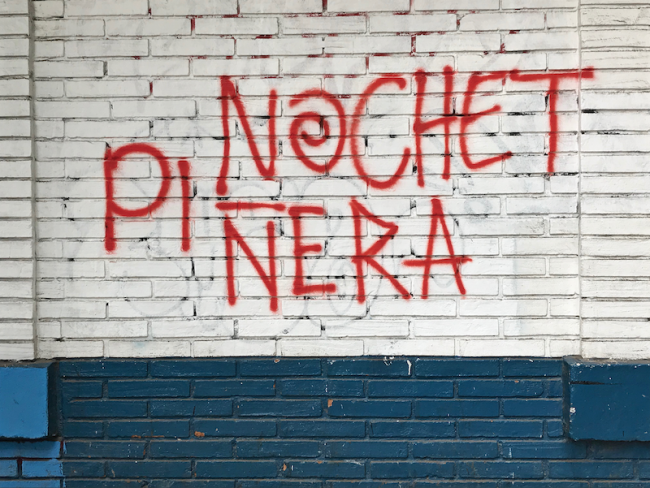

In his remarkable trilogy on the transition to democracy, Stern employs the metaphor of a “giant, collectively built memory box” to capture the space of collective Chilean memory, a chest holding conflicting and struggling memories that may be opened by various triggers. One such trigger was the “state of emergency” declared by President Sebastián Piñera on October 19, 2019. This was the first time the military had been called upon for internal security purposes since the dictatorship. Polemical metaphorical equations between the two regimes were drawn on the walls across the city: “Piñera=Pinochet,” “2019=1973,” “Pi/nochet-ñera.”

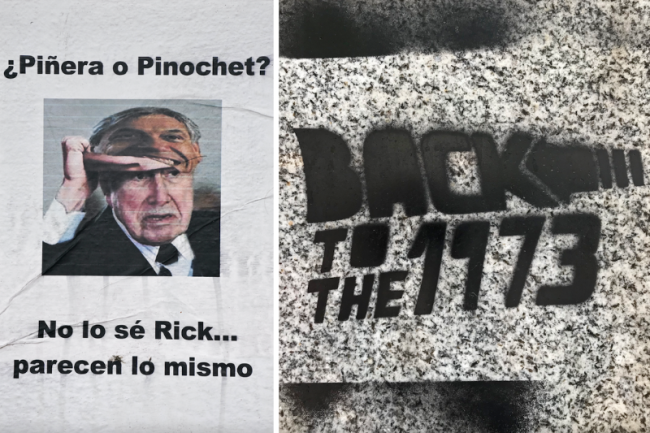

One humorous graphic, rendered through the digital manipulation of an actual photograph, depicts a serious Pinochet in formal attire pulling off a smiling Piñera mask. “Piñera or Pinochet?” asks the caption. Underneath the photo comes the answer: “I don’t know, Rick...They look the same.” The line is a play on the phrase, “I don’t know, Rick. It seems fake,” an expression popularized in a meme based on a U.S. television series, Rick Harrison’s Pawn Stars. Another humorous block print stencil heralds (in English), “Back to the 1973,” drawing on the futuristic logo of the 1985 film Back to the Future—which, interestingly enough, sent its main character 30 years into the past.

Other graphics took a more serious tone. In a striking image plastered along Avenida Providencia, a 1978 photograph of Pinochet surrounded by his generals mirrored in an uncanny fashion a shot of Piñera similarly flanked by his own military advisors. The photograph of Piñera used in this protest graphic was taken at a press conference on October 20, 2019, in which he claimed to be “at war with a powerful enemy” and was clearly staged to demonstrate the full force of the state. As Lili Loofbourow points out, Piñera’s words echoed a statement made by Pinochet in the wake of a 1986 ambush and attempt on his life. “We are in a war,” he had said, “between democracy and Marxism, between chaos and democracy.” A column in The New York Times made a wry observation: “An old but far from forgotten sight is returning to Latin America: presidents facing TV cameras, addressing the nation in a moment of crisis—flanked by their generals.”

