The following book review was published in the Summer 2012 issue of the NACLA Report on the Americas, "Latin America and the Global Economy."

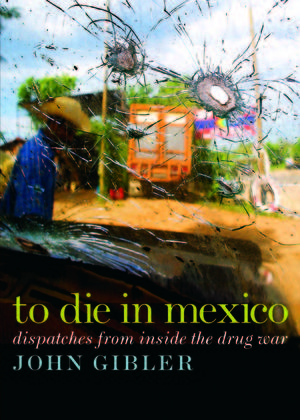

To Die in Mexico: Dispatches From Inside the Drug War, by John Gibler, City Lights Publishers, 2011, 218 pp., $15.95 (paperback)

Over 50,000 Mexicans have been killed since President Felipe Calderón launched his war on drug traffickers in 2006. Despite the heavy presence of soldiers and federal police on the streets of the country’s most contested drug trafficking territories, the body count rises daily, and gruesome stories of beheadings and mass graves have become all too familiar. Corruption is rampant in Mexico and justice elusive—only 5% of drug war deaths are investigated and even fewer are prosecuted.

Media coverage of the drug war sensationalizes the violence and death, excluding the details of human life and survival. Government reports and the growing body of literature on the topic largely focus on the state and the cartels, ignoring the drug war’s effect on individuals and the role civil society is playing in resisting the violence. Writer and reporter John Gibler fills this void with his second book, To Die in Mexico: Dispatches From Inside the Drug War.

Gibler, who has lived and worked in Mexico since 2006, writes from the front lines of the country’s most dangerous cities, combining in-depth interviews with his own vivid reporting and analysis of the global drug prohibition regime. In five short chapters, To Die in Mexico expertly weaves together the larger narrative of the U.S. war on drugs, the staggering statistics of the global narcotics industry, and the historical framework within which Mexico’s powerful cartels have arisen, with personal tales of loss, survival, and perseverance. The result is an action-packed and deeply informative account of the violence that takes the reader from bloodied crime scenes and state prisons to the plazas controlled by cartel gunmen and campuses where citizens are mobilizing for peace and justice. To Die in Mexico provides a glimpse into a situation that is both terrifying and desperate.

The horrors of Mexico’s drug war are even more disturbing when understood within the historical context of the U.S.-led War on Drugs. Narcotics prohibition has been a failure from the start. The violence and bloodshed are a predictable consequence of the black market created by making drugs illegal, a lesson that should have been learned from alcohol prohibition, the so-called noble experiment that so clearly failed. It appears nothing was learned. After 75 years, the effectiveness of drug prohibition has been proved by neither scientific evidence nor historical experience.

“Decades of narcotics prohibition has produced the highest number of drug users in history, the largest prison population in the world—disproportionately people of color—and police forces that subsidize themselves from assets seized during drug-busts,” writes Gibler. Why then is the United States so committed to prohibition?

To Die in Mexico explores these motivations by examining the racist origins of drug prohibition. Gibler writes that the drug war “is a proxy war for racism, militarization, social control, and access to the truckloads of cash that illegality makes possible.” He cites Ohio State University law professor Michelle Alexander’s 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which argues that the U.S. War on Drugs is a form of racial control designed to keep minorities as second-class citizens. Indeed, it is impossible to ignore the racial inequalities that have resulted from the policy. In the United States, African Americans make up 14% of drug users, yet represent 37% of the population imprisoned for drug offenses. African Americans also serve nearly as much federal prison time for drug offenses as their white counterparts do for violent crimes. The war on drugs has also been used as an excuse for continued interventionism in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the United States has imposed its policy from the coca-growing regions of the Andes to the U.S.-Mexico border, threatening to withdraw economic assistance to countries that do not comply with prohibition policies.

The historical context provided in To Die in Mexico is essential for understanding the current drug war in Mexico. Gibler covers the political, social, and economic factors that have contributed to the violence, convincingly making the case that “absolute prohibition is legislated death.” Yet the true lifeblood of the book is the personal stories that Gibler tells through his interviews. Despite its title and thorough grounding in the disturbing reality of Mexico’s narco-violence, To Die in Mexico is focused on life—the lives of Mexicans who have lost loved ones, the journalists who cover the drug war in spite of its dangers, and even the lives of the dead, who would otherwise remain anonymous.

Gibler provides a human perspective that is often lost in mainstream coverage of the drug war, and it is desperately needed. Newspapers will print disturbing photographs of mutilated bodies along with the death toll, but they will not print the names of victims or perpetrators, or attempt to uncover a motive—to do so would be inviting violence, and too many journalists have already been killed or disappeared. Out of self-preservation, journalists censor themselves. Ernesto Martínez, a photographer for Culiacán’s main tabloid newspaper, tells Gibler: “Investigative journalism is dead here.”

