Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, is calling for “Total Peace” in an ambitious plan to reign in growing violence among armed groups in the country, invest in conflict zones, and impose sweeping reform in the public forces. But to accomplish this, he will have to overcome considerable security challenges he inherited from his predecessor, Iván Duque, as well as resistance from political opponents and a plethora of criminal groups who have grown in power in recent years.

For conflict-ridden regions such as Chocó, Cauca, and Catatumbo, where the law is imposed by criminal groups rather than the state, massacres are common, and the killings of social leaders brave enough to demand change has become a near daily occurrence, the stakes could not be higher.

These regions have been plagued by violence for decades and were hotspots for Colombia’s 53-year civil war with leftist rebel group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Many hoped that the historic 2016 peace deal with FARC rebels might bring stability and alternatives to the black market economies that sustain armed groups in their communities, which have been long neglected by the government. Instead, a host of new criminal groups moved in to fill the vacuum left behind when the FARC disarmed and joined civil society—and the cycle of violence has continued unabated.

Petro is hoping to finally break that cycle for good.

“Without true peace, there can be no democracy,” was one of Petro’s mantras on the campaign trail. But when he speaks of “Total Peace,” what exactly does he mean?

Petro has pledged to fully implement the unfulfilled promises made by the government as part of the 2016 peace accord. These include investing in infrastructure and education in the regions formerly controlled by the FARC, as well as land-restitution for displaced communities and waiving criminal sentences in new negotiations with criminal armed groups. He has also called for a restructuring of public forces in Colombia, which have a long history of human rights violations. As part of that plan, his coalition has already begun legislation that would place the police, which currently report to military leadership, under civilian control, and impose mandatory human rights training on military forces.

He has further called for changes in drug policy that includes full decriminalization of marijuana, and an end to militarized “War on Drugs” policies that the United States has supported for decades.

The most controversial aspects of his program involves new negotiations with rebel groups, like the ELN, who weren’t party to the 2016 accord, as well as criminal armed groups like the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC)—or as the government calls it, the “Clan del Golfo”—which have origins in the paramilitary forces that fought on the side of the government during the civil war.

Petro’s plan of an integrated approach to peace-making may be “the only viable path we have to achieve real peace in Colombia,” said Kylie Johnson, an investigador at the Conflict Responses Foundation (CORE by it’s Spanish initials), “but it is a very, very difficult path to implement, full of both political and security challenges.”

Negotiating with Criminal Groups

Leftist rebel group ELN is one of the armed groups that has taken over where the FARC left off. The ELN was not part of the 2016 peace deal and has expanded its presence considerably, in both Colombia and Venezuela, since the accord was signed. Previous attempts at dialogues with the government were abandoned or scuttled, most recently in 2019, when ELN bombed a police academy in Bogotá, killing 22 people.

Shortly after Petro won the presidential elections, ELN leaders announced a willingness to negotiate with the incoming administration. Petro on Friday sent a delegation to Havana, where earlier talks with the armed group were held, and where some members of ELN leadership have lived in exile since talks stalled.

Preliminary talks, which have already begun, are being assisted by officials from Cuba and Norway, as well as representatives of the UN secretary-general, whose office has stated publicly that they view Petro’s plan “with optimism” and will work to support its implementation.

The ELN leadership and organization has changed considerably since many of the commanders have been exiled in Havana. Not only have they grown into the second-largest armed group in Colombia, but a number of commanders have been killed in Colombia by government operations, and their divisions taken over by new leadership.

Francisco Daza, a field investigador at the Foundation for Reconciliation and Peace (PARES), explained that as the group has grown in territory and power, some “blocs” have become more independent than others.

“We will know soon whether leaders in Havana still have the influence they enjoyed formerly,” he said. Much like with the FARC, he speculated that there will likely be “dissident” ELN groups, who reject whatever compromise is finally agreed upon in Cuba.

Even more unpredictable however, is how Petro’s overtures will be taken by narco-criminal groups like the AGC, which, since the 2016 accord with the FARC, has grown into the largest and most powerful armed group in Colombia.

Leading up to the first round of elections in May, the group carried out an “armed strike” across nearly a third of the country that forced businesses to close and brought transport to a halt, reaching normally secure areas just outside the city of Medellín. At least six civilians and two police officers were killed and dozens of trucks and buses burned.

They have also targeted police officers in a series of contract killings they call “Plan Pistola,” which has resulted in the deaths of 36 police officers so far this year. Despite this growing aggressivity, the group announced a unilateral cease-fire with the government on the day of Petro’s inauguration. Some factions of the group also announced a willingness to negotiate with the new government in an open letter that same day.

It is unclear, however, whether AGC has a central leadership capable of speaking for the entire organization. The group is an alliance of hundreds of semi-autonomous paramilitary and criminal groups. Further complicating negotiations is the fact that many of the group's illegal activities have roots in naro-trafficking, extortion, illegal mining, and human smuggling. Even if AGC disarms, these activities will likely be picked up by dissident groups from within the organization or new groups stepping into the vacuum.

