Nora Rosatti listens attentively to Lileia Almeida as she speaks inside the packed wood and straw oypysy (temple) in the reclaimed ancestral territory of Laranjeira Nhanderu in southern Brazil. The two women are both from the Guarani family of Indigenous peoples, but belong to groups on opposite sides of the international border between Brazil and Paraguay. Almeida, a young Laranjeira Nhanderu leader, recounts experiences of resistance and danger at the retomada, a reoccupation of territories by families of the Kaiowá Indigenous people in Brazil’s state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

“Our struggle is incredibly difficult. You must be very strong and very wise to fight for the land and territory,” says Almeida.

Almeida speaks of the Kaiowá’s decades-long battle against the incursion of state-backed agribusiness and colonization, a process that saw her people confined to tiny reservations. Left with only a small fraction of their ancestral territory, they have suffered widespread poverty and fierce cultural, social, and economic challenges.

Rosatti nods in understanding. She is a leader of the Paĩ Tavyterã, an Indigenous people concentrated less than 100 kilometers away, in the Paraguayan administrative department of Amambay. The Paĩ Tavyterã share many cultural, linguistic, and blood connections with the Kaiowá; they are often considered branches of a single Indigenous people.

In turn, the Paĩ Tavyterã share experiences of enduring the devastating damage produced by the incursion of agribusiness and extractivist industries in their territories. In spite of a 2004 Zero Deforestation Law, Amambay saw a 41 percent decrease in its remaining native forests from 2002 to 2021 as industries such as cattle ranching expanded. This dynamic has placed enormous pressure on Indigenous land and ways of life.

Faced with these similar but nuanced situations, the Paĩ Tavyterã and the Kaiowá are engaging in meetings to deepen bonds to mutually strengthen their territorial struggles.

Retaking Territory

Rosatti, along with three other Paĩ Tavyterã leaders, crossed the border at the end of January to join Kaiowá leaders, teachers, and students from the Intercultural Indigenous Faculty (FAIND) of the Federal University of Greater Dourados (UFGD) in the activities of Guarani-Kaiowá Week, organized by the UFGD and the University of Cardiff in the United Kingdom. A member of the Guarani people of Bolivia also participated.

Despite having close cultural and blood links to the Kaiowá, Rosatti visited Brazil for the first time in late 2022. Sofía Espíndola, a researcher who works alongside the Paĩ Tavyterã through the cultural, environmental, and research activities of the NGO Ary Ojeasojavo, says that contact is limited by financial barriers to travel.

“It’s vital for the bonds to be reinforced,” says Espíndola. “They share so much, and those commonalities allow for a deep understanding of the contexts in which they live.”

The territories of Guarani peoples historically stretched over an enormous area of South America, reaching parts of modern day Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and Uruguay. Six Guarani peoples live in present-day Paraguay, and a Guarani tongue —Paraguayan Guarani— is spoken by 70 percent of the national population. There are three Guarani peoples in southern Brazil making up a population of some 51,000 individuals. The Kaiowá, a name derived from Guarani for “people of the forest,” are the second largest Indigenous group in the country.

Conversation in the oypysy of Laranjeira Nhanderu takes place in regional variations of the Guarani tongue shared by the two groups. While the Paĩ Tavyterã pepper their Guarani with loan words from Spanish, the Kaiowá do so with terms from Portuguese.

Kaiowá speakers explain that, in response to the lack of state action regarding their need to recover territory, they have adopted the tactic of retomadas, the retaking of ancestral land through physical occupation.

“Retomadas are a way of recovering our natural resources like forests, medicinal plants, and animals to survive and strengthen our culture, our tekoha (territory),” says Luis Carlos, a Kaiowá teacher. “So much has been stolen from us by the karai, the white people, the colonizers.”

The enormous loss of territory suffered by the Kaiowá has led to widespread conditions of extreme poverty and violence. According to Earthsight, Mato Grosso do Sul has the country’s highest murder and suicide rate of Indigenous people, and 30 percent of conflicts related to Indigenous land are concentrated in the state.