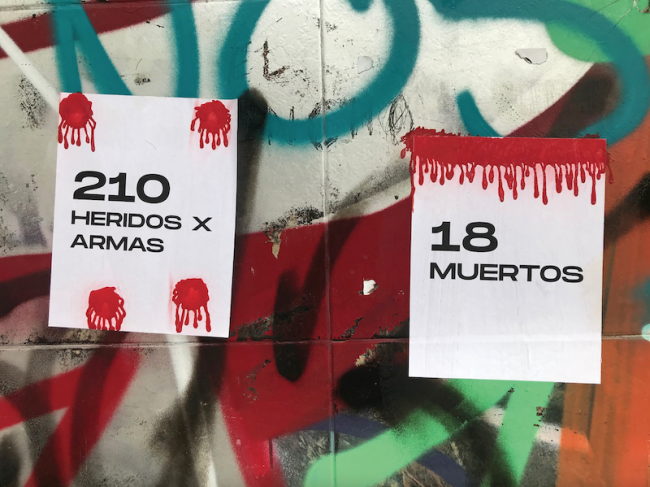

Excessive police force and violence only served to reinforce this comparison. Chile’s national police force, the Carabineros, regularly dispersed crowds with tear gas, chemical water canisters, and hardened rubber bullets, some pointed directly at the heads of protesters. According to the 2020 Human Rights Watch World Report, the Chilean police used excessive and disproportionate force in the social revolution. An early series of blood-spattered prints counted 210 wounded and 18 dead, a number that went up considerably in the course of the estallido.

The violence on the part of the police and the military was so extreme that former president Michelle Bachelet, now the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, spearheaded a special mission to Chile to investigate allegations of human rights violations. The UN “Report of the Mission to Chile,” which covers the period from October 30 to November 22, 2019, affirmed the allegations, determining that there were “a high number of serious human rights violations,” including “excessive or unnecessary use of force that led to arbitrary deprivation of life and injuries, torture and ill-treatment, sexual violence, and arbitrary detentions.” The report also determined that the security forces had failed to distinguish between violent acts and peaceful demonstrations.

On November 17, 2019, Piñera acknowledged police misconduct. Despite “all the precautions,” he said, “in certain cases, protocols were not respected, and there was an excessive use of force.” He added: “[The government] will do its best to assist all victims in their recovery and to ensure that prosecutors and courts fulfill their role of investigating and delivering justice.” In spite of these promises, human rights violations continued throughout the duration of the protests. The National Institute of Human Rights cited in their February 2020 report 3,765 injured people across the nation and 1,835 complaints of human rights violations, including 520 counts of torture and cruel treatment, 197 counts of sexual violence, and 1,073 counts of excessive force.

Moreover, because cases involving security forces are still delegated to military courts, police and military personnel tend to receive minimal sentences for crimes committed in action.

