This article is copublished with A dónde van los desaparecidos. Leer el artículo en español.

After his father died, Denis Munguía decided to migrate from his home in Honduras to the United States, where he planned to work in Alabama and send money home to support his family. “He was really happy to come here and help out his mother,” recalled his friend Ana, who worked with Denis as a teacher before she, too, migrated. Denis stayed in touch with friends and family during the arduous journey across Central America and Mexico. On August 2, 2022, close to midnight, he sent a message letting them know he had reached a safe place. No one has heard from him since.

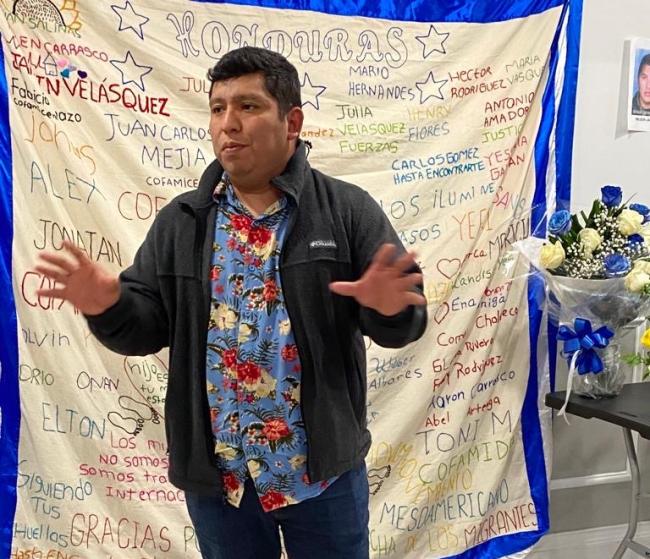

On a Sunday in October 2023, outside El Buen Pastor Episcopal Church in Durham, North Carolina, Ana shared the story of her missing colleague, thanks to an invitation from the Mexican human rights activist Rubén Figueroa. As the parishioners, nearly all of them Latino immigrants, ate pozole in the basement after the church service, Rubén, a stocky man in his 40s with a stolid presence, invited them to participate in a project to honor their friends and family who disappeared on the migrant trail.

As part of the Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano, Rubén spent more than a decade searching Central America and Mexico for migrants who went missing on their way to the United States. Then his brother disappeared in Playa del Carmen, the resort town on the Yucatán peninsula currently facing a wave of violence. Facing threats at home in Mexico, Rubén was forced to flee.

Now living in exile in North Carolina, the human rights activist continues the work he began south of the border, this time armed with a bag of colorful thread, needles, and a large cotton cloth: the manta de la memoria, the memory blanket. Rubén invites his fellow immigrants to embroider the names of their relatives who never reached their destinations.

As she recalled her friend, Ana traced Denis’s name on the cloth. She crossed Mexico three times before reaching the United States, and she grew intimately acquainted with the trials of the journey north: deportation, hours stuck in an airless trailer in Veracruz, fear for the worst. “Once I arrived, it took me months to wake up and know I was in a safe place,” she says.

After sending that message in August 2022, Denis became one of thousands of migrants who have gone missing on their way north. According to the Missing Migrants Project, 9,528 migrants have disappeared or died in the Americas since 2014, including more than 5,000 along the U.S.-Mexico border. Data collected by the group No More Deaths suggests a rising rate of migrant fatalities along the southwest U.S. border, and Mexico’s forensic crisis continues unabated. Human rights groups have warned that the Biden administration’s new executive order restricting access to asylum will push border crossers to resort to more deadly desert routes.

Yet even within the pro-migrant movement in the United States, few talk about those who never arrive. The movement focuses, understandably, on fighting for the rights of those who already managed to cross the border. The memory blanket is a first step to start a conversation about missing migrants in the United States—to name them, remember them, and build a movement to find them.

“I think there’s a moral responsibility to not forget,” Rubén says, “so that all the triumphs of the pro-migrant struggle in the U.S. can be in memory and honor of those who didn’t arrive.”

