The November 15 demonstration calling for the release of political prisoners in Cuba was announced on September 20. While it is unclear what form the protest will take, its mere announcement has provoked strong responses both within and without Cuba. In the United States, the government and much of the corporate media condemned the Cuban government for refusing to give demonstrators a permit. The U.S. government also threatened to increase sanctions. The Cuban government, in turn, accused the United States of funding and organizing the march to foment a regime change.

On July 11, widespread protests in Cuba provoked similar debate. Some Cuba experts denounced the Left for idealizing the Cuban Revolution and ignoring or downplaying the Cuban government’s authoritarianism. The Black Lives Matter’s statement supporting the Cuban government is an example that epitomizes this “leftist” response. These experts, who argue that supporting the Cuban government is an unjustifiable stance regardless of U.S. policy, will likely react similarly to the aftermath of the November 15 demonstrations.

The critiques levied at leftists in the wake of the J-11 protests assumed statements like the BLM Instagram post to be far-reaching and influential. Yet mostly absent from these critiques was any recognition of the actual influence that leftwing groups exert on U.S. corporate media coverage of Cuba. As a result of their massive resources and outreach, both on social media and through traditional news channels, U.S. corporate media largely set the terms of political debate over U.S. foreign policy by shaping how U.S. and international audiences and politicians perceive the Cuban government’s actions.

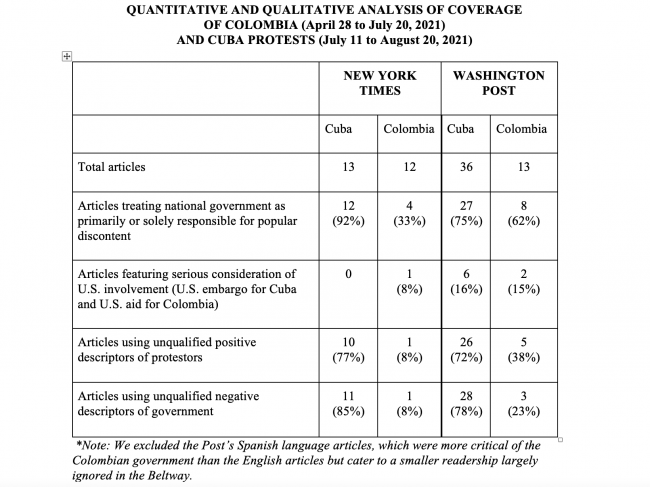

To see whether these leftist groups exerted any discernible influence on U.S. media coverage of J-11, we examined the coverage of the protests in Cuba that began on July 11 and the protests in Colombia that erupted ten weeks before on April 28. In The Washington Post and The New York Times, that coverage included 74 news stories, op-eds, and editorials. We chose these two papers because they are two of the most influential U.S. newspapers and have a reputation as “liberal” media. Conservatives often claim that these newspapers cover U.S. enemies like Cuba more favorably than U.S. allies like Colombia and equate them to the leftist groups that many Cuba experts have denounced.

This study examined the coverage of the protests in Colombia and Cuba in the two newspapers during a period of six to eight weeks from the day that the protests broke out in each country. The table below displays the quantitative and qualitative results of our analysis.

Worthy vs. Unworthy Protesters

Our analysis shows that the two papers covered the protests in Cuba far more negatively than Colombia. They closely match the results from the book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media by Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman, which uses the terms “worthy” and “unworthy” to describe victims of violence in U.S. allied and enemy states, respectively. Chomsky and Herman argued that in the liberal U.S. media, “worthy victims [in enemy states] will be featured prominently and dramatically, that they will be humanized, and that their victimization will receive the detail and context in story construction that will generate reader interest and sympathetic emotion. In contrast, unworthy victims [in allied states] will merit only slight detail, minimal humanization, and little context that will excite and enrage.”

Although people in both countries protested for many of the same reasons—inequality, poverty, and unemployment exacerbated by Covid-19; rising cost of living; police violence; and systemic racism—the Colombian protests lasted far longer and were met with a harsher crackdown than in Cuba. According to respected human rights and civil society groups, the death toll ranged from