Justice for the Past, Justice for the Present

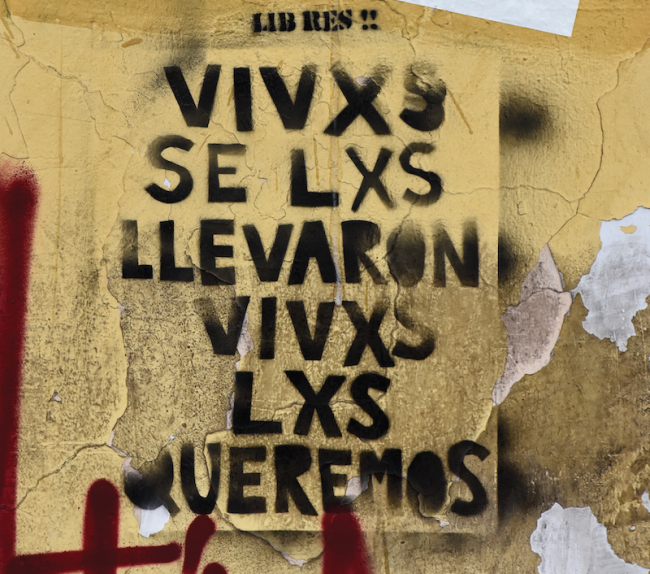

Protesters in the 2019-20 social uprising engaged in a sustained campaign to keep memory alive and visible. The slogan “Alive they took them / Alive we want them back” (Vivos se los llevaron / Vivos los queremos)—born out of the campaigns of the Argentine Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and echoed in Mexico in the search for the 43 disappeared Ayotzinapa students—was a common refrain on the walls. Martyred figures, such as the Mapuche leader Camilo Catrillanca, the “mime” Daniela Carrasco, and the “visible lesbian” Nicole Saavedra Bahamondes, became guiding spirits of the revolution. Photos of such figures appeared all over the city, often accompanied by the injunction: “Justice for…”

Adding to the fliers of los desaparecidos (the disappeared) that have covered the city’s walls in the past three decades have been new announcements of individuals wounded and killed in the recent protests. One poster, for example, depicts a young, dark-haired woman, accompanied by the simple words: “Justicia para Mariana.” The small print provides evidentiary detail: “34 years old, assassinated by the state of Chile / They killed her with a bullet in the face / October 21, 2019.” These posters bear witness to the devastating effects of the police violence in a mode that is public and accusatory.

Whereas fliers of the desaparecidos in Latin America have been traditionally somber, containing an actual photograph and a name, new modes of memory have appeared in recent years. For example, in 2006, painter and sculptor José Rodríguez mounted an installation of giant silhouettes of “los 119” killed in “Operation Colombo,” a sinister 1975 operation in which Chile’s DINA secret police agents murdered and framed 119 youth who belonged largely to the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) party. The silhouettes, which were based on actual photos of the disappeared circulated by relatives, took lifelike form at the plaza in front of La Moneda Presidential Palace and sites of former clandestine detention centers.

In line with contemporary expressive currents, many of the posters in the recent protests had an individual edge. A Maoist-styled lithograph of Yoshua Osorio, for example, depicted a young man with a nose ring, an aura of vibrant black lines radiating out from his face. The text reads: “17 years old / Disappeared and found burnt to ashes at the Kayser de Penca store.” Another poster in this series shows 37-year-old Cardenio Prado drawn with a distinguished face in cubist style with the accompanying text: “Run over during a peaceful demonstration against social injustices.” Kevin Gómez Morgado, a 24-year-old musician, was depicted as a smartly dressed drummer. The text reads: “Assassinated by the military on October 21, 2019 in Coquimbo.” The poster then adds unbearable details: “24 years old. Father of a 2-year-old girl. Lead drummer for the band Los Halcones.”

These stylized posters are powerful and sobering at the same time. They constitute testimonial evidence of the crimes committed, providing names, dates, locations, and descriptions of the acts of violence. They also capture the personhood of the individuals killed, bringing out their singular features and traits. The overwhelming effect of this poster campaign is a city awash in memory. Justice pure and simple—justice for the crimes of the past and justice for the crimes of the present—was a rallying cry of the protests, as is illustrated by this vibrant, massive graphic mural near the Baquedano subway station: “NO MORE IMPUNITY.”

This excerpt has been lightly edited for length and style. For complete figures and endnotes, see the original: Chapter 1 “It’s Not 30 pesos, It’s 30 Years,” pp. 21-46, in The Walls of Santiago: Social Revolution and Political Aesthetics in Contemporary Chile (Berghahn Books, 2022). Excerpt reprinted with permission.

Terri Gordon-Zolov is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at The New School in New York City. She is former director of the Gender Studies Program at The New School and sits on the editorial board of WSQ. Her work has appeared in Latin American Literary Review, The Nation, and NACLA, among others

Eric Zolov is Professor of History at Stony Brook University and was a Fulbright Visiting Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica in Santiago in 2019. His most recent book is The Last Good Neighbor: Mexico in the Global Sixties (2020).