Folded alongside the unfinished memory cloth, Rubén stores two others like it, both covered with names. They represent a decades-long struggle that began with the Central American mothers who pioneered search efforts for missing migrants. One of the blankets traveled through Guatemala, where mothers from the Asociación de Familiares de Migrantes Desaparecidos in Guatemala embroidered the names of their disappeared relatives. Another, lined in blue and white, accompanied Rubén on one of his last trips to Honduras. One more remains in El Salvador.

Searching Central America and Mexico

Rubén grew up in the town of San Manuel, Tabasco, where he watched Central American migrants pass through on the cargo train known as La Bestia, the beast, long one of the primary routes taken to cross Mexico. He recalls seeing them with indifference until he spent a season working undocumented in the United States in 2005. When he returned, the men who risked their lives on the railways reminded him of his friends. “Because I’d spent time with a lot of people who managed to get to the United States, and I knew a little bit of the suffering they went through, when I saw the train after I returned, I said, I should do something, at least in my community,” he remembers. Along with his mother and some friends, he began offering food to the train-hoppers. The word spread, and when migrants showed up in town, locals sent them to the Figueroa home: “Go to Rubén and his mother’s place, and they’ll help you out.”

A few years into that work, an Amnesty International mission came through town to document the abuses faced both by migrants and the civilians who helped them out. The organization invited Rubén to the presentation of their report in Mexico City, where he met Marta Sánchez Soler, the coordinator of the Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano. She invited him to be part of the movement, accompanying mothers searching for their disappeared children.

“We would get to a town, after notifying through a community radio or a church that we’d be in the community,” he recalls of the work in Central America. “We invited people with disappeared relatives to come to the plaza so we could document their case.” In each town, the movement found cases of people who had lost all contact with their families after leaving for the United States. They gathered the families’ clues—a last phone call, a location—and looked for their disappeared relatives along the migrant trail. Sometimes the prodigal sons and daughters appeared alive; sometimes their remains turned up in a forensic clinic.

The movement also organized the Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants. Central American mothers traveled across Mexico in one of the first organized search efforts in the country, before the disappearance crisis in Mexico grew visible among the general population. “Central American mothers were one of the least-heard groups when it comes to the disappeared,” Rubén says. “They were always a step ahead, creating the path, making the way.”

Along the way, they found migrants who had settled in Mexico and lost contact with families in Central America. The Puentes de Esperanza project was born, a sort of reverse search effort: after documenting a half-dozen cases, they sought out the migrants’ families to tell them that their sons and daughters were alive.

After 15 years in the movement, Rubén found himself in the position of the mothers he had long accompanied. In June 2020, his own brother, Freddy Díaz Figueroa, was disappeared, along with two other people in Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, where he had moved to work.

Because of the risks he faced from both organized crime and the state, because of his brother’s disappearance and his human rights activism, Rubén sought asylum in the United States. There, far from his family home in Tabasco, he mourned. Depression overtook him. He knew it was unlikely that his brother was still alive. At times, he couldn’t believe what had happened: after so many years of walking with the relatives of disappearance victims, he had become one of them.

In August 2022, Rubén reported a clandestine grave in Quintana Roo that he suspected contained his brother’s remains. Local authorities initially denied that the site was of interest, insisting that it was just “a cave with bones,” though they didn’t know how the remains had gotten there.

This May, the federal prosecutor’s office notified Rubén of DNA results that identified Freddy as one of the seven bodies found at that spot. As of late June, Rubén and his family were still waiting for Freddy’s remains to be sent home.

Three suspects thought to be involved in the crime are currently in custody. Although they were arrested for charges unrelated to Freddy’s disappearance, they are currently the primary suspects in the case. “We hope that a process will begin against them soon,” Rubén says, “and that, if they are guilty, they will be sentenced according to the law.”

