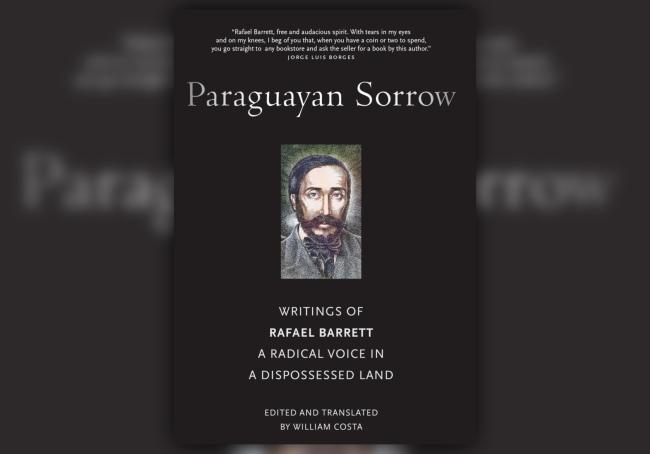

Not every island is surrounded by water. Augusto Roa Bastos, possibly Paraguay’s most renowned writer, famously described his country as an island surrounded by land, isolated from the world by “the immensity of its jungles, its impassable deserts.” It was to this landlocked country in the heart of South America that Spanish journalist Rafael Barrett was posted in 1904. Paraguayan Sorrow, originally called El Dolor Paraguayo, collects Barrett’s writings during the brief years he spent there, until his premature death in 1910.

Born to a Spanish mother and an English father, Rafael Barrett had grown up amongst Spain’s privileged classes, and he soon made his name amongst Paraguay’s liberal bourgeoisie. But he just as soon turned his back on that bourgeoisie and instead devoted himself to writing about —and against— the social injustices and sorrows that afflicted his new home country.

Barrett rallied against the exploitation of workers by landowners and corporations, as well as the corruption and ineffectuality of public institutions. The poverty and dispossession that resulted from these combined factors were also compounded by the enduring devastation of the War of the Triple Alliance (1864 – 1870), which had pitted Paraguay against the combined forces of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, and decimated Paraguay’s development plans. Measured in per capita terms, this might have been the world’s deadliest war of the last two centuries, as around half of Paraguay’s population perished.

Barrett’s articles cost him marginalization from Paraguay’s intellectual and political elites, and eventually deportation from the country. But they succeeded in inspiring generations of workers, writers, and activists throughout South America, as well as earning him praise from some of the continent’s best-known authors, including Jorge Luis Borges, Eduardo Galeano, and Roa Bastos, the latter of whom described Barrett as the “Discoverer of Paraguay’s social reality.” Barrett’s work continues to inspire left-leaning thinkers and doers.

International readers will find much that is valuable and inspiring in this book, even if they do not have a special interest in Paraguay. Despite the explicitly national flavor of its title, the core themes that run through Paraguayan Sorrow resonate broadly in space and time. No doubt thanks to his international education and background, Barrett was able to quote, compare, and draw inspiration from writers and case studies from around the world. But, more fundamentally, the root causes of the Paraguayan ills identified by Barrett—the exploitation, the corruption, the ineffectuality—relate directly to the human spirit itself. Barrett saw greed, callousness, and the self-serving interests of the bourgeois elites as the ultimate causes of human misery and injustice.

Consequently, Barrett’s solutions to these problems were also spiritual. In his view, a better society would emerge from greater love and solidarity toward humans and nature, as well as vitality and determination to overcome what he saw as a “morbid resignation” to our misfortunes (morbid because resignation led Paraguayans to continue to suffer from the aforementioned ills). Perhaps echoing Seneca, the Roman Stoic from Córdoba, Barrett saw lasting sorrow as akin to laziness: a failure of the will to shift affective gears and take control of our own emotions.

It is in light of this last insight that the depth of the book’s title can be appreciated. What Barrett understood is that sorrow is not just the product of our predicaments, but also their producer. During a two-week trip to Paraguay a few years ago, I encountered repeated invocations of the War of the Triple Alliance—one hundred and fifty years on—to excuse the country’s underdevelopment, especially with reference to Paraguay’s promising pre-war economic and industrial trajectory. But I also met those who deplored such invocations, and who wished their fellow Paraguayans would redirect their pain toward present politics and processes.

