This article was originally published by Ojalá.

Leer este artículo en español.

Javier Milei is Argentina’s vernacular representative in the planetary saga of far-right politics. It is enough to see the campaign carried out in his support by Tucker Carlson, Donald Trump’s favorite journalist, and Milei’s bear hug with the Bolsonaro family.

However, there are two issues that give the Argentine franchise of the transnational ultra-right a singular terrain in which to move. On the one hand is the importance of a transversal and mass feminist movement, which is active inside and outside of social and political organizations as well as in the streets and ballot boxes. On the other is an economic crisis marked by the duo of debt and inflation.

These two key aspects of Argentine reality have altered the way the extreme right is expressed. They also play a role in explaining the—at least temporary—relief of having stopped La Libertad Avanza, Milei's coalition, in the first round of general elections after his surprise win in the mandatory PASO primaries on August 13.

Let us return to the singular elements we pointed out above because it is this conjunction that we call politización feminista. Feminist politicization is a way to make visible the crisis in patriarchal models of relating to one another, and to connect it with the deepening economic crisis that has led to increasing income devaluation and the heavy burden of informal work, or work that is formal but underpaid.

When analyzing Massa's forceful and contextual timely comeback, we have to consider the economic desperation of everyday precariousness together with feminist politicization. It is necessary to understand the articulation between the everyday economy and the ways in which the feminist movement has been intervening on multiple levels.

Feminist politicization has been central in dismantling the binary between politics and economics (and the suggestion that one or the other explains Milei's triumph in August and his defeat in October), as well as in suggesting micro-political interpretations of mass phenomena. In recent years, feminist politicization has worked to turn awareness of everyday phenomena and ways of sustaining life in contexts of violence into a quarry of political analysis and articulation with the capacity to intervene.

This has been key in the recomposition of memories that have even altered the narrative of the democratic transition, spinning calendars and moments that have long slept on the shelves of historical marginality. This year Argentina celebrates 40 years of democratic recovery after the popular defeat of the dictatorship, making the possibility of the political triumph of dictatorship deniers all the more disturbing.

During her campaign, Milei's vice-presidential candidate Victoria Villarruel denied state terrorism, whitewashed genocide, and demanded the restoration of compulsory military service. In doing so, she has attacked the popular consensus of human rights struggles, led by the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo (who mobilize for those disappeared during the dictatorship), whose ongoing resistance is a moral north star in Argentina.

We propose to "constellate" a series of points which, from our perspective, have played a fundamental role in Massa’s comeback at the polls, in the same way that the ultra-right thought, with premature triumphalism, that it would win in the first round. We underline the work of political confrontation that activated a battleground in the media, in homes, and on the streets since the August 14 primaries.

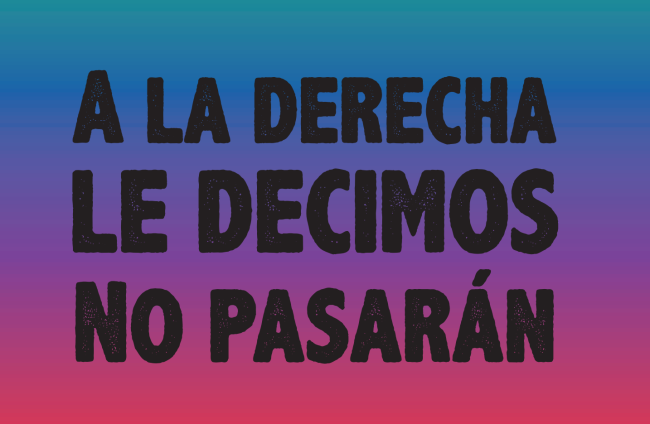

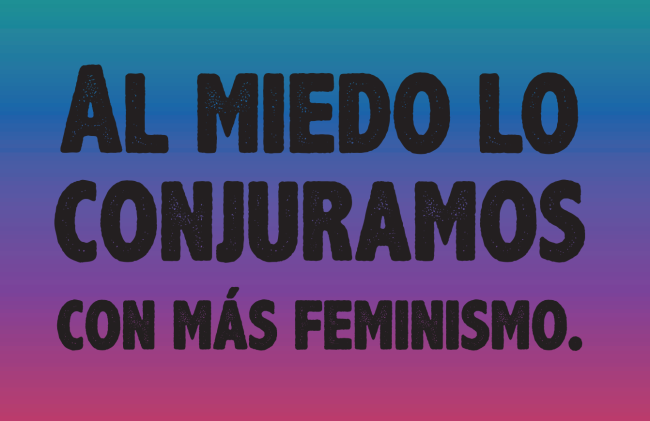

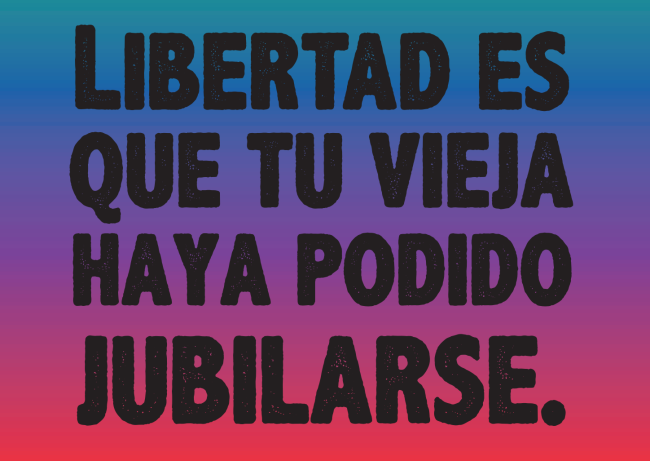

An example of which we were part as the Ni Una Menos Collective is the graphic campaign that illustrates this note. Using slogans that dispute the meaning of the word freedom, we produced together with Mujeres Que No Fueron Tapa (MQNFT) a collective text that associates freedom with rights that make everyday life. Freedom means that thanks to comprehensive sexual education, many children and adolescents have been encouraged to denounce abuse. Freedom means being able to retire after working as a housewife or caregiver thanks to the recognition of care as work.

