This piece appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

and it was Beirut all over again

with the sky expanding

every section to make

room for the anonymous

heroes of the streets of

El Salvador.

– Etel Adnan

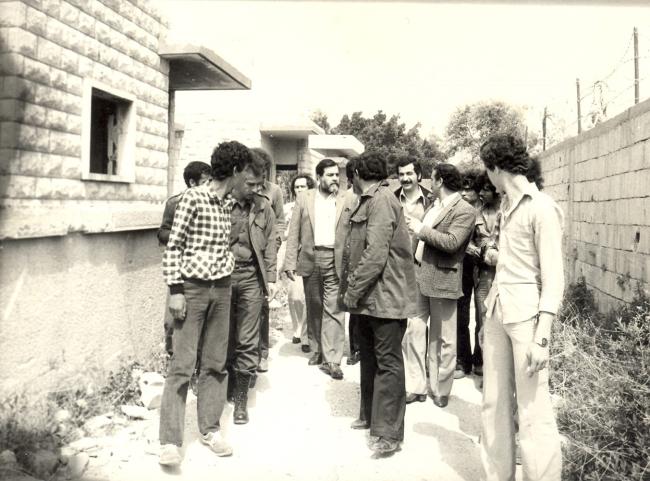

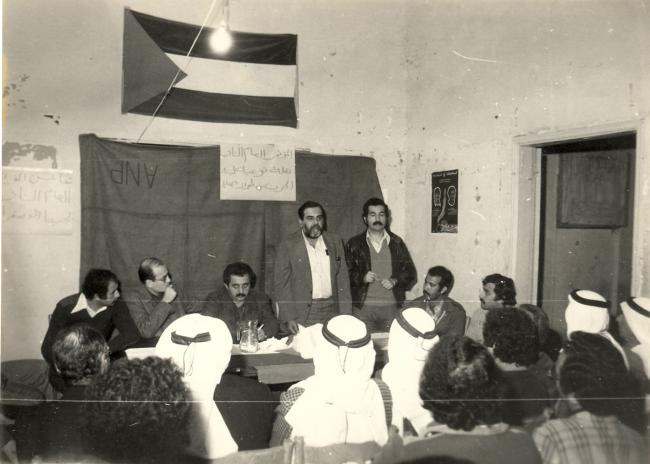

On March 24, 1981, Schafik Handal, the secretary general of El Salvador’s Communist Party and the international representative of the militant Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), delivered a press conference in Beirut. Condemning “U.S. imperialism” and the role of “Israeli experts” in his country’s growing armed conflict, he spoke of the shared aspirations of the resistance in El Salvador and those in Lebanon, Palestine, and the Middle East more broadly. The event capped off his first visit to the Middle East, a week-long diplomatic mission aimed at fostering closer relations with leftists in the region.

Shortly before the trip, the newly formed FMLN guerilla coalition, of which Handal was a founding member, had suffered strategic setbacks following an escalation in armed resistance against El Salvador’s U.S.-backed authoritarian government. Meanwhile, in Lebanon, the revolutionary left was also embroiled in civil conflict that gradually eroded their strength and influence. Within this context of war and momentary failures, Handal traveled to Lebanon to build inter-regional networks of support. As the son of Palestinian migrants, Handal also had a personal connection to his Middle Eastern comrades. Although he needed a Spanish-to-Arabic translator during his trip, he emphasized his Palestinian heritage and the common circumstances that tied Latin America to the Middle East. In particular, Handal stressed that these two regions had a common threat: the alliance of U.S. and Israeli arms, funds, and military training.

This mutual threat only increased in 1981 as U.S. President Ronald Reagan took office with an aggressively anti-communist platform and a commitment to upholding right-wing governance in Latin America and the Middle East. Reagan had expressed his support for the Lebanese right-wing Christian militia headed by Bashir Gemayel and was simultaneously engaged in countering leftist guerilla forces across Central America. As such, the Reagan administration viewed Handal’s movements as particularly dangerous, interpreting further Middle East-Latin American revolutionary collaboration as a direct threat to U.S. policy.

The State Department surveilled Handal’s visit to Beirut with particular concern for his meetings with Yasser Arafat and other members of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) based in Beirut at the time. This surveillance only increased after Arafat declared: “We have connections with all revolutionary movements throughout the world, in Salvador, in Nicaragua—and I reiterate Salvador.” In memos and correspondence, U.S. officials and their Israeli allies identified the danger this connection posed to interregional security and emphasized Handal’s Palestinian heritage to incite fears of transnational “terrorism” in the twilight of the Cold War.

