This piece appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

“Could you please report this tweet! And if you have the space[,] share with others in your trusted circle of friends to do the same?” I received this text message after the Dominican ultranationalist group Antigua Orden Dominicana posted a tweet outing a queer couple in the country. Over the past decade I have become accustomed to these kinds of requests for support aft er ultranationalist groups catch wind of an individual known for their activism “in support of Haitians” or “espousing gender ideology.” The comments on the offending posts quickly become littered with death threats, racist and xenophobic epithets, and accusations of treason. Often, those who face surveillance and repression due to being identified through traditional and social media are racialized Black women and femmes.

The Antigua Orden Dominicana (AOD) is an ultraright-wing, neofascist paramilitary group whose goal is to protect the Dominican Republic “at all costs.” Members of the movement don black combat boots and black military-style uniforms emblazoned on the arm with the Dominican flag and the words “Dios, Patria, Libertad,” (God, Country, Liberty). On Facebook, where AOD has more than 77,000 followers, the group has described itself as a nationalist movement “created for the expulsion of Haitians from Dominican towns and cities.” Over the past decade, AOD members—often while the Dominican national police look away—have regularly disrupted marches and vigils organized by feminist and antiracist groups to denounce human rights violations against Black Haitian migrants and dark-skinned Black Dominicans, women, and LGBTQIA+ communities. Most recently, in October 2023, AOD members threatened and harrassed participants at a vigil in Santo Domingo in solidarity with Palestinians.

Although AOD’s anti-Haitian, anti-Black, and homophobic intimidation tactics might at first appear to be the work of a fringe group, the paramilitary movement is in fact part of a larger historical and regional pattern of right-wing state and non-state violence, censorship, and threats against Black women and migrants over the past century. In recent decades, the Dominican Republic has seen a retrenchment of right-wing, fascist movements that increasingly depend on the solidification of neofascist paramilitary groups. While paramilitary groups were present during previous right-wing regimes and dictatorships, their presence today points to the new contours that shape repression against anyone deemed a threat to Dominican sovereignty.

As the Dominican Republic gears up for the 2024 presidential elections, the scapegoating of Haiti, Haitian migrants, and their descendants is expected to rise. Most recently, these disruptions have extended into educational spaces, where concerns about a bilingual children’s book written in Spanish and Haitian Kreyòl, as well as false narratives about erotic poetry being taught to children, have become lightning rods for the right wing to call for the banning of books and the firing of Black feminist educators. As Black, queer, feminist, and antiracist movements mobilize to denounce state and non-state violence, the number of threats and disruptions from right-wing groups such as AOD will only continue.

Black Dolls, Black Stories

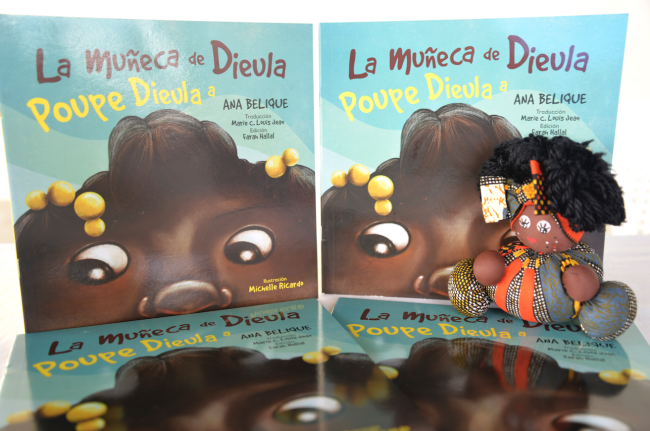

In 2021, Ana María Belique, a Black Dominican woman of Haitian descent, published the bilingual children’s book La muñeca de Dieula, Poupe Dieula. The book, which tells the story of a girl whose mother sews her a Black doll, was part of larger project to enable Black women and girls to see themselves reflected in popular culture. In 2019, Belique and other members of the antiracist movement Reconoci.do launched Muñecas Negras RD, an initiative that creates Black dolls as a way to build intimate spaces of recognition while generating income for marginalized women. It was the beginning of what Belique dubbed pensamiento crítico bateyero, a Black feminist thought and praxis born out of the experiences of Black Dominican women and girls of Haitian descent from sugar cane communities known as the batey.

