This piece appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

As U.S. troops headed to Grenada in October 1983, most had no idea where they were going. Many had never even heard of Grenada, the smallest place the United States has ever invaded. Fewer still knew of the popular revolution that had taken root there and ultimately imploded just days before. What possible threat could a 12-by-21-mile island with a population of barely 100,000 pose to the most powerful country in the history of the world?

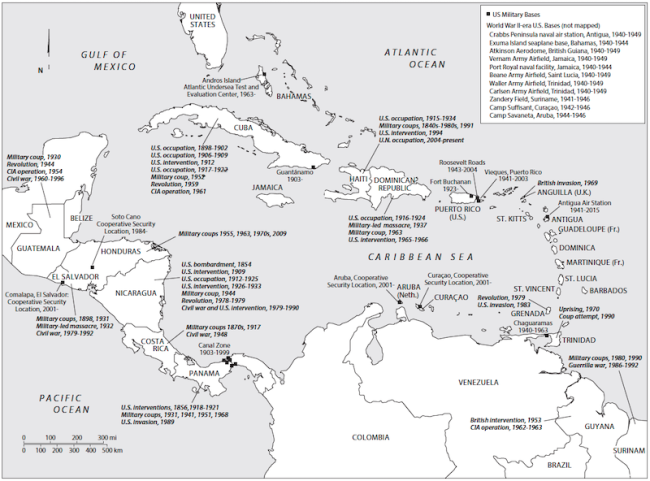

October 25, the 40th anniversary of “Operation Urgent Fury,” offers an occasion not just to remember the invasion but to reconsider how we remember it. While the invasion has been extensively documented, albeit predominantly from U.S. points of view, the revolutionary events leading up to it have received much less attention. An internationalist critique of empire demands a contestation of empire’s memory.

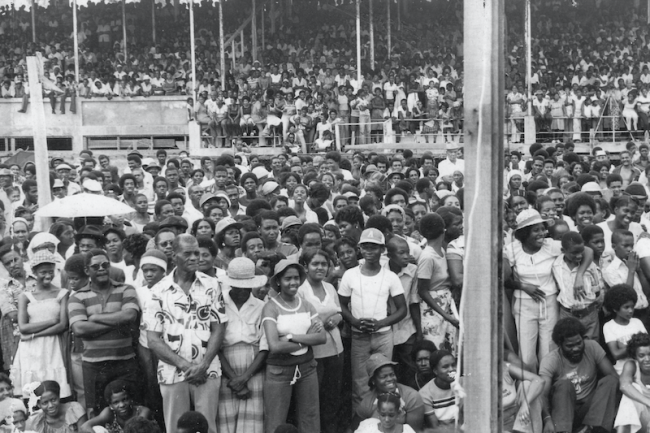

On March 13, 1979, five years after Grenada’s independence from Britain, the New Jewel Movement (NJM) mounted an armed attack against the increasingly erratic and authoritarian Prime Minister Eric Gairy. The NJM had helped unite urban and rural working-class opposition to Gairy. But both Gairy’s repression and the history of U.S. interference in the region’s elections had foreclosed an electoral path to power. In a matter of hours, 46 men with scarcely 21 weapons seized power, and Grenadians from across the political spectrum came out in support of the NJM, which took power as the People’s Revolutionary Government.

The charismatic lawyer Maurice Bishop emerged as NJM’s popular leader. Equally eloquent in the language of law courts and Creole, Bishop had been a major defender of the nurses in their 1970 strike and led the symbolic 1973 “People’s Trial” of British landowner Lord Brownlow, who had denied Grenadians access to public lands and beaches. Bishop gained further allegiance after he and other opposition members were attacked in 1973 and his father was killed in 1974 by Gairy’s paramilitary forces. Once the People’s Revolution Government took power, Bishop became prime minister. Bernard Coard, an economist and key NJM party strategist, became finance minister and deputy prime minister.

With the Revolution, the tiny isle known for nutmeg and other spices, tourism, and a medical school was suddenly thinking big. It made strides in education, literacy, health, arts, and culture. The fledgling Revolution was talking about economic diversification and modernization, free education, and expanded civic participation, governmental accountability, and regional integration. Seeking increased economic and political self-determination, it explored locally practicable paths, often breaking with traditional socialist models that nationalized industry.

Accordingly, the People’s Revolutionary Government remained pragmatic about the necessary role of tourism, business, and foreign investment. It championed a longstanding pre-revolutionary plan to replace the old airport at Pearls with a new, larger, modern international airport at Point Salines, in the south of the island, that could land larger planes. This infrastructural improvement would bring Grenada’s airport up to par with other Caribbean airports and was integral to the island’s plans for economic development. Construction began in 1980 with immense popular support, massive assistance from Cuba, and involvement of several other countries including Canada and Britain.

Internal Aggression: Self-inflicted Wounds

By 1981, the Revolution had run into internal problems. Like many revolutionary groups forced to operate in secrecy because of political repression, it had opted for a vanguard party. Once in power, the NJM had to grapple with how to resolve the fundamental contradictions between the logic of armed struggle that enabled the seizure of state power and the logic of democracy; between force and persuasion, military hierarchy and democratic equality. The Revolution drifted toward popular authoritarianism. Increasingly, it curtailed free expression, militarized society, and imprisoned dissenters. It forgot that the centralized vanguard party and the bubbling popular energies of the Revolution were not one and the same.