As Handal’s first time in the Middle East, this visit was a kind of return for a Palestinian-descendant Salvadoran whose father and mother once called the Eastern Mediterranean their home. But his task at hand was guided more by political urgency than nostalgic reflection. His primary purpose was to build networks of solidarity across movements under threat. Although they all waged different wars, they shared the same adversaries. While Handal’s heritage was important to his interactions with the PLO and Lebanese revolutionary parties, he focused on how resistance between Latin America and the Middle East was connected through a common struggle against the oppression meted out by the hegemonic alliance of U.S. and Israeli financial, material, and diplomatic interests. It was a position he held throughout his life, even as it put him ideologically at odds with other Palestinian Salvadorans in politics such as conservative Antonio “Tony” Saca, to whom Handal lost the Salvadoran presidential election in 2004.

Handal’s legacy modeled a mode of solidarity that acknowledged the importance of common identity while emphasizing other equally urgent nodes of connection. As the U.S. government tried to associate his radical politics with his Palestinianness, Handal insisted that the bond between him and his Middle Eastern counterparts was rooted more in the shared experience of U.S.- Israeli violence than in cross-continental Arab identity. Handal’s precedent of solidarity offers a powerful counterpoint to current conditions in El Salvador as Palestinian-descendant president Nayib Bukele seeks to court favor from an Israeli state that not only destabilized the country in the past but also facilitates aspects of his authoritarian rule today. Handal is a specter that haunts this contemporary politics with the reminder that Palestinian solidarity and resistance across continents is not just affective—it is a commitment to challenging the conditions and forces of oppression wherever they exist.

The Handals from Palestine to El Salvador

The Handal family was one of the largest and most prominent Christian Orthodox families in Bethlehem. Based in the oldest quarter of the city in Harat al-Najajreh, they worked in different industries but were known for being traders and actively involved in the Palestinian philanthropic scene through the early 20th century. Schafik’s parents Giries and Giamile Handal left in the 1920s when Zionist settlers started to foment unrest. They ultimately settled in El Salvador, where other members of the family had emigrated during earlier movements of migration to the region.

Giries Abdala Handal became Jorge Hándal when he first migrated to El Salvador in 1920. He returned to Bethlehem in 1928 and married Giamile, who later became Erlinda Hándal, and he and his new wife permanently settled in El Salvador in 1929. Giries worked for the Hándal family business in Usulután, selling various hardware goods in the ferreteria in the town center. A year later, in 1930, Shafik was born, the first of six children. Later that decade, the Hándal family relocated to the capital city of San Salvador.

This was a particularly difficult time for the Palestinian community in El Salvador as they faced a series of discriminatory legal and bureaucratic changes targeting foreigners generally and Middle Eastern migrants specifically. Among these measures was the Foreigner Law of 1929, later developed into the Migration Law of 1933, which explicitly prohibited Arab migration. At the root of these laws was a xenophobic panic over foreign “others” that sought to both restrict migration and limit the growing success of these communities. Similar laws restricting Middle Eastern migration were implemented in neighboring countries such as Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua.

During this period, Palestinians who had taken up residence in El Salvador were required to register yearly with the Department of Migration. Even Palestinian descendants born in El Salvador were forced to provide the registry with biographical information, including where they lived, if they could speak Spanish, and who among the local population could vouch for them. In 1936, under the repressive dictatorship of Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, the Salvadoran government introduced additional restrictions. Decree No. 49 prohibited individuals of “Arab, Palestinian, Turkish, Chinese, Lebanese, Syrian, Egyptian, Persian, Hindu, and Armenian races” from opening new businesses, partnering with other business owners, or expanding their existing enterprises, even if they were naturalized Salvadoran citizens.

Against this backdrop, the notion of the “undesirable” or pernicious foreigner took root in Salvadoran national discourse, part of a broader hemispheric phenomenon from North to South America. While this attitude was not exclusively applied to Palestinians, migrants from the Middle East were particularly singled out in El Salvador due to their economic success. Throughout the late 1920s and the 1930s, Palestinian trade networks, business operations, and supply chains were characterized as dishonest or manipulative and frequently represented in the press as a threat to Salvadoran production and commerce.