Mourning from Afar

In the United States, looking for missing people doesn’t pose the same dangers—political persecution, threats, violence—as in Mexico and Central America. But the precarity of life as a recent immigrant makes it difficult for families to start the process. Long working hours mean that, as Rubén puts it, “you don’t even have time to sit down and cry or think about your disappeared relative, not because you don’t love them or you forgot them, but because life itself is that busy.”

Undocumented families face the possibility of deportation if they approach the border region. Traveling is more expensive, and searching requires crossing large distances. Rubén can’t just pack a backpack and get on a bus. The routes aren’t as clear. It took years of work to build a network of organizations and family committees across Central America. No such infrastructure exists in the United States. A few groups, among them the Águilas del Desierto in Arizona and the Armadillos in Tijuana and San Diego, comb the desert for recently disappeared migrants, but looking for people who went missing two or five or 10 years ago implies a different kind of organization.

Under such adverse conditions, the blanket represents the beginning of a longer process. Since Rubén began the memory cloth project in the summer of 2023, immigrants in North Carolina, Virginia, California, and New York have added their loved ones’ names to the blanket. After presenting the blanket at the Buen Pastor church, Rubén parked at a Durham apartment complex and set up a folding chair next to a shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe. It was a late Sunday afternoon, and a few of the neighbors, mostly recently arrived immigrants, were out and about. Rubén and his wife filled in a few unfinished names, occasionally greeting passersby and explaining the project.

For some mothers, the blanket provides a chance to talk about their missing children for the first time. For others, it represents a continuation of an ongoing effort. Reyna Portillo searched for years alongside Rubén for her son Marvin Leonel Álvarez Portillo as part of the Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants. Then she, too, migrated from her home of El Salvador. Rubén visited her in Virginia, where she stitched her son’s name in red thread.

In California, Rubén took the blanket to Susana, whose son Daniel disappeared crossing the border three years ago while on his way to meet her. Rubén documented her case and she, too, left Daniel’s name on the cloth.

“We Can Embroider Their Names”

Once the tapestry is filled with names, Rubén plans to present it at the border wall. People vanish while migrating because of policies, whether in their hometowns or the lands they transit or their destination.

“When migration policies change, the number of missing people changes,” Rubén explains. Recently, he has documented cases of people who disappeared after being deported under Title 42, the pandemic-era policy that Donald Trump established in March 2020. The restriction, struck down in May 2023, allowed border officials to automatically turn away asylum seekers on public health grounds. “They got to the border, requested asylum and were deported,” Rubén says. “Then they tried to cross without turning themselves in, and they disappeared. It’s a direct impact.”

The problem transcends continents. As people are increasingly on the move in response to violence, political and economic instability, and climate change, migrants disappear crossing lands all over the Americas—in the desert of northern Mexico and, increasingly, the jungle of the Darien Gap—but also in boats crossing the Caribbean and from North Africa to Europe.

“The idea is to encounter each other through the manta de la memoria, organize, and create an international committee of families of the disappeared,” Rubén says. “Central American mothers who can embrace the mothers from Algeria, the mothers from Tunis, mothers and families of disappeared migrants all over the world.”

At his home in Durham, Rubén’s apartment opens onto a lawn shared with neighbors from Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. His daughter plays with children from Honduras and Afghanistan. On a Sunday afternoon, as Rubén unfurls the blankets over the patio, a gaggle of young boys with a soccer ball approaches, curious about the unusual activity.

“Who here is from Honduras?” Rubén asks. They shout in excited recognition, and Rubén explains that the embroidery represents migrants who went missing on the way north. “Why do you write down the names?” one asks. “So we don’t forget them,” Rubén explains.

“I have an uncle who got lost in the…what’s it called? The deserts. He got lost like five months ago,” one of them volunteers.

“Then we can embroider his name, and we can also tell an organization that looks for migrants so they can search for him,” Rubén says. “You can tell your mom or your dad, and if you come to play soccer, you can bring his name on a piece of paper, and we’ll embroider it.”

Madeleine Wattenbarger is an independent journalist based in Mexico City.