In October 1983, the NJM settled its own internal differences by force, too. The party machinery had gradually marginalized its more democratic voices. Amid a developing rift and internal struggle over the leadership of the Revolution, the party voted in September 1983 to redefine responsibilities, explicitly dividing them between Coard and Bishop. Opinions differ as to whether this vote for “joint leadership” merely formalized an existing division of labor, increased the party’s power, or reduced Bishop’s power. But the proposal was pitched as promoting “democratic centralism” over “onemanism.”

When Bishop did not accept the party’s vote for joint leadership, he was put under house arrest. This heavy-handed response ignored a key point: the majority will of the party did not represent the majority will of the people. Seven days later, on October 19, 1983, crowds of Grenadians stormed past the guards and freed Bishop amid chants of “No Bishop, No Revo.” They followed him up to Fort Rupert, the headquarters of the People’s Revolutionary Army, where pro-Coard forces opened fire. Bishop and seven comrades were killed as a result of orders of members of their own party.

A Revolutionary Military Council took over and declared a shoot-on-sight curfew. The country reeled. For Grenadians, the Revolution had died with Bishop, and its killers were now in power. That is why the very Grenadians who a few days earlier would have fought U.S. forces to defend the Revolution now welcomed the invasion. Most said they approved of the U.S. intervention because it saved them from Coard; only 2 percent said it saved them from communism.

For much of the Caribbean, too, it was a moment of anguish. The Grenada Revolution had carried the hopes of progressive sectors across the region. The fall of the Revolution dashed those hopes, resulting in mass disillusionment and a retreat from all organized politics, all “isms.” As the late Trinidadian calypsonian Black Stalin put it, “every ism is just schism.”

External Aggression: Pretexts and Opportunities for Empire

The internal rift and fratricide within the Revolution were a gift to the United States. Washington had been wary of the Revolution from the start. But after President Ronald Reagan entered office in 1981, the rhetoric escalated. The new Point Salines airport became the center pin of U.S. war talk. Though the airport would merely put Grenada’s air capabilities on par with several other Caribbean tourist destinations, Reagan claimed it was part of a Cuban-Soviet plot to turn Grenada into a military base for exporting revolution and terrorism. The United States also inflated the numbers of Cubans present on the island and mischaracterized them as military and paramilitary forces. By March 1983, Reagan could declare without any apparent sense of irony: “It isn’t nutmeg that’s at stake in the Caribbean and Central America. It is the U.S. national security.”

After Bishop’s murder, the military exercises that the United States had been practicing in Puerto Rico since 1981 could be carried out for real in Grenada––but now in the name of a rescue mission. Washington claimed that the 700 or so U.S. medical students at St. George’s University were at risk. Dominica’s Eugenia Charles, chief of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), and two other heads of Caribbean states, Edward Seaga of Jamaica and Tom Adams of Barbados, obligingly invited the United States to intervene in a nominally joint operation. Moreover, as chance would have it, an otherwise war-weary U.S. public was suddenly galvanized to sympathy with the military when 241 U.S. servicemen were killed in a terrorist attack in Beirut on October 23, 1983, two days before the Grenada invasion.

The armed intervention violated the OECS charter and international law and was overwhelmingly condemned by both the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly. The narrative about the medical students ran counter to students’ own perceptions and the Grenadian government’s own interests. Indeed, as CIA-officer Duane Clarridge put it in his 1997 memoir: “Besides nutmeg, the school and its students were the island’s only ‘cash crop.’” Even the Pentagon, long versed in covert and overt interventions across the Caribbean and Latin America, had cautioned against the invasion on grounds that the mission was unclear.

What possible military threat could Grenada pose to the United States? Was the mission about rescuing the medical students? Restoring law and order? Regime change? Evacuating supposed hostages and saving U.S. lives? Stopping the airport from being built? Ridding the island of Cuban influence? Or, perhaps the most far-fetched, “pre-emptive self-defense”? Moreover, couldn’t any of these goals have been addressed by non-military means? If the United States genuinely believed the medical students were at risk, why not just evacuate them, as the Pentagon had advised? And even if a military solution were warranted, how could an island of 100,000 people possibly require 7,000 troops with another 20,000 stationed just offshore?

The real reasons for the invasion lay elsewhere. After the humiliating U.S. defeat in its protracted war against Vietnam, military morale and public sympathy for the military were low. As several U.S. government sources admitted, Washington sought to salvage its credibility as a superpower and to restore public support for the troops, in part to justify the near doubling of the military budget between 1980 and 1985 amid U.S. interference in Central America. A short, resounding military victory offered an answer. The invasion of Grenada was theater, pure and simple. Tiny Grenada became the shiny button that held together the fraying military uniform of a superpower, the glistening medal that reflected back to the United States its military might. (In fact, the United States awarded over 19,000 medals for the mission.)

The need for muscle-flexing also helps explain why the United States fobbed off Grenada’s requests for aid in 1979 with an offer of $5,000 yet chose to spend $134 million on the invasion and another $157 million in aid to Grenada in the five years following. The United States also went on to complete the very airport it had so opposed being built. How resonant are the words of the late Jamaican dub poet Jean “Binta” Breeze: “Aid travels with a bomb, watch out!”

Today, the invasion of Grenada stands as a reminder that the Cold War was only cold for the superpowers. It was scaldingly hot in many smaller places around the globe.

Read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time.

Shalini Puri is professor at the University of Pittsburgh. She is the author of The Grenada Revolution in the Caribbean Present: Operation Urgent Memory and maintains the website urgentmemory.com. With Lara Putnam, she co-edited Caribbean Military Encounters. Her current research is on Caribbean poetics for freshwater justice.