By sharing the stories of Martínez and others working on the ground, Gibler challenges the silence and gives voice to the dead, opposing the commonly held assumption that those killed in the drug war were involved in the drug trade and that their deaths were therefore justified. Through interviews with journalists, human rights activists, and other ordinary citizens, Gibler reveals the human side of the inhuman violence—the fear, the suffering, and the frustration. One woman he interviews in Sinaloa, Mercedes Murillo, the sister of a slain journalist, voices her frustration with the Mexican government’s inability to rein in the violence.

“The only thing organized, well-organized, in Mexico is organized crime,” she says. “People have lost all faith in the authorities, the only thing in this war that we can believe is in the dead.”

It is not surprising that many Mexicans, surrounded by corruption and impunity, feel that the war on drugs is hopeless. Javier Valdez, a veteran journalist based in Culiacán, describes himself to Gibler as “an activist of pessimism.”

“The worst of it is not only the dead, but also the lifestyle that narco imposes on us all,” says Valdez. “I am speaking of the fear. We have already ceded the public parks and the park benches to the narcos, to fear. And I think that is the worst loss. This society is ill.”

Another crime reporter, Luz del Carmen Sosa, based in Ciudad Juárez, also speaks about the toll that the violence takes on the living. What most affects her is “to see how the families get destroyed; to watch how a mother screams, desperate; or to see how a child cries because they killed her parents.”

Fear has paralyzed many in Mexico, but Gibler’s interviews reveal that amid the paralysis, the silence and the culture of impunity are not going unresisted.

“There are newsrooms where narcos call the shots, whether by bribe or by bullet,” writes Gibler, but many journalists continue to risk their lives to cover crime, refusing to be silenced or censored by fear. Out of a situation of hopelessness and terror, there are people who persevere. Knowing that they cannot find justice within a system based on corruption and impunity, individuals are taking action.

One of the most moving stories in To Die in Mexico is that of Alma Trinidad, whom Gibler describes as “a lonely foot soldier of hope in a hopeless, desperate war.” Trinidad’s son was one of 11 people killed in a massacre in 2008. Years after his killing, the suspected perpetrators have not been arrested, though their names and whereabouts are known. Investigators admit that they are afraid to get too close to the case. Although Trinidad says she has lost hope, she continues to demand justice and, together with other mothers who have lost children to narco-violence, has started a nonprofit called Voices United for Life, seeking to resist government silence and inaction.

Despite the odds, the strength of Trinidad and others like her has begun to plant a seed of change. A movement is growing in Mexico, and citizens are mobilizing to overcome fear and take back their streets. The last chapter of To Die in Mexico drives home the failures of the drug war and emphasizes the challenges that lie ahead of reforming drug laws and reducing violence, but in the last few pages, Gibler highlights the growing grassroots movement for peace, suggesting that it may offer hope.

In March 2011 Juan Francisco Sicilia, the son of poet Javier Sicilia, was found killed, along with six of his friends, leading his father to found the Movement for Peace and Justice With Dignity and launch a peace caravan that has moved thousands of Mexicans to protest the violence in over 40 cities. Sicilia spoke his son’s name, reminding the country that behind the death toll there are human lives, and encouraged people throughout Mexico to hang plaques with names of the dead on government buildings, creating what Gibler calls a “rebellion of names in a war of anonymous death.”

Sicilia’s movement offers a glimmer of hope in Mexico’s charade of death, but there is a long road ahead. Murder and impunity continue. Several movement activists have been killed or abducted since To Die in Mexico was published in 2011. Though a wave of support for the legalization and decriminalization of drugs is spreading across Latin America, spearheaded by some of the region’s top leaders, the Obama administration remains committed to prohibition, unwilling to take the political risk of participating in a debate on such a contentious issue. Yet, with presidential elections this year in both Mexico and the United States, this issue should be on the agenda. As Gibler reveals, Mexican civil society is starting to demand a change, and Gallup polls show that more U.S. citizens now favor legalizing marijuana than at any other time in history.

To Die in Mexico does not pretend to offer an easy solution to Mexico’s drug war, but the voices of survival and courage in the face of the country’s brutal narco-violence are a testament to the strength of the human soul and a reminder to keep fighting for the change we want to see.

Anila Churi is the Circulation and Sales Manager for NACLA Report on the Americas. She has an M.S. in Global Affairs from New York University, where she completed her thesis on U.S. policy in Mexico’s drug war.

Read the rest of NACLA’s Summer 2012 issue: “Latin America and the Global Economy.”