Despite—or perhaps because of—these circumstances, Giries and Giamile’s children became political activists deeply involved in Salvadoran social and political movements during the 1940s. Schafik and Farid, in particular, became prominent figures in the country’s leftist organizations, political parties, and causes. At 14 years old, Schafik was part of the effort to organize a nationwide strike against the Martínez dictatorship, and by 18, he was the leader of both the Democratic Students Association and the Revolutionary Students Committee at the Universidad de El Salvador. He joined the Communist Party of El Salvador in 1950 and rose through the ranks to become secretary general in 1973.

From that decade onward, Handal became one of the most important figures of the Salvadoran left. Throughout the 1970s, he was crucial to electoral coalition-building during several waves of violent state repression. But more importantly, he was central to the formation in 1980 of the FMLN, a coalition of leftist groups engaged in armed resistance against the repressive U.S.-backed government and allied paramilitary death squads. The FMLN formed in response to the spread of state violence against civilians, workers, clergy, peasants, students, and other groups who were critical of the state-sponsored human rights violations and militarization that ultimately sparked a 12-year-long civil war. It was during this time, primarily through Handal’s work, that the FMLN established ties with global resistance movements—particularly Palestinian resistance—in the fight for collective liberation.

The United States and Israel in the Salvadoran Civil War

The armed conflict that engulfed El Salvador from 1980 to 1992 claimed over 75,000 lives and displaced approximately 1.5 million people. According to the UN-backed Truth Commission, 85 percent of the more than 22,000 incidents of political violence committed during the war were attributed to parties acting on state orders, including soldiers, paramilitaries, and death squads. The Salvadoran military was responsible for 60 percent of political violence, whereas the FMLN was to blame for 5 percent. Instances of violence documented in the Truth Commission report included mass executions, massacres, targeted assassinations, enforced disappearances and kidnappings, torture, sexual violence, and other abuses.

By the start of the civil war, El Salvador’s military rulers had been wielding political violence to suppress popular uprisings and anti-government activities for decades. The most egregious example was the 1932 massacre in eastern El Salvador of some 30,000 people, mostly Pipil peasants, who rebelled against the Martínez regime. The 1980s, however, brought unprecedented levels of U.S. and Israeli support for the Salvadoran government’s repressive activities. In the name of curtailing the spread of communism, the Reagan administration funded, supplied, and trained right-wing counterrevolutionary forces across Central America and diplomatically supported El Salvador’s military and government as it targeted civilians and the leftist FMLN insurgency. The United States provided El Salvador with over $1 billion in military assistance over the course of the war, even as the military and its affiliates committed atrocities. Most infamously, in 1981, the U.S.-trained Atlácatl Battalion killed nearly 1,000 civilians, over half of them children, at El Mozote, which remains the deadliest massacre in modern Latin American history.

But it was not just the United States facilitating this right-wing violence. As the Iran-Contra Affair would later reveal, Israel was a central player in the U.S.-sponsored scheme to equip the Contras in Nicaragua, and it had a similarly key role in supporting other counter-insurgent campaigns and authoritarian regimes across Latin America during the Cold War. At the height of state terror in Latin America in the 1980s, Israel was a leading supplier of arms in the region, second only to the United States, and also lent its tactical expertise. According to Al Jazeera, since its formation as a state in 1948, Israel has armed, trained, and advised over a dozen Latin American countries including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela.

In the case of El Salvador, Israeli intervention pre-dated the civil war, providing arms and training to a series of military-dominated regimes that came to power in the 1970s through fraudulent elections. From 1975 to 1979, Israel accounted for 83 percent of the country’s military imports. Israel’s involvement, encouraged and aided by the United States, continued into the 1980s with disastrous outcomes. Among the recipients of Israeli arms and training was the notorious National Security Agency of El Salvador (ANSESAL), the secret police force that formed the nucleus of the death squads that killed thousands of Salvadoran civilians. Israel’s impact can even be traced to the symbolic start of the war, as Roberto D’Aubuisson, the military officer who ordered the 1980 assassination of El Salvador’s outspoken archbishop Óscar Romero, received both U.S. and Israeli training.

Read the rest of this article, freely available for a limited time.

Amy Fallas is a Salvadoran-Costa Rican writer, editor, and historian. She is an assistant editor at the Arab Studies Journal and a PhD candidate in history at the University of California, Santa Barbara.