May 3 was a surreal day at the Tucson Unified School District (TUSD). That afternoon, the entire neighborhood surrounding the district’s headquarters was blocked off by Tucson police officers. K-9 units were on the prowl for bombs, snipers were stationed on the building’s roof, a bomb squad patrolled the front of the building, and a helicopter hovered above. Dozens of officers lined the streets, and there were police vehicles as far as the eye could see. Near the entrance stood a makeshift altar set up by local clergy. By 4:30 p.m., two hours before the start of the school board meeting, several hundred people gathered outside, in the 90-degree desert heat. The building was locked down. Why this high level of “security” usually associated with militarized societies?

One week earlier, nine students had chained themselves to chairs at the April 26 TUSD board meeting in an act of civil disobedience in protest of the banning of Mexican American Studies. On December 30, 2010, Arizona State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne declared the school district’s Mexican American Studies program out of compliance with A.R.S. § 15-112 (introduced as HB 2281)—a law enacted in May 2010 that effectively banned the teaching of ethnic studies in Arizona’s K–12 schools and primarily targeted TUSD Mexican American Studies.1 Rather than wait for Horne to destroy the highly successful Mexican American Studies program, the TUSD School Board began dismantling it internally by removing Mexican American Studies classes from core curricula and demoting them to elective status.2

One week earlier, nine students had chained themselves to chairs at the April 26 TUSD board meeting in an act of civil disobedience in protest of the banning of Mexican American Studies. On December 30, 2010, Arizona State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne declared the school district’s Mexican American Studies program out of compliance with A.R.S. § 15-112 (introduced as HB 2281)—a law enacted in May 2010 that effectively banned the teaching of ethnic studies in Arizona’s K–12 schools and primarily targeted TUSD Mexican American Studies.1 Rather than wait for Horne to destroy the highly successful Mexican American Studies program, the TUSD School Board began dismantling it internally by removing Mexican American Studies classes from core curricula and demoting them to elective status.2

This led to the April 26 action. The board reacted by militarizing the next meeting with as much security as possible, claiming it was for the safety of the students and community members. Loudspeakers were put on the rooftop for the hundreds of people outside, since it is against boardroom policy to prevent the community from hearing the meeting’s agenda. As each minute passed, more supporters of Mexican American Studies arrived; a troupe of nearly 50 people showed up on bicycles with megaphones and flags. At the TUSD entrance, dozens of officers frisked and scanned everyone who entered with metal-detecting wands. Inside, many more heavily armed officers roamed the sealed-off building. Shortly before the meeting commenced, a number of officers in riot gear marched up the aisle in the boardroom. At least 50 officers were inside the building. Perhaps 150 were outside (estimates vary).

The board members sat in their designated chairs, waiting attentively to convene the meeting and seemingly oblivious to the unprecedented militarization surrounding them. After the meeting began, District Superintendent John Pedicone recommended tabling the proposal that would make Mexican American Studies classes electives (establishing a path to elimination), but it was never clear whether the board would follow this recommendation. TUSD’s usual 30-minute “call to audience” portion began the meeting, allowing select individuals to speak for three minutes each. The last speaker, Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith, a respected professor and community activist, reminded the board that no matter how much they tried to dismantle Mexican American Studies, the community of Tucson would exist well beyond their tenure and the collective fight would continue.

After a rousing standing ovation, there was a motion from the floor for additional time to speak. The motion was denied, but an audience member boldly stood up and approached the podium. She was promptly arrested and escorted out by eight security officers. A second audience member, Lupe Castillo, a 69-year-old disabled woman, began to read Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s, “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.” Several officers in full riot gear approached her from behind, escorted her out, and arrested her. There was bedlam. About a dozen students took off their sweatshirts and, with fists in the air, revealed their T-shirts, which read: “You can silence our voices, but never our spirits.” Amid chaos, riot police threw several elderly people and a cameraman out of the building. After Castillo was escorted out, five others were arrested for speaking. After much community outcry, the board finally adjourned the meeting and tabled the proposal, but not before many Mexican American Studies supporters and students were assaulted outside by Tucson police officers.3 With the proposal tabled, Mexican American Studies was left intact after the May 3 meeting.