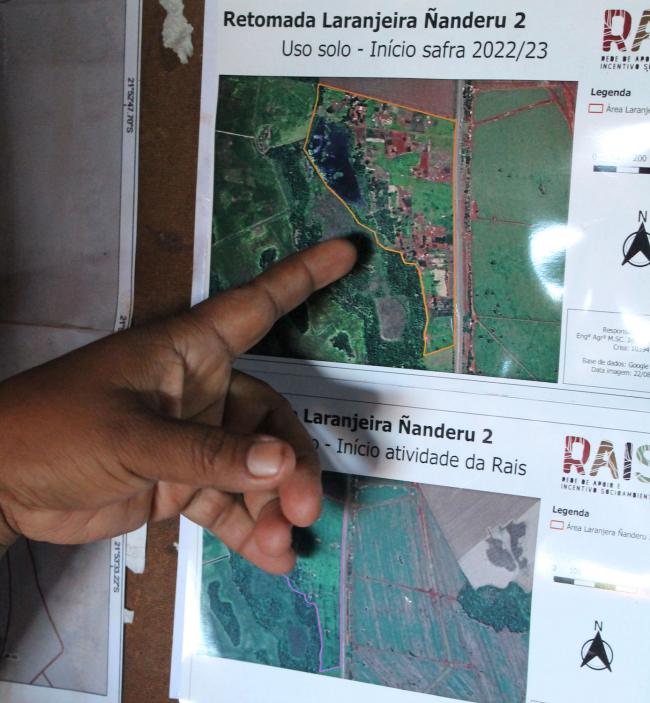

At Laranjeira Nhanderu, 35 Kaiowá families have retaken part of a soy farm established on ancestral territory. Almeida states that they are extremely close to having the land officially demarcated, an administrative process to legally recognize Indigenous land rights over an area. This success story is far from common: retomadas have often been met by violence from land usurpers with state support, including the 2022 murder of Kaiowá man Vitor Fernandes by military police in the retomada of Guapoy.

Dr. Antonio Ioris, a geographer accompanying the Kaiowá, says that Brazil’s Indigenous peoples are legally guaranteed the rights to their ancestral land. In practice, however, demarcation of this land is rare and torturously slow. He explains that the fact that usurpers receive no compensation payment when land is returned to Indigenous peoples can complicate the process.

“In theory it should make it easier; it should be easier to evict them, but in fact it’s much more difficult. Because the farmer will fight nail and tooth,” he says. “There haven’t been that many victories.”

In contrast to the agonizing process endured by Indigenous communities, a 2020 policy of the anti-Indigenous government of Jair Bolsonaro allowed for the registration of 58,000 hectares of private farmland located in Indigenous territory in the process of being demarcated in Mato Grosso do Sul. Mongabay reports that 20 of the 26 areas of Indigenous land in the process of demarcation in the state were impacted.

The recent creation of a Brazilian Ministry of Indigenous Peoples under the new government of Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva provides some hope of change to the dire situation faced by Indigenous peoples like the Kaiowá.

On March 3, the families of Laranjeira Nhanderu retook a further part of their ancestral territory, an action mentioned as an objective during the January visit. The military police immediately arrived at the retomada and threatened to carry out an eviction without a permit, according to reports. The community put out a call for support to guarantee their rights and avoid further violence.

Invasions and Resistance

The following day, an intercultural conference took place at the FAIND on the UFGD campus on the outskirts of Dourados. The hall filled with Kaiowá students and people affiliated with the Indigenous institution, which is a vital resource in a country where Indigenous people are four times less likely to go to university than non-indigenous people. There are no intercultural Indigenous faculties at Paraguayan institutions of higher-education.

Rosatti and fellow leader Andrés Brítez spoke of the severe land problems facing their own community Yvy Pyte across the border. Yvy Pyte is at the center of the pressures produced by land grabbing in Amambay. It is one of the few islands of native forest surviving amid the endless grass plains created over recent decades by the ranching industry.

“We are from here; we were born here. My grandfather, and his grandfather, and his grandfather lived here,” Rosatti says during a visit to the community days before Guarani-Kaiowá Week. “The land is ours. The stream, the trees, plants, the forest; all of nature is a vital part of our land.”

She was speaking in the central clearing of Yvy Pyte. Jasuka Venda, the sacred hill considered by both Paĩ Tavyterã and Kaiowá as the place in which the world was created, stood as a forested backdrop behind the community’s oypysy.

This sacred mount, along with many Paĩ Tavyterã communities, faces intense danger from the incursion of armed groups. Drug planters and smugglers operate in the area, as do the Paraguayan People’s Army (EPP) illegal armed movement and the special unit of state forces created to combat it. On October 23 of last year, two Paĩ Tavyterã men were killed at one of the entrances to Jasuka Venda; official sources attributed the deaths to the EPP.

The ancestral site became a point of enormous interest for the Kaiowá during the aty guasu (assembly) in the FAIND. Many have had few opportunities for contact with Jasuka Venda; students enquired about the current state of the hill and the origins of its name, which recalls the site of the energy (jasuka) in which the creator god Ñane Ramõi Jusu Papa created himself and the world. At the aty guasu, Brítez explains that his community has been pressuring state institutions for decades to issue titles for their land. Of the community’s 11,313 hectares, approximately 4,000 hectares do not have titles.