Addressing the Roots of Conflict

Experts insist that real peace-building efforts must include alternatives to these black market activities, as well as direct consultations with the affected communities.

“Real peace isn’t just dismobilization,” said Daza. “The strategy must address the root causes of conflict in these territories as well.”

“And although AGC and ELN present challenges to comprehensive peace as the largest armed groups in Colombia,” he continued, “Petro also must keep in mind the example of FARC dissidents, many of whom returned to arms in recent years after they felt the government didn’t fulfill the promises it made in 2016.”

Miguel Suarez, of the Foundation Ideas for Peace (FIP) believes this is a critical factor. “There is a serious danger that after ELN or AGC leaves these territories new dissident groups arrive to take over, and violence simply continues, as happened after 2016 with the FARC.”

“The politics of the last 50 years of a militarized war against drug cartels has been a failure,” said Iván Cepeda, a senator in Petro’s “Historic Pact” political alliance. “We have to open a public debate about other ways of dealing with this problem.”

Previous administrations used a "peace in segments" approach without much success, he added, but Petro’s plan employs a new strategy. “The intention is to address the fundamental problems [faced by these regions] comprehensively and simultaneously.”

Suarez agreed that a more holistic approach is the only solution. “Total peace can only be achieved through a generational transformation, with investment in conflict zones and processes of humanitarian development,” he said. Every armed group in Colombia sustains itself, at least partly, through narco-trafficking, and any approach to peace-building that doesn’t deal with this root issue will not yield lasting results.

Further, decades of militarized and aggressive strategies to address this problem on the part of the government have led to grave human rights abuses on the part of armed forces, such as the “false positives” scandal, in which over 6,000 civilians were killed by security forces and recorded as guerillas in an effort to inflate casualty reports.

“The war against drugs has led the state to commit crimes against humanity,” Petro said in his inauguration speech last Sunday, “and has further damaged our very democracy.”

His administration and their allies are determined to build a new model of peace-making in regions wracked by conflict, and the United States has signaled a willingness to support these efforts. Whether Petro has the political capital to implement real transformative change remains to be seen, but popular support will be critical for the implementation of his programs.

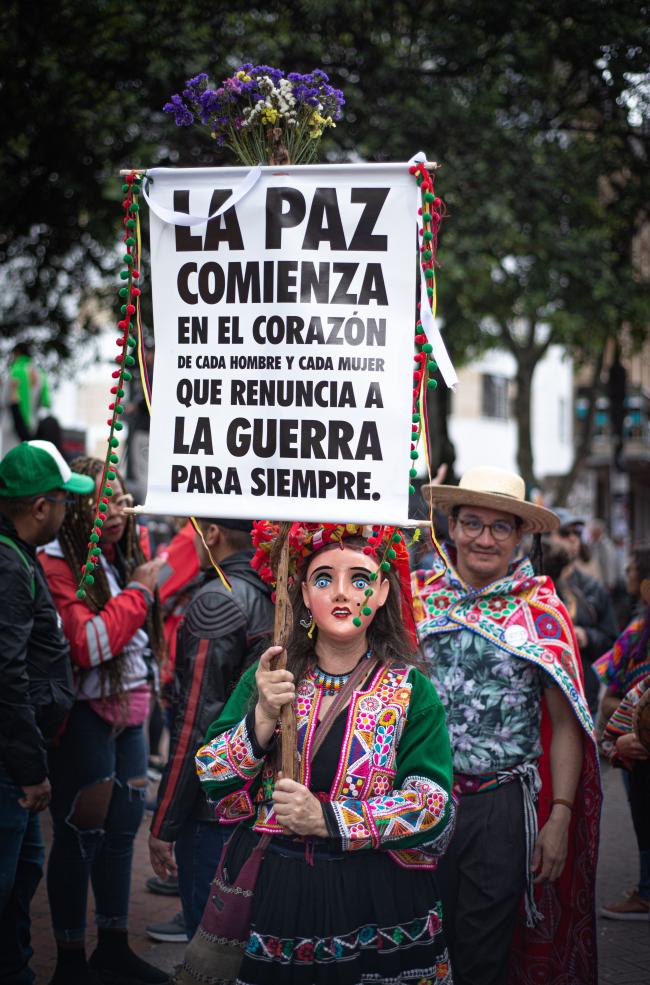

“Petro has said many times that real peace isn’t created by official dialogues between the elites and armed groups, or only by the state,” said Cepeda. “Rather it is created by citizens themselves. Their participation is fundamental.”

Joshua Collins is a freelance reporter in Colombia focused on civil rights, migration, and the impact of crime upon human rights.

Daniela Díaz is a journalist in Bogota, Colombia focused on implementation of the peace and women's issues. She has been published at VICE World News, World Politics Review, and a host of Colombian media companies.