Ahead of Chile’s 50th anniversary of the violent military coup that deposed democratically elected socialist President Salvador Allende, the government of President Gabriel Boric unveiled a National Search Plan to establish the whereabouts of over 3,000 people who were disappeared by the Pinochet regime. The move, welcomed by human rights campaigners, comes as the battle for social progress, truth, and justice is threatened by resurgent denialism and prevailing right-wing dominance over the country’s institutions. This step forward in one area is offset by simultaneous steps back in others.

The anniversary of the 1973 coup takes place in a highly volatile political climate. While mass protests launched in 2019 landed progressive demands on the agenda and representatives in office, the historic initiative to overhaul the 1980 Constitution sparked a fervent backlash. Right-wing disinformation combined with the Boric government’s failure to garner adequate support for the draft progressive constitution led to a defeat of the proposed new charter at the polls.

Now, a new constitutional process, dominated by conservatives, is set to produce an even more regressive legal document. What began as the country’s most promising opportunity to scrap a key pillar of Pinochet’s legacy has instead forced Chileans into a lose-lose situation, in which voters are faced with a bleak choice: keeping the constitution enacted by Pinochet in 1980 or introducing a new charter that will peel back even minor hard-won rights and seal the dominance of the most radical sectors of Chile’s far-right. Five decades after the coup, Pinochet’s shadow hangs heavy.

Chile’s Road to Socialism Violently Quashed

On September 11, 1973, General Augusto Pinochet’s military takeover violently halted the transformative socialist project that began with the election in 1970 of President Allende and his Unidad Popular government. Free-market thinkers enlisted by regime bureaucrats quickly transformed the country into a living laboratory for neoliberal economic experiments, privatizing national assets to be sold to foreign investors. The regime imprisoned supporters of Unidad Popular or purged them from the country via enforced political exile. Military personnel took control of media outlets and educational institutions, replacing directors of companies and university rectors.

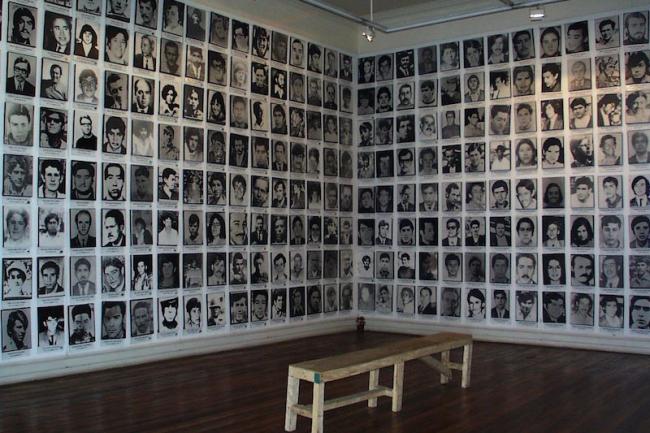

The success of the 17-year regime was enabled by a powerful network of civilians who allowed the military to hunt down, detain, and torture leftists, and who were rewarded for their efforts with land and lucrative positions in Chilean institutions. Augustín Edwards, for instance, owner of Chile’s largest newspaper, El Mercurio, collaborated with the CIA to destabilize the Allende government and foment the coup. After 1973, El Mercurio lent support and credibility to the regime with favorable coverage. This is why Chile’s dictatorship is referred to as a civilian/military dictatorship. Between 1973 and 1989, Pinochet’s regime was responsible for the disappearance of over 3,000 people, the execution of 2,279, and the torture of over 40,000. Some 1 million Chileans went into exile.