This lack of legal protection makes their land incredibly vulnerable to invasion. Three large invasions have taken place since December 2022, with armed groups entering by force to cut down native trees. One invader, named as Ramón Segovia, is now attempting to sell 1,920 hectares of their land.

“We’re running out of ideas after so many years of struggle. The latest invasions have been enormous and especially tiring for us,” says Brítez. “Without tekoha (territory), there can be no teko (way of being).”

A 2015 UN report states that 134 of Paraguay’s almost 500 Indigenous communities are landless and another 145 are facing land possession issues, such as ownership disputes with private entities.

Indigenous land problems have intensified further since September 2021, when a law was pushed through Congress by legislators closely allied with the powerful and land-hungry agribusiness sector; the law criminalizes land defense efforts and facilitates evictions of Indigenous and campesino communities during land conflicts. Eleven Indigenous communities were evicted from their lands by state forces from November 2021 to October 2022, according to the social research organization Base Investigaciones Sociales.

Faced with the unresponsiveness of state institutions, the Paĩ Tavyterã of Yvy Pyte have looked to implement their own solutions, such as a creating a detailed map of their territory produced using Brítez’s ancestral knowledge. Representatives of the University of Cardiff have said that they will digitize the map.

Cross-Border Contrasts

In the build-up to the Guarani-Kaiowá gathering in Brazil, a meeting of Paĩ Tavyterã leaders took place in the community of Ita Guasu.

Luis Arce, leader of Ita Guasu, explained that the Paĩ Tavyterã and the Kaiowá were historically one and the same. He said his own father was Kaiowá, and that differences between the two peoples had been produced by a history of invasion and arbitrary political borders. A devastating upheaval in the Indigenous territories of the region was produced by border changes and sales of enormous amounts of land to yerba mate companies in the aftermath of the Triple Alliance War (1864-1870), fought between Paraguay and an alliance between Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil.

The leaders analyzed the retomadas used by the Kaiowá to reclaim their territories, tactics that are so different from their own. Leader Gregorio Morrilla expressed curiosity regarding the safety and effectiveness of the retomadas and expressed a desire to meet with the Kaiowá to learn more.

Sofía Espíndola said that the great difference between Paĩ Tavyterã and Kaiowá tactics was due to the much earlier arrival of agribusiness in Mato Grosso do Sul than in Amambay, and reflected broader social contexts in Paraguay and Brazil.

“The Kaiowá have close relations with the Brazilian campesino movement and other social movements who employ the strategy of occupying land,” says Espíndola. “Social movements in Brazil weren’t debilitated in the same way that they were in Paraguay; here they were wiped out during the dictatorship. People tend to stick to established legal procedures in Amambay, but in Brazil there is a strong movement to defend the land more actively.”

Strengthening Ties

The exchange between Guarani peoples culminated in the university halls of the FAIND. Dr. Eliel Benites, Kaiowá and director of the institution, cited the importance of intercultural education at FAIND, where classes are given in Guarani, as a key tool for collective reinforcing of territory and culture.

“The task of the new generations, the academics, professors, students, children is to rebuild our tekoha. A new tekoha: one more strongly rooted in the memories of our ancestors and our elders, without losing sight of the future,” he said.

This commitment to intercultural reconstruction was strengthened by the university’s rector Dr. Jones Dari Goettert, who said UFGD would visit and provide scholarships to Paĩ Tavyterã youth to study at FAIND.

Both Paĩ Tavyterã and Kaiowá leaders, alongside the organizations involved in the Guarani-Kaiowá Week, agreed to continue carrying out meetings and to begin implementing cross-border cultural, environmental, and advocacy initiatives in Guarani communities.

Paĩ Tavyterã leader Brítez reflected on the gathering: “The experience has been useful so that our Kaiowá brothers and sisters can learn about and help to analyze what is happening to us. We must tighten our bonds so that we learn more about our different situations and support each other.”

The day ended with a Kaiowá circular ceremonial dance. The Paĩ Tavyterã leaders were tentative in participating at first, saying that the dance, though similar to their own, had many differences. However, within a matter of minutes, Nora Rosatti took the lead and produced a fusion of her own Paĩ Tavyterã call-and-response chants with the Kaiowá dance steps.

William Costa is a freelance journalist based in Asunción, Paraguay. He concentrates on social, environmental, and cultural topics. He has written about issues involving Indigenous peoples in Paraguay for Paraguayan outlets like E’a and Hína and international outlets like The Guardian and Al Jazeera. He was corecipient of a 2020 Amnesty International Paraguay journalism prize for work on Indigenous experiences during the pandemic.