Women designers living in bateyes—who often face limited work opportunities due to the denial of citizenship to Dominicans of Haitian descent—carefully crafted each doll using locally purchased cloth, thread, and yarn (for the hair). While the first batch was primarily purchased by people living outside of the Dominican Republic, the next generation of dolls were gifted to children within the creators’ own community and sold in Dominican feminist spaces.

Muñecas Negras RD has provided a space for Black Dominican women of Haitian descent to speak about their experiences with gender and racial discrimination. As one of the founders, Maribel Pierre explained, “People think that when they call you Black they are offending you, not knowing that when they call you Black they are reminding you where you are from, who you are, who your ancestors are.” These sentiments, shared by many creators who participated in the making of the dolls, were the impetus for Belique to write La muñeca de Dieula. The story is inspired by one of the young girls of the batey who would often stand by the window to peak in and see what the older girls and women were crafting and discussing.

After the book’s release, Belique and the book’s illustrator and publisher, Michelle Ricardo of Proyecto AntiCanon, were set to present at the 2022 International Book Fair in Santo Domingo. On social media, AOD and its ultranationalist supporters soon began heralding Belique’s book as a sign of the Haitianization of Dominican society. They warned that the book was being read in public schools and teaching children Haitian Kreyòl. They also directly threatened Belique and Ricardo and called for the boycott of the book presentation at the fair, which led to the cancellation of the event. Instead, Ricardo read a poem about the intimidation and threats, which led to further intimidation and threats on social media.

The Rise of Neofascist Groups—and Their Repression

Groups such as AOD argue that the Dominican Republic is a sovereign nation that has a right to defend itself from accusations of human rights violations such as racism, xenophobia, homophobia, or misogyny. In addition to the recent assault on Palestine solidarity demonstrators and backlash against La muñeca de Dieula, far-right groups have repeatedly leveled threats and aggression against human rights defenders, disrupting events including rallies denouncing statelessness, artistic anticolonial performances, human rights commission hearings, and a vigil after the police murder of George Floyd in the United States. While the majority of these events took place in Santo Domingo, far-right groups and individuals have also disrupted educational panels held in New York City, where AOD has a presence.

These kinds of self-identified nationalist disruptions have been on the rise over the past decade. Amaury Rodríguez, a Dominican author and translator whose work highlights Dominican, Caribbean, and Latin American history from below, notes: “The use of repressive forces to squash social protest has become commonplace.” The presence of neofascist paramilitary groups is part of the new contours shaping the repression against anyone deemed a threat to Dominican values. For the human rights activists documenting how threats that emerge in the virtual world spill into physical spaces, the proliferation of nationalist and fascist groups on social media platforms such as Facebook has become increasingly concerning.

In December 2016, at an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights session in Panama City, several Dominican human rights organizations provided a report on the increasing threats of violence against human rights defenders, in particular members of social movements and organizations speaking out against racist and xenophobic government policies. The report detailed how right-wing, self-identified nationalist groups were creating videos and posts online that sought to expose what they referred to as anti-Dominican propaganda. Members of the Dominican civil society delegation listed a series of intimidation tactics, which they put in the context of a long history of threats and physical violence experienced by human rights defenders in the country. They also noted that they had documented and shared their concerns with Dominican authorities, who had not responded to their reports. Since then, at least one of the members of the delegation left the country over concerns for herself and her family.

Civil society groups have continued to call attention to unchecked far-right violence. In October 2022, participants in the jornada anticolonial suffered physical aggression at the hands of AOD, which had called on its members to disrupt the event. For nearly two decades, various social organizations have participated in a series of events each October to denounce national celebrations that glorify Christopher Columbus, colonization, and slavery. In a press conference after the incident, civil society organizations called on President Luis Abinader to demand that groups such as AOD halt their threats and physical aggressions. Despite formal complaints submitted to the prosecutor’s office, there have been no formal investigations or responses from the state.

Read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time.

Amarilys Estrella is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Faculty Affiliate of the Center for African and African American Studies at Rice University. She is also a founding member of the collective We Are All Dominican.