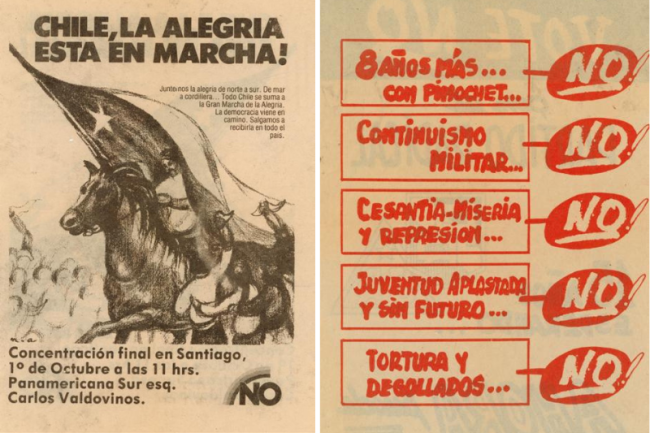

In 1988, Pinochet held a referendum on his rule that he lost. Civilian governments were to oversee a transition toward democracy, but democracy came with a hefty pact stipulating that the junta would enjoy complete immunity from prosecution. Pinochet remained very much a part of public life through the 1990s and remained head of the army until 1998. Although Pinochet’s influence declined after being placed under an 18-month house arrest in London in 1998 for crimes against humanity, the harsh economic model implemented by his administration—and the supremacy of the armed forces—remained unchallenged. After three decades of democratic rule, discontent finally boiled over on October 18, 2019, when mass demonstrations over the cost of living and inequality broke out across Chile.

The uprisings forced the political establishment to agree to a constitutional process to rewrite Pinochet’s 1980 Constitution. The proposed new charter, drafted by a popularly elected Constitutional Convention, promised fundamental change, including enshrining rights for women, Indigenous peoples, and the environment. But a furious campaign of disinformation executed by the unreformed right-leaning press led to a rejection of the proposed constitution. The outlook for the next rewrite—spearheaded by an unelected commission and a smaller elected Constitutional Council—looks bleak.

“This constitutional process is doomed to fail,” says Pablo Seguel, a historian at the University of Santiago, “because the proposed text is much more conservative and regressive than the current constitution of 1980.” The new draft will be put to a vote in December, but Seguel anticipates the center-left and center-right will both reject it. “This is a constitution that belongs to the radical far right,” he says. “Independent from the electoral process that will take place in December 2023, there is a sense of exhaustion across civil society which is dangerous.” After that, a third attempted rewrite is unlikely, Seguel adds. “Most likely amendments to the existing constitution will be made via parliamentary commissions.”

Women’s Rights in the Balance

During his 17-year rule, Pinochet forced ultra-conservative Catholic values upon the country, discouraging women's participation in the labor force and public life and emphasizing their maternal duties. The Chilean Criminal Code, introduced at the end of Pinochet's reign in 1989, prohibited all abortions, even when women's lives were in danger, punishing both those who sought and provided abortions. Feminist organizing pushed the government of former president Michelle Bachelet to relax the abortion law in 2017, allowing access in specific circumstances. But in 2018, President Sebastián Piñera made it possible for clinicians to refuse care on religious grounds, again curtailing access. Currently, despite the restrictions on abortion, the per capita number of abortions in Chile is one of the highest in Latin America.

The current constitutional process, dominated by the far-right Catholic republican movement, promises to roll back Chile’s rigid reproductive rights even further by enshrining protection for “the life of the unborn child and maternity” and banning the morning after pill—a hard won right only achieved in 2001.

The Myth of the Economic Miracle

Until 1973, economic theory and practice in Chile was centred around creating a strong state, protectionism, and inward development. Once Pinochet seized power all efforts were made to shrink the state. Drastic cuts were implemented in public spending and social investment. Industrial production fell by 28 percent in 1975, while GDP was down 12.9 percent. Around 95 percent of public companies were privatized, sold at bargain prices to a handful of buyers linked to the dictatorship.

The 26 Chilean University of Chicago students dubbed the Chicago Boys, mentored by economist Arnold Harberger, prepared a plan called “The Brick” that served as the economic base for the dictatorship. The leader of the Chicago Boys, Sergio de Castro, was named economic minister in 1975, and his associates filled the main positions of power within the dictatorship’s economic team.