*

The struggle for equitable, relevant education through Mexican American Studies has been occurring for years. Since 2006, TUSD’s Mexican American Studies program has come under political attack on a statewide level, in particular from Tom Horne. From 2006 to 2010, Horne wrote three separate pieces of legislation to eliminate Mexican American Studies in TUSD. In the summer of 2009, hundreds of community members ran from Tucson to Phoenix in 115-degree heat as a visible social protest meant to raise awareness and ultimately defeat the proposed anti-Mexican American Studies law. As Horne continued his campaign, the students in the district responded with a series of meetings, protests, marches, rallies, vigils, and more runs. All of this changed in 2010, when growing fears around immigration, a recession, and a midterm election made Mexican American Studies a perfect wedge issue to feed the Arizona Republican base. The proposed legislation did not stand alone. The draconian SB 1070 (legalizing racial profiling) and Prop 107 (banning affirmative action) were also introduced by Arizona Republicans during this election cycle.

When Horne introduced HB 2281, he reminded the public that he had participated in the 1963 March on Washington. Invoking Dr. King, Horne attacked Mexican American Studies as antithetical to “the Dream,” in an obvious attempt to avoid being labeled a racist. The law mandates that a school district can lose 10% of its state funding (about $15 million) if curricula violate any of the following criteria: that classes (1) advocate ethnic solidarity rather than treating pupils as individuals, (2) promote resentment toward a race or class of people, (3) are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group, and (4) promote the overthrow of the U.S. government.4

These provisions were problematic for a number of reasons. The first tenet (ethnic solidarity) has almost no tangible meaning. What does ethnic solidarity look like? The vagueness allows Horne to misinterpret and misuse the term la raza, equating it with ethnic chauvinism (“the race”) as opposed to ethnic pride (“the people”).5 There is a certain irony in Horne citing Dr. King and the March on Washington, a race-based collective, as a way of framing ethnic solidarity as inherently negative. The second tenet (promoting racial resentment) is an attack on even teaching about racism because this contradicts Horne’s view that students should be “taught that this is the land of opportunity, and that if they work hard, they can achieve their goals. They should not be taught that they are oppressed.”6 Horne rejects the notion that racism still exists and equates the teaching of racism with victimizing white people. This fits well within contemporary racial theory whereby racism is so systemically ingrained in society that color-blindness actually becomes a form of racism.7

With respect to the charge of ethnic grouping, one could argue that the disproportionate representation of white students in advanced-placement high school courses means they are designed for a particular ethnic group. However, these classes will never be the targets of HB 2281, since Horne only finds ethnic clustering problematic when minorities do it. Finally, the tenet about overthrowing the U.S. government relies on a racist framing of Latinas and Latinos as foreign “others” worthy of increased scrutiny and suspicion.8 Sedition is an extremely serious charge, and the inclusion of this criterion in HB 2281 plays to the popular racist view that Latinas and Latinos are not fully American, that their national loyalty is in question, and that they might even try to reconquer Aztlán—the name given by Chicano activists to the territories seized in the Mexican-American War (1846–48).

On May 11, 2010, Arizona governor Jan Brewer signed HB 2281 into law after it was approved by a margin of 32 to 26, and it eventually became A.R.S. § 15-112. The next day, Horne came to Tucson for a victory lap.9 He had planned to hold a press conference at the TUSD headquarters to announce the bill’s passage. However, middle and high school students formed a human chain around the building, and Horne retreated to the Arizona federal building in downtown Tucson. Several hundred students followed him there, filled the building, and waited to address him after the press conference. Instead, Horne left through the rear entrance, avoiding the community at all costs. In the end, 15 people were arrested at the federal building for refusing to leave until they could meet with Horne.

During his time as state superintendent, Horne never set foot in a Mexican American Studies classroom or conducted a systematic audit of the program. He said that if he did attend a class, it would likely be tailored to avoid controversial subjects in his presence.10 On his last day in office, Horne found TUSD out of compliance on all four tenets of A.R.S. § 15-112, arguing, “In view of the long history regarding that program, the violations are deeply rooted in the program itself, and partial adjustments will not constitute compliance.”11 In other words, there was no way for the Mexican American Studies program to meet the state requirements; it could only be eliminated.