We are interested in deepening our understanding of how this political activation took place, which through the vote of women and the LGBTQI population (although not not only) activated an emergency brake against the danger of collective destruction. Milei and Villarruel, as well as legislator Lilia Lemoine and Rodrigo Marra, their candidate for head of government in Buenos Aires, have made explicit that danger to an extreme.

Three Feminist Proposals Against the Ultra-Right

How best can we understand the process of activation that rallied votes, took the streets, and burst into the public conversation?

The first element is the proposal of allowing people to carry weapons and the issue of femicides. Milei's proposal was the model of a war of all against all, in order to capitalize on citizen concern about insecurity. However, his suggestion that children go to school with guns, which he expected to ignite like gunpowder, was instead rejected by mothers, generating a great deal of blowback against him.

The issue of weapons has been a cross-cutting concern when it comes to the public debate about femicides. A study by Aldana Romano and Julián Alfie, from the Institute for Comparative Studies in Criminal and Social Sciences (INECIP), found that 97 percent of registered gun users are male, and one in four femicides is committed with firearms. Milei's denial of the existence of femicides in the second round of the debate ignited a sense of alarm among women who, since 2015, have made this issue a central tenet of their organizing.

The response to Milei’s position came from mothers and women across social classes, too many of whom have borne witness to the horror of femicides. This is an example of how the politicization of domestic violence led to results at the ballot box.

The second element is around responsibility for paternity and child support. Lemoine proposed a bill that would "notify" fathers once a woman was pregnant in order to give them the option of acknowledging paternity. This, too, generated a wave of outrage that permeated the conversation in many quarters.

What delicate reflex was activated here? How was it trained by a feminist politicization composed of situated militancy in organizations, discussions, and assemblies but also through public policies?

The process of politicizing motherhood is rooted in the activism of many collectives against non-compliance with child support, which is a de facto way of rejecting paternity. It is also rooted in the struggle against extreme indebtedness of those who work without pay combined with low-paying jobs.

Women go into debt in order to live and to support their families, because of which they become impoverished and are far too busy. Last year, the Ministry of Women, Gender Policies and Sexual Diversity of the Province of Buenos Aires presented an initial measurement that showed shocking data, including that almost seven out of 10 fathers fail to pay child support, or do so in an irregular manner. The National Institute of Statistics and Census has recently begun to incorporate a “Parenting Index,” a measurement of the cost of care work, as a social and legal tool to show how and why poverty is feminized.

This is a vocabulary that comes out of feminist struggle, and which has made more explicit the ways in which precariousness is linked to a moral regime and the gender mandates forced upon women. Questioning why motherhood is penalized with poverty is one way of posing another idea of freedom: the freedom to be a mother without being poor. It is a rejection of patriarchal freedom, which instead allows fathers to take no responsibility for raising and supporting their children.

The third example is connected to care. Milei has denied the gendered wage gap in several public statements. This gendered gap is also evident when it comes to renting a house, getting a job, running a small restaurant or soup kitchen, or taking care of sick family members.

During the pandemic, the amount of care work took on dramatic proportions. This impacted so-called frontline work, but also a range of duties the feminist movement had been drawing attention to for years, allowing for the creation of a new kind of common sense around care work.

A Focus on Microeconomics

We wanted to focus on these issues that, from the analysis of some intellectuals, refer merely to a microeconomics of the doors inside the house. But those doors are no longer closed. The micro is a mode of capillarity that allows us to examine and explain phenomena experienced by millions. When the centrality of the domestic economy—which is where inflation is most keenly felt—is ignored as a sphere of politicization and social conflict, too much information is overlooked.

Of course, it is easier to blame feminism for the frustration of young men in the face of a hostile future. It is easier to blame feminism as well for the resentment of masculinities that are unable to provide a decent livelihood, and to accuse it of trivializing sexual and reproductive rights, as if they were extravagant luxuries.

Feminism has a political capital that is repeatedly rendered invisible. And yet it contains the possibility of activating forms of knowledge that can be translated into concrete struggles.

The images and phrases of collective and democratic freedom, including those reproduced here, are one example of that. These images compete with the financial terrorism of the currency run and the reactionary utopia of armed men.

On November 4, over 1.5 million people attended the 32nd annual Pride March in Buenos Aires. Their slogan was: “¡Ni un ajuste más, ni un derecho menos!” (Not one more adjustment, not one less right).

Milei didn’t win the first round. His numbers were much lower than in the primaries for the reasons we signal above. However, in the week after the general elections, the alliance forged between Milei and former President Mauricio Macri—who took on the debt with the International Monetary Fund in 2018—rearranged the conservative and far right coalition.

Current predictions for the second round of voting are basically a coin toss: the numbers could go either way. For our part, we’ll remain active in the streets, homes, and classrooms to prevent the ultra-neoliberal, negationist, and fascist forces from winning on November 19.

Verónica Gago is a feminist activist, a professor in public universities in Argentina, and an editor.

Luci Cavallero is a feminist activist and researcher. Both are members of the movement Ni Una Menos.