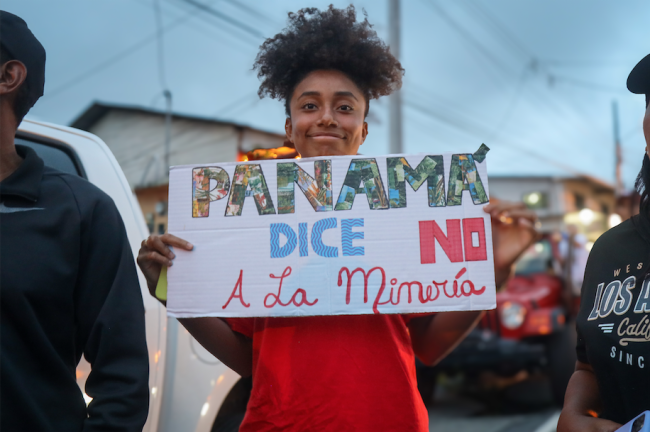

On November 28, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled a new contract with the Canadian firm operating Central America’s largest open-pit copper mine to be unconstitutional. Panamanians celebrated outside the Supreme Court building, cheering and waving the Panamanian flag. The ruling offered some closure to more than a month of street protests and roadblocks that had shut down major portions of the country. In several states, propane and gas ran out, and many supermarket shelves were left empty. Organized by unions, teachers, students, and Indigenous movements, the protests were the largest the country had seen in decades. Those in the streets said they would not stop until the mining contract was revoked.

The protests engulfed the country on October 23, after Congress fast-tracked the approval of a new contract and President Laurentino Cortizo quickly signed it into law. Government officials and allies said the contract would bring Panama windfall profits. The mine, run by the Canadian corporation First Quantum, has extracted roughly 300,000 tons of copper a year since beginning commercial operations in 2019, which accounts for roughly 5 percent of Panama’s GDP. Under a previous contract with the government, First Quantum paid the state $35 million a year in royalties for the right to mine. Under the new 20-year contract, that figure was increased 10-fold. But the demonstrators who took to the streets said the contract was a handout to a major foreign corporation—a slap in the face that would threaten Panamanian sovereignty, destroy the environment, and pollute Panamanian rivers in a time of drought.

In the days after the Supreme Court decision, I spoke with Central America Studies scholar and NACLA Editorial Committee member Jorge Cuéllar about the impact the huge anti-mining protests and the court ruling could have abroad. Cuellar is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies at Dartmouth College. He has written often about popular struggles and mass movements in Panama and across Central America. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Michael Fox: What kind of an impact do you think this ruling could have for foreign companies doing business in Panama and particularly in areas like mining?

Jorge Cuéllar: For me, the court ruling against the copper mine sets a precedent that foreign companies can't come into places like Panama that have been historically friendly to transnational capital, and extractive capital specifically, and do what they want with the state. Because people have stepped in to curb some of the most extreme excesses of this extractive industry.

For Panama, which considers itself a kind of natural patrimony for the world that offers a kind of eco-friendly experience—eco-tourism, natural beauty, and very unique biomes—this mine really was antithetical to that vision and that national identity that Panamanians themselves have taken up and become very proud of. The mine really stood against that vision.

And so, when foreign companies come in and try to extract copper that is going to get shipped elsewhere like China and the Near East, where it'll be processed, a lot of the capital and value generated from that raw material is not going to come back to Panama. That is not perceived to be a good deal for Panamanians.

The protest that shut down the Pan-American Highway was precisely about this: that companies are taking advantage of lax rules. And they're not leaving anything positive for Panamanians. This is a generational argument that that social movements are making because mining very much represents a short-term interest. It’s something that might generate employment and capital in the near term. But what about the irreparable destruction of the natural environment? This is the contradiction that social movements have pointed out and that they won’t stand for it any longer.

So businesses and foreign companies can no longer assume that countries like Panama, which has been famous for doing some of the most egregious forms of money laundering for capitalists and elites, is not open for this kind of business any longer.

And I hope that this ruling holds so that no more exploratory mines are opened in Panama and that the will of the people becomes enduring law.

MF: Do you think this ruling is sending a message to foreign investors?

JC: This is sending a very clear message to foreign investors. There was an article in The Financial Times that was talking about the investment climate and the various gradings that entities like JP Morgan and Moody’s offer investors to describe the positive or negative climate for investment and these kinds of extractive projects in the Global South. And Panama's rating was recently downgraded because of this.

But indeed it is sending a message to foreign investment and to particular kinds of foreign investment. These kinds of extractive capitalists are very used to extracting and making value in other places and hoarding the wealth generated from that extraction in the coffers of the Global North—in Europe and the United States and other places that are not Panama, that are not El Salvador, that are not Honduras.