Although Horne became the Arizona attorney general before he could fully enforce A.R.S. § 15-112, his successor, John Huppenthal, has carried the torch. This was not surprising, since Huppenthal’s campaign advertisements specifically said that if elected he would “stop la raza.”12 He did not say he would stop Mexican American Studies, ethnic studies, or raza studies. Rather, he would stop la raza—that is, the people of Mexican descent in Arizona.

*

The TUSD school board capitulated to the pressure applied by Huppenthal and the school district under A.R.S. § 15-112. First, the board voted not to challenge the constitutionality of the law.13 Second, board president Mark Stegeman introduced what has become known as the Stegeman Resolution.14 The resolution was couched in the language of valuing diversity—“The traditional high school core curriculum substantially ignores the experiences and contributions of ethnic minorities,” it reads—yet it demoted Mexican American Studies courses from being part of the core curricula to electives, slowly bleeding the program from the inside out. On top of students’ already packed schedules, taking an additional elective literature or history course would be overbearing. Although this proposal made no sense to the students, Stegeman insisted he knew best.

Disregarding vocal, consistent community opposition, Stegeman introduced his resolution for a vote at the April 26 board meeting. Most board members, including Stegeman, believed he had the necessary votes to pass his resolution.15 For many in the community, the vote seemed to be a foregone conclusion and the dismantling of Mexican American Studies seemed imminent. It was no secret which school board members supported Mexican American Studies and which did not, but the vote never happened.

April 26 began with high attendance, in part because students had rallied community support for Mexican American Studies. The boardroom was so packed, many community members had to stand outside. While the hallway filled, chanting began, despite new TUSD regulations meant to eliminate demonstrations during meetings. Fifteen minutes before the meeting started, a group of nine students seated inside stood up, moved past the numerous news cameras, and ran up behind the TUSD board dais. The students belonged to a group called United Non-Discriminatory Individuals Demanding Our Studies (UNIDOS), a grassroots, radical youth collective founded in January 2011 to defend ethnic studies, and Mexican American Studies in particular. The first student ran straight into a security guard. As he attempted to grab her, the other eight revealed hidden chains around their waists and locked themselves to the board members’ seats. The students began to chant with fists raised high, “Our education is under attack! What do we do? Fight back!”

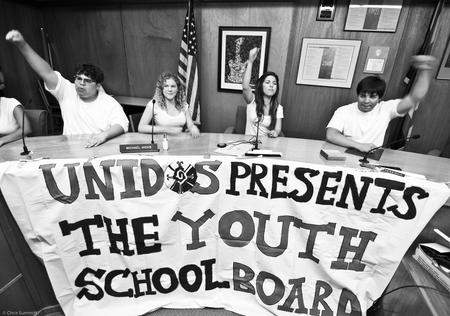

The community immediately piled into the board room, megaphones held in the air, while several more students ran up to the dais to hang up a hand-painted canvas banner that read, “UNIDOS Presents the Youth School Board.” Police were waiting outside but the TUSD board ordered them not to enter the room. The demonstration continued peacefully. The chanting only lowered when the students’ media team read from their Ten Point Resolution, demanding the repeal of HB 2281, an end to school closures, an accountable school board, and the preservation of Mexican American Studies.

There was still tension in the air as the police presence grew outside, but the students continued their peaceful act of civil disobedience. The room responded with thunderous applause when it was announced that the board meeting was postponed. Three hours later, TUSD Superintendent John Pedicone negotiated with adult allies in the audience and ultimately decided not to press charges against the students. The demonstration evolved into a community celebration. Two youth mariachi musicians climbed onto the TUSD dais to play music for the room. Everyone danced, laughed, chanted. No one was hurt. No arrests were made. There was no official board meeting and therefore no vote, which meant Mexican American Studies remained intact for the time being.16

*

The student organizing that led up to April 26 began as an offshoot of Save Ethnic Studies, a teachers’ group that filed a lawsuit on October 18, 2010, challenging the constitutionality of HB 2281.17 In December 2010, students began to question why their voice was not part of the discussions surrounding Mexican American Studies, especially since it was their education that was at stake. These students formed UNIDOS in the first week of 2011, and they began a political discussion group that met each Saturday, creating their own autonomous space to discuss how to defend their education. The students began to organize themselves. They wanted to be at the forefront of the struggle, to remind the school district who the classes were for.

