On April 6, U.S. Customs and Border Protection finally issued a formal solicitation for proposals from private companies to continue the “virtual wall” project, which Department of Homeland Security (DHS) temporarily suspended in January 2011 (when it was known as SBInet, and Boeing was in charge of its implementation). The solicitation is “for a much-discussed purchase” of integrated fixed towers, which will be stationary  and located initially in Arizona to help the U.S. Border Patrol do video surveillance and detect human movement with radar and other sensors. Because of this and other opportunities, military and security companies are lining up in hope of getting border DHS contracts. There is a buzz among such companies that, as overseas wars wind down, there will be money to be made on border enforcement. In that spirit, I will be dedicating a series of posts on border enforcement technology, which will include interviews that I have done with several border enforcement tech companies, attending the Border Security Expo in Phoenix (which took place in March), and the participation of higher education in this process. I will particularly explore manifestations I have seen of a potentially emerging industrial complex.

and located initially in Arizona to help the U.S. Border Patrol do video surveillance and detect human movement with radar and other sensors. Because of this and other opportunities, military and security companies are lining up in hope of getting border DHS contracts. There is a buzz among such companies that, as overseas wars wind down, there will be money to be made on border enforcement. In that spirit, I will be dedicating a series of posts on border enforcement technology, which will include interviews that I have done with several border enforcement tech companies, attending the Border Security Expo in Phoenix (which took place in March), and the participation of higher education in this process. I will particularly explore manifestations I have seen of a potentially emerging industrial complex.

I begin this series by writing about a trip I recently took to the compound of the civilian vigilante group American Border Patrol (ABP), right on the U.S.-Mexico border, in the San Pedro Valley, in Hereford, Arizona (about two hours south of Tucson, between Douglas and Nogales). It was here that the first Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) did surveillance over the U.S.-Mexico boundary, not by Customs and Border Protection, but by the ABP.

In February, I made an appointment to see Glen Spencer, president of ABP, which says it’s the only non-governmental organization that monitors the border on a regular basis, mostly by air. ABP has been designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, but that is not the reason for my visit. Nor did I go because Spencer believes in the Reconquista, the idea that Mexico is again attempting to takeover the territory lost after the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Much of this has already been covered, and Spencer’s life has been written about by many people. On this trip, instead of focusing on what made Spencer and the ABP an easy target for criticism, I wanted to focus on what he and his organization share in common with the mainstream position on immigration enforcement.

border on a regular basis, mostly by air. ABP has been designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, but that is not the reason for my visit. Nor did I go because Spencer believes in the Reconquista, the idea that Mexico is again attempting to takeover the territory lost after the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Much of this has already been covered, and Spencer’s life has been written about by many people. On this trip, instead of focusing on what made Spencer and the ABP an easy target for criticism, I wanted to focus on what he and his organization share in common with the mainstream position on immigration enforcement.

ABP is an organization composed of only five people. They are not like the Minutemen, that rely on foot patrols. In fact, the only foot patrols Spencer claims to do are the ones in the morning with his ten German Shepherds. The members of this tiny group are the technology vigilantes. According to Deepa Fernandes in her 2007 book Targeted: Homeland Security and the Business of Immigration, ABP flew the first surveillance drone over the border in 2003. They have also become masters at using surveillance cameras and streaming their footage over the internet in real time. Now ABP has unveiled its newest technology, the sonic barrier. Spencer assures anyone who will listen that it “will solve the border problem.” Using seismic technology employed by companies for oil exploration—based on Spencer’s previous vocation in the field—the ABP president claims to have devised a solar-powered sensor detection system that will do what previous “virtual wall” technologies failed to do, “secure the border.” It can detect not only people, but vehicles, aircraft, and even tunneling within 200 yards of where they are placed, Spencer claims.

* * *

The signs at the entrance of Spencer’s 100 acre property—where I arrive after traveling on a labrynth of dirt roads—begin to tell the ABP story. The first one reads: “If you don’t live here, you don’t belong here, get out.” I pause briefly and then continue. The next sign says: “Respect the Flag, You MoFo.” "OK," I think. "I am going the right way." At the time I don’t notice the cameras, nor the fact that I am driving through a corridor of an elaborate sensor system, as Spencer will tell me later.

That's when I see the sign I am waiting for: “American Border Patrol: America’s Eyes on the Border. (Drug smugglers/addicts don’t like us.)”