There's a pattern here that the people have simply said “enough is enough” in terms of not accepting this kind of foreign investment. If this is the kind of foreign investment that politicians and capitalists are innovating in 2023, then Panamanians want no part of it. And I think that is a clear message that is being sent to foreign investors, to the Panamanian state, and to other states in the region where extractive capitalists and extractive operations have seriously destroyed the life-worlds, the ways of living, the communities, and the ancestral territories of many, many, many people.

No longer is this an acceptable condition of being.

MF: What else is significant about the victory of this struggle in a regional perspective?

The other thing that is really clear, and that goes alongside other trends in Central America, is that land defenders, environmental protectors, and water protectors, are becoming quite active and effective in catalyzing and crystallizing general disaffection and discontent by different national publics.

So, in Panama, teachers, Indigenous groups, truck drivers, students, and many, many different sectors of society came together to make clear to governing bodies that the mining project is not for everyone. The mining project is a very sectorized, limited form of development that has no place in Panama.

In El Salvador, since 2017, there has been a metallic mining ban that was hard won by water protectors in places like Tacuba and Cabañas. All over El Salvador communities are again mobilizing against mining, a pernicious form of development that is antiquated, that is violent, that is destructive, that is damaging. And that is not with the times of environmental conservation and imagining the future of these countries beyond the short-termism of electoral cycles and extractive time.

And what I mean by extractive time is that when these mining projects are done, when they've been tapped out, the companies move on and what's left is a hole in the earth. Wildlife and communities are left with the destruction and an open pit that is useless—that does nothing, that doesn't provide life, that doesn't allow for folks to make a living any longer.

I think it's that short-termism that is being called into question throughout the region.

These are very much fragile victories and we'll see where this goes. But if the Salvadoran context is any indication with current president Nayib Bukele, this is something that's being brought to the table again in the sense that the state wants to overturn the metallic metals mining ban.

MF: What do you think is one of the most important lessons from this anti-mining struggle and Supreme Court ruling?

JC: There is another way and there is another path. And what this means is to bring the sectors that were protesting and putting up blockades all over Panama to the table in order to imagine and innovate, devise and co-create what Panama's economic future is going to be. That will be impossible if the political class is unwilling to integrate these views into governance, into policy design. But the Panamanian people will not just roll over.

This was one of the most important lessons of this moment, that the Panamanian people will not just accept this contract and take it lying down. In fact, they stood up and forced the institutions and government to pay attention to them and to heed their needs.

MF: Do you think this victory in defense of the environment could inspire other movements in other countries to stand up to megaprojects like mines elsewhere?

JC: Indeed the Panamanian victory over first Quantum Minerals does send a message to other social movements that are already animated around environmental and land defense and territorial struggles, not only in Central America but also in South America, Africa, and other places. The lesson from the social movements and people of Panama is going to inspire and galvanize other movements to take a stand against this gargantuan beast of extractive capital and to push back against the politicians that are very much in line and in bed with extractive interests.

I believe these events are also going to affect the Panamanian elections coming up in 2024 and also have ripple effects throughout the region. The fact that Panama is seen as the most developed nation of Central America will have a certain kind of symbolism to other territorial and environmental struggles in the region, especially in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, where there’s a push against mining as well. Struggles against hydroelectric development and the damming of rivers, and other forms of underground and extractive mining will also be motivated and in some ways supported by what the Panamanians have achieved and how their politics of protest brought so many different sectors together to make the state react and respond in in a positive and affirmative way. That is it is an important model for other movements in the region that oftentimes feel like they're in an isolated battle with these massive transnational corporations.

The outcome of the protests also goes to show that there is still a modicum, a morsel, a fragment of democratic possibility through state functions—in this case Panama's government and Supreme Court—that can be moved to call these things unconstitutional, to create new laws that overturn extractive concessions, and to once in a while do something positive for the well-being of ordinary people.

Politics as usual, that leaves out popular needs and popular interests, is acceptable no longer. This is a long arc, from the Panama Papers through Covid into the present. And the mining industry is one of the most egregious and extreme and repeat offenders of attacks against the livelihoods of ordinary people, whether they are Afrodescendant, mestizos, Indigenous people. Extractive capitalism doesn't meet their needs and doesn't provide them with positive returns in the same way that it does for the mining sector and the political elite that benefit from extractivism.

So this is an important decision by the Panamanian courts and by the people primarily who are laying down an important template and model of how to push out these predatory capitalist interests.

Michael Fox is a Latin America-based multimedia journalist and host of the podcast Brazil on Fire. He is currently in Panama, where he has been covering the protests since October. He was previously editor of NACLA. He tweets at @mfox_us.