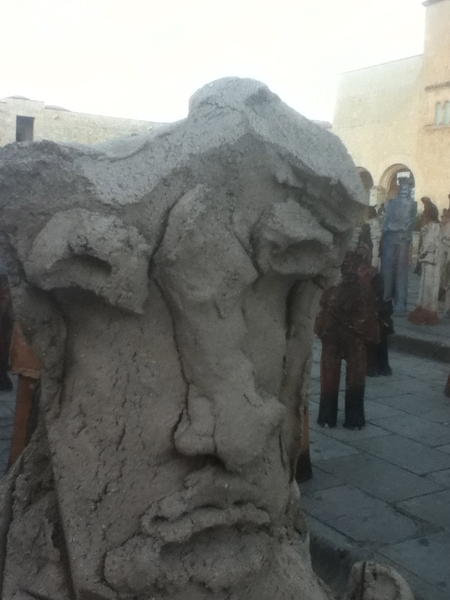

On December 29, artist Alejandro Santiago placed 2,501 individual human-sized sculptures in the streets of Oaxaca City, Mexico, all representing people who had migrated away from his hometown of San Pedro Teococuilco, Oaxaca.

Santiago said that when he returned to Teococuilco after a long absence in the late 1990s, he discovered that more than half of the population of the town was no longer there. He said:

“The only noise we heard when we returned, was our own. When everybody decided to leave to migrate, everything became empty and alone. My friends were no longer there. My aunts and uncles were no longer there. My cousins were no longer there.”

2,500 people had left Teococuilco and migrated elsewhere.

Santiago described it as a “painful absence” and began to recreate “their souls” with the clay sculptures, one by one by one. It took him six years, he said, to "repopulate his town." The cumulative expression behind their silent stares tells the “story behind the numbers and statistics.”

These sculptures in the centro of Oaxaca City, says journalist Octavio Velez in the Mexican daily La Jornada, are a public interaction with a “dynamic that affects thousands of Oaxacan families and whose consequences are, in the majority of cases, devastating." Velez says that it is not only the "loss of human life in the balance, but also because of the uprooting . . . and abandonment of communities which, in some cases, have been there for hundreds of years.”

The exodus of people out of the Oaxacan countryside to Mexico City, northern Mexico, and the United States has been dramatic. Facing structural poverty that leaves 76% of the state in constant struggle, Oaxacan organizations estimate that 250,000 are leaving the state per year. Their departure is not only dramatic, Santiago explains with his work, but painful.

This is the pain that never makes it into discussions in the United States of comprehensive immigration reform.

And it is a pain that has rarely, up to Santiago’s exhibition, been documented.

For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. And now you can follow it on twitter @NACLABorderWars. See also "The Border: Funneling Migrants to Their Doom," by Óscar Martínez, in the September/October 2011 NACLA Report, the May/June 2011NACLA Report, Mexico's Drug Crisis; and the May/June 2007 NACLA Report, Of Migrants & Minutemen.