I drive up a steep hill to a couple of buildings, one of them labeled "Border Technology Inc.," my destination. A group of dogs eye me warily. No one's around and I don’t know where I’m supposed to go. I drive into a gravel lot with a few scattered vehicles, park, and step out of the car. The dogs are not happy with my presence. One in particular, with floppy ears, begins to growl.

I quickly hear the motorized whine of vehicles moving at a high speed to my right. Two all-terrain vehicles are speeding down the dirt road toward me, in single file. Their entrance is so dramatic that I don’t know what to do. One of the vehicles comes skidding to a stop in the middle of the gravel lot, kicking up small stones, 10 feet away.

I quickly hear the motorized whine of vehicles moving at a high speed to my right. Two all-terrain vehicles are speeding down the dirt road toward me, in single file. Their entrance is so dramatic that I don’t know what to do. One of the vehicles comes skidding to a stop in the middle of the gravel lot, kicking up small stones, 10 feet away.

“Todd Miller?” The man asks stepping off his ATV.

“Yes,” I say extending my hand.

“Glenn Spencer,” he says shaking my hand, while turning his head to the other guy, Mike King, the ABP’s technology expert.

“It’s OK,” he yells to King. “All is safe.”

Spencer, of course, is controversial. In March, Arizona senator Sylvia Allen invited Spencer to speak before the Border Security, Federalism, and States’s Rights committee. She didn’t use Spencer’s name, though, but rather the name of his company, Border Technology Inc., through which he wanted to give a presentation of the sonic barrier technology: not such an off-the-wall idea considering this state wants to build its own border fence and start its own volunteer militia. The two democrats in the committee immediately walked out of the meeting when they saw that Spencer would be speaking, in protest to both anti-Mexican and anti-semitic statements he has made in the past.

We stand at the top of a hill and Spencer points down at the massive wall he has constructed on his property in front of the real border wall. He tells me, and then insists, that he actually has the same basic message as the Democrats and Obama. As he talks I’m captivated by Spencer’s massive blue roughly 200-foot-long wall. In giant letters it reads, “SECURE THE BORDER.” On the other side of that wall is the state of Sonora, Mexico, that extends into the horizon under a vast cloudy sky. The large metal wall, t he real wall built as a result of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, demarcates the line between Sonora and Arizona and continues ¼ mile to the east into the San Pedro river valley, a riparian, environmentally sensitive area constantly defended by environmentalists against further encroachment of the border security apparatus. To the west, the border wall extends as far as the eye can see, before it disappears into the Huachuca mountains, a range that crosses the U.S. -Mexico boundary unimpeded. Set amid this dramatic landscape is Spencer’s “SECURE THE BORDER” sub wall, which seems almost like a monument to the anti-immigrant forces in United States. But no, Spencer insists, this is for everybody, because everybody agrees with this.

he real wall built as a result of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, demarcates the line between Sonora and Arizona and continues ¼ mile to the east into the San Pedro river valley, a riparian, environmentally sensitive area constantly defended by environmentalists against further encroachment of the border security apparatus. To the west, the border wall extends as far as the eye can see, before it disappears into the Huachuca mountains, a range that crosses the U.S. -Mexico boundary unimpeded. Set amid this dramatic landscape is Spencer’s “SECURE THE BORDER” sub wall, which seems almost like a monument to the anti-immigrant forces in United States. But no, Spencer insists, this is for everybody, because everybody agrees with this.

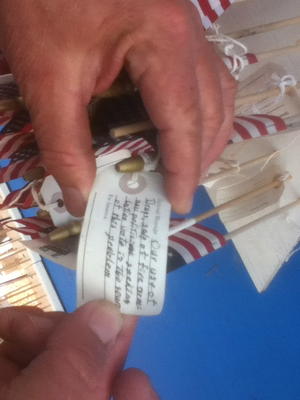

Each letter is composed of hundreds of U.S. flags, each with a small tag and a message from what Spencer says is more than 10,000 supporters that support ABP’s quest.

“Everybody wants the border secure,” says Spencer. He is adamant about this point and insists that everyone agrees, regardless of their political position.

“There’s a consensus that we need the border secure,” Spencer says with emotion. “The president said, ‘I have made securing the southwest border a top priority since I came to office.’ The President!” He is quoting Obama when he signed the Southwest Border Security Bill in August 2010.

“ 'Border Security is paramount,’ ” Spencer says continuing the quotations, this time by Texas Senator Kay Hutchison.