When the Latin American debt crisis exploded in 1981, the Chicago Boys did not intervene, causing GDP to fall by 15 percent. Unemployment reached its highest point in 60 years, the Central Bank lost half of its international reserves, and the country sank into the worst recession since the Great Depression. During the remainder of the regime, Chile’s GDP grew just 2.9 percent annually with average annual inflation at 79.9 percent—the second highest of the past 10 governments.

The country handed back to civilian governments in 1990, therefore, was desperately poor and unequal. With a GINI inequality index at 0.57—one of the highest in the world—45 percent of the population lived in poverty and unemployment had risen to 30 percent. Most of Chile’s much-celebrated economic growth took place in the post-Pinochet era, but the promised trickle down never happened. Successive civilian governments did little to modify the model that entrenched deep inequality. The continuation of the system left behind by the regime ultimately produced a breaking point on October 18, 2019, when the country erupted into a yearlong series of nationwide protests demanding rapid social change—and triggering the ongoing constitutional process.

Today, Chile’s employment conditions are so precarious that 50 percent of the workforce cannot accumulate enough savings to fund a minimally adequate pension. Conversely, the armed forces enjoy full pensions, free health care, subsidized housing, and education—a right not granted to the rest of Chilean society. Thirty per cent of labor contracts are short-term and last an average of just 10 months. The country remains one of the most unequal in the developed world with 28.1 percent of total income concentrated among 1 percent of the population.

Human Rights an Urgent Concern

Although President Boric is the first leader since the return to civilian rule to vow to search for Chile’s more than 3,000 disappeared, his government has been unable to address more recent human rights violations. In April, Boric signed into law new legislation, known as Nain-Retamal, that effectively enables police officers to use lethal force in the name of self-defense. The law, formulated by far-right sectors concerned with “security,” was approved by a large majority with only two votes against it. Nain-Retamal also applies retroactively, making it almost impossible for those injured due to disproportionate police force during the 2019 uprising to seek justice or compensation.

At the same time, despite promises to deal with the so-called Mapuche conflict without the use of violence, a state of emergency has been in place in Mapuche territories since the start of Boric’s presidency. The anti-terror law 18.314, enacted in 1984, has been used to arrest Mapuche community leaders, targeting and outlawing the militant Mapuche movement Coordinadora Arauco Malleco (CAM).

“Today, the repression for the Mapuche remains as violent as in the period of the military regime,” says Reynaldo Mariqueo of the Mapuche rights organization Mapuche International Link. “The Wallmapu today is militarized. Raids on communities, arbitrary arrests, and torture continue.”

“Everything seems to indicate that the genocidal policy against the Mapuche people continues invariably today,” Mariqueo adds. “Because it is a state policy that is above the political ideology of the government in power, whose objective is to strip them of their territory and resources, suffocate them economically, and…[eliminate their] national identity.”

Confronting the Past and the Future

Despite the chaos of the constitutional process, the 50th anniversary of the coup takes place amid a flurry of aperture. A delegation of U.S. Democrats that visited Chile vowed to push the Biden administration to apologize for Washington’s involvement in Allende’s ouster and to declassify relevant documents that could illuminate the U.S. role in the coup. Meanwhile, an Ipsos Mori poll conducted at the end of August found that 74 percent of Chileans want a democracy that “ensures that another coup d’état never takes place again.”

“Chile is in post-trauma,” says historian Seguel. “The wounds of the dictatorship have not healed and have not been recognized which has generated a deep division [in society].” Still, glimmers of hope remain amid the darkness of Pinochet’s crushing legacy. “Despite this pain, Chile has a long tradition of parliamentary politics,” Seguel adds. “Diverse political sectors must find common ground to make changes that benefit all Chileans.”

Carole Concha Bell is a PhD candidate at King's College London. She is researching Chilean second-generation diaspora literature and regime discourse at the Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Department (SPLAS). She is also a regular contributor to national and international media on the subject of Chilean politics and Indigenous rights.