After the April 26 action, numerous commentators both locally and nationally weighed in. The Arizona Republic ran an editorial titled, “Who’s in Charge at Tucson Unified?” It described April 26 as “chaotic political theater” and called on adults to “reassert themselves.”18 Glenn Beck called the action an instance of juvenile “rage.”19 Pedicone wrote an editorial claiming, with scant evidence, that the protest occurred because “adults used students as pawns.”20 These commentators all made problematic assumptions: that students do not possess social agency, that their action was spontaneous—akin to throwing a temper tantrum—and that “restoring order” involves adults regaining control of the situation. These discussions were devoid of the notion that the students on April 26 were thoughtful, intentional, and purposeful in their actions. Interviews with student activists contest the assumptions. As one participant in the April 26 action explains (because of continued police harassment, we are maintaining the students’ anonymity):

I hoped that the school board would stop ignoring us and stop treating us as if issues discussed in school board meetings were not of our concern and should be left up to the adults to handle. In fact, every decision made in that room is of huge concern for us as students. I also hoped to make them realize we’re not just kids hollering outside buildings for the heck of it. When we say we’re defending our classes, we mean business.

This passion was tempered with a critical analysis of both the district and the state’s anti-Latino atmosphere within which the attacks on Mexican American Studies occurred. The students began educating themselves on grassroots organizing. They met on the weekends and studied the teachings of the Zapatistas, the Black Panthers, and Dr. King. They focused on redefining the term resistance, and worked to become critical analysts and media strategists who could create the space for other youth to become politically engaged. The UNIDOS members publicly asserted their political voice at a February 8 press conference outside of TUSD headquarters, just before a board meeting. They told the community that they were a youth collective fighting for Mexican American Studies. UNIDOS utilized a unique style of political expression that evening as they were joined by a DJ, MCs, and live bands.

At the February 8 board meeting, UNIDOS representatives demanded to meet with all school board members to discuss HB 2281. Due to TUSD’s many regulations, however, not all could meet at once. As a result, UNIDOS was able to meet with only two school board members: Adelita Grijalva and Judy Burns, who have been the only consistent, public supporters of Mexican American Studies classes. On March 8, UNIDOS requested a public statement from TUSD that it would protect Mexican American Studies courses. TUSD refused. For UNIDOS, the choices were clear: do nothing and allow Mexican American Studies classes to be dismantled, or respond through alternative means. One student offered the following analysis:

We felt that if we didn’t do something [on April 26], then our history would be erased. This action was needed to stop the vote and to save our roots from being slashed away. We knew what this action entailed when we decided to go through with it. Arrest was definitely something we knew could happen, but we felt this action was needed. If we didn’t stand up for what we believed in, then who would? Our job as citizens is to stop unjust laws or be pushed around unjustly. And we chose to take a stand no matter the consequences.

Displaying more moral courage than most of the adults at the April 26 board meeting, the students knew they had one chance to keep their classes intact. Instead of capitulating to the overtly racist HB 2281, they decided to fight back, putting themselves at great risk physically, emotionally, and academically. The students’ demeanor during the action was self-assured, but inside, many felt trepidation:

[I felt] a mixture of emotions: anxious, nervous, scared, but very hopeful. The reason for this was because everyone up there was risking something. I for example didn’t know the reaction my parents would have after they found out; that was scary. The overall experience was all of the above because that moment was do or die. Without our actions, the right to our history would be taken.

Another student put it this way:

We wanted to show we are not tired, we will not be moved, we will fight for education. Because as scholars of today and of the future, we are critical thinkers that will not have our essential history that connects us to who we truly are be taken away from us.

One student noted the hypocrisy of the TUSD board, a group of adults who continually preach the importance of civic engagement, and their reaction to UNIDOS student act of civil disobedience:

You have education figures telling students to take charge and become active for their education, to be heard and create change. Then you have youth and community alike act in civil and responsible ways for over a year and still be ignored. Then to have those same figures become angry with the youth for standing up and taking radical action that was youth led, youth empowered, youth organized is absurd. Not only was [April 26] worth it, it was necessary!

Without the UNIDOS students’ efforts, the Stegeman Resolution would have passed and Mexican American Studies would have been dismantled. In most areas throughout the country, teenagers are trying to avoid going to school. In Tucson, we have the opposite: students fighting for their rights, risking everything for their education. The struggle continues, and as one student said:

Our classes are still being attacked to this day, but UNIDOS will not stop till there is equitable education for all.