An emphasis on the ethical and the spiritual might suggest a neglect of the political. In fact, Barrett’s spurn of institutional politics—he is widely considered to have been an anarchist, and indeed he described anarchy as “common sense”—stemmed from his consideration of the failures of such politics, rather than from a blindness to or acceptance of them. One of the missions of Germinal, the newspaper founded by Barrett once he had been blocked from virtually all of Asunción’s publications, was to accept not “what is legal, but what is just.” In one of the articles that make up Paraguayan Sorrow, entitled “On Politics,” Barrett declared: “A fertile politics exists: not doing politics. An effective way of gaining power: fleeing from power and working at home.”

But Barrett’s “fertile politics”—politics that serve society, rather than fettering it with bureaucracy and corruption—extended beyond the private work of the individual. Many of his suggested avenues for overturning the law and the bureaucracies, or the infertile politics, consisted of political association and mobilization, albeit outside (and against) established institutional channels. He urged workers to organize general strikes to bring the world to a halt, and politicians to their knees. And he called for a collective wresting from landowners of the land which he saw as belonging to all people.

Indeed, Barrett venerated the land on quasi-religious terms, and at various points in Paraguayan Sorrow he showed that the fight for social justice must take ecology into account. “Everything emerges from the earth,” he explained in a speech addressed to the workers, noting that “we ourselves are earth.” Because of these and other claims about human relationships with nature, Barrett has been considered an early precursor to modern environmentalism.

But if Barrett had a message for present-day environmentalists, it is more complex than any facile calls to save nature. His eyes were unclouded by imaginaries of a wholly benevolent nature, within which all beings, including humans, cooperate. Barrett knew that plant and animal life was a matter of stealing from, strangling, and devouring each other. But he also felt that “a sublime certainty arises from the healthy cruelties of nature that is absent from the fanatical and callous cruelties of men.”

With regard to human cruelties, Barrett also strove to see clearly, and Paraguayan Sorrow never looks away from the heartless ways in which humans exploit and subjugate each other. Even in those hideous contexts, Barrett urged his readers to see humans from the disinterested perspective of the anthropologist or the social scientist whose aim is not to change society, but rather to understand it: “let us not gesticulate against the vile reality in which we must live and that—oh!—we must love. Let us study it. Let us not perceive crimes in the world, but rather facts.”

Yet Barrett’s writing was anything but disinterested; almost the entire book is animated by his drive to improve the lives of the underprivileged and the oppressed. It is here that the reader comes up against the central contradiction of Barrett’s project, which the writer himself did not appear to perceive. For all his promise of radical social change through the ethical and spiritual renewal of persons and collectives, Barrett also betrayed a pessimistic view of human nature. He wrote that torturers repeat “the eternal act common to the weak and the strong, of kicking and biting and strangling and crushing their fellow man.” In another article, he reissued the trope of man as inherently violent.

Why, then, was Barrett so optimistic about the coming of a better social order, founded on universal benevolence and solidarity? Barrett did not offer us much with which to address that question, other than a streak of Christian myths repackaged as a secular faith in man. He described the strike-induced standstill he envisioned as “the final judgment from which future society will arise,” a society governed by justice, equality, and a more beautiful humanity. Barrett even described this worldwide emancipation of workers as “a savior descend[ing] for the second time to this vale of tears.”

Stripped of its religious origins, such a faith in humanity is hard to square with the evils Barrett perceived in human societies. The callousness, resignation, selfishness, and corruptibility described in Paraguayan Sorrow may serve as unwitting arguments against the solidarity and spiritual transformation called for in this book. Barrett, the activist, collided with Barrett, the knower of the human condition. And from that collision emerges the conundrum facing those of us who denounce what humans are capable of doing to each other while, in the same breath, believing in social improvement through human efforts.

It is a conundrum we would do well to take seriously. Barrett’s writings help us do so.

Rogelio Luque-Lora is a freelance writer and a forthcoming Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the School of GeoSciences of the University of Edinburgh.