“Even Harry Reid says this.”

He pauses then exclaims, “Even the human rights activists!” He searches for another quote “from Colorado Human rights.” And he finds the phrase: “First of all we all want a secure border…” he says, quoting Julien Ross, the Colorado Human Rights Coalition Director.

“Everyone agrees. Left, Right, Center, top, bottom, we’ve got to secure the border. There’s no dispute. It’s a given. Stipulated.”

* * * *

While Spencer’s years of racially charged commentary is  roundly condemned, his actions and insistence that the border needs to be secured, is hardly controversial. The notion that border security—which includes both the imposition and hard-line policing of the boundary line—could be a racial, violent act is left unexamined.

roundly condemned, his actions and insistence that the border needs to be secured, is hardly controversial. The notion that border security—which includes both the imposition and hard-line policing of the boundary line—could be a racial, violent act is left unexamined.

Democrat Ron Barber, who is running for Gabrielle Giffords former congressional seat, (a congressional district that covers Hereford, Arizona) sounds a lot like Spencer when he describes the need for “border security.” Like Obama, Barber insists will be a priority. In a March interview with the Arizona Daily Star, Barber highlighted "several tools needed to bolster border security: highway checkpoints, more ‘boots on the ground,’ technology to detect illegal crossings and the use of drones for surveillance.” The fact that Barber sounds like Spencer is nothing new or astonishing. This type of language is embraced, not chastised, much less even discussed.

Nevertheless, in their article, Keeping Migrants in Their Place: Technologies of Control and Racialized Public Space in Arizona, scholars Meghan G. McDowell and Nancy A. Wonders believe that there are racially-charged impacts of the type of surveillance state sought after by Spencer, Barber, and across the Republican Democrat divide. They write that “the act of surveillance and the resulting internalization of the security gaze work together to effectively regulate the mobility of migrants, restricting them from public space.” They quote Christian Parenti who says that “the electronic dragnet will force internalization of the [surveillance] gaze, causing immigrants to keep to themselves, stay out of sight, and steer clear of politics." McDowell and Wonders believe that this intense surveillance apparatus, both at the border and beyond, is causing a dynamic of self-segregation among people who live in the United States without papers. This, in effect, creates a deep racial,

economic, social, and political divide between peoples, where migrants often avoid public spaces—including hospitals, police stations, and libraries—due to internalized fear.

economic, social, and political divide between peoples, where migrants often avoid public spaces—including hospitals, police stations, and libraries—due to internalized fear.

It is easy to simply cast off somebody like Spencer as a racist, and throw him to the fringe. However, I contend that he might not only be a manifestation of mainstream and official thought on immigration and border enforcement, but also in some ways the vanguard. After flying his UAV missions with the Border Hawk in 2003, Deepa Fernandes reports in Targeted that Department of Defense officials visited him to learn more about this drone technology. Although Spencer never received a contract from the federal government, it was soon after that CBP started flying its unmanned Predators on surveillance missions over the borderlands.

Who knows if the sonic barrier, with its seismic technology of oil

exploration, will also bring such official attention, but Spencer clearly thinks so:

exploration, will also bring such official attention, but Spencer clearly thinks so:

“It is technology that we’ve been working on for 10 years,” he says, “It detects and counts everyone who crosses the border. We can instrument the entire U.S.-Mexico border for less money and count everybody than Boeing wasted on 50 miles in Arizona. No question about it, it will be done. With that, the border problem will be solved.“

While Spencer might be a little more cocky and arrogant than the norm, there is little difference between his pitch, and the pitch of hundreds of tech companies lining up in hopes of getting a CBP contracts, peddling products ranging from drones to towers, cameras to sensors, and much more. But these companies don’t quite express things as Spencer does: they don't say that the technology will be used to pursue “illegals.” Instead the companies are responding to demands from people, including President Obama and Democrat Ron Barber, who, at the end of the day, do have a “secure the border” consensus with Spencer and ABP. Because of this, border enforcement technology, or so the buzz goes, is a sure-fire growth industry.

For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. And now you can follow it on twitter@NACLABorderWars. See also "Undocumented, Not Illegal: Beyond the Rhetoric of Immigration Coverage," by Angelica Rubio in the November/December 2011 NACLA Report; "The Border: Funneling Migrants to Their Doom," by Óscar Martínez, in the September/October 2011 NACLA Report; and the May/June 2007 NACLA Report, Of Migrants & Minutemen.