*

In response to the April 26 action, the community was met with the militarized rescheduled board meeting of May 3 described at the beginning of this article. Instead of celebrating the civic engagement of students fighting for their education, the TUSD School Board viewed them as a threat. There was never an analysis of how TUSD systematically ignored the student voice or how the Stegeman Resolution vote brought about the actions of April 26. Instead, the students were framed as uncivil, out of control, and unproductive. Their example, however, motivated a number of adult community members at the May 3 board meeting to put themselves at the same physical risk to defend Mexican American Studies. For now, the classes are still intact, but the struggle continues. The lawsuit from the TUSD teachers is still tied up in the courts. The TUSD School Board appealed the Huppenthal ruling which found TUSD out of compliance with A.R.S. § 15-112, despite the findings of Huppenthal’s $110,000 handpicked external audit concluding the opposite (i.e., that Mexican American Studies was in compliance with A.R.S. § 15-112).21 The community was awaiting the judge’s decision in mid-November. Regardless of the outcome, the actions of UNIDOS serve as continual inspiration throughout the community, as this group of informed, dedicated, insightful, and above all brave students reignited the movement in the fight for ethnic and Mexican American Studies.

Dr. Nolan L. Cabrera is an Assistant Professor in the University of Arizona’s Center for the Study of Higher Education, and an ethnic studies graduate from Stanford University. Elisa L. Meza is a fourth-year undergraduate at the University of Arizona studying English and Mexican American Studies, and is a member of UNIDOS. Roberto Dr. Cintli Rodriguez is an Assistant Professor at the University of Arizona in the Mexican American Studies Department and a member of the Mexican American Studies Community Advisory Board.

1. Tom Horne, “Finding by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction of Violation by Tuscon Unified School District, Pursuant to A.R.S. §15-122(B),” Save Ethnic Studies, December 30, 2010.

2. Cabium Learning, Inc., “Curriculum Audit of the Mexican American Studies Department Tucson Unified School District,” Save Ethnic Studies, May 2, 2011.

3. Directed by Three Sonorans, “The TUSD Tragedy - Save Ethnic Studies,” 2011, vimeo.com/23516724.

4. State of Arizona House of Representatives, “House Bill 2281,” 2010.

5. Horne, “Finding by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction of Violation by Tuscon Unified School District.”

6. Ibid, 7.

7. Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003).

8. Otto Santa Ana, Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse (University of Texas Press, 2005).

9. Arizona State Legislature, Bill Status Votes for HB2281-Final Reading.

10. Tom Horne, “Interview by Gary Tuchman, Visiting an Ethnic Studies Class,” CNN, May 20, 2010 (time 1:53).

11. Horne, “Finding by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction of Violation by Tuscon Unified School District.”

12. D.A. Morales, “Video: John Huppenthal to ‘Stop La Raza’ Today?” TusconCitizen.com, June 15, 2011.

13. Alexis Huicochea, “Board Won’t Challenge Law,” Arizona Daily Star, January 14, 2011.

14. Mark Stegeman, “Mark Stegeman: Ethnic Studies,” (webpage), markstegeman.com/p/ethnic-studies.html.

15. Mark Stegeman, “TUSD President Stegeman Offers Perspective on Mexican American Studies Debate,” Tucsoncitizen.com, June 15, 2011.

16. To view footage from inside the board meeting, see: Three Sonorans, “UNIDOS Takes Over TUSD School Board,” YouTube, http://youtu.be/tPZxCDMbZec.

17. Save Ethnic Studies, saveethnicstudies.org.

18. The Arizona Republic “Who’s In Charge at Tucson Unified?” (opinion), April 28, 2011.

19. Media Matters for America, “Beck Fearmongers Again About Arizona School’s Ethnic Studies Program,” (video), May 5, 2011.

20. John Pedicone, “Adults Used Students as Pawns in TUSD Ethnic Studies Protest,” Arizona Daily Star, May 1, 2011.

21. John Huppenthal, “Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal Rules Tucson Unified School District out of Compliance with A.R.S. § 15-112,” (press release) Arizona Department of Education, June 15, 2011; Cabium Learning, Inc., “Curriculum Audit of the Mexican American Studies Department.”

Read the rest of NACLA’s November/December 2011 issue: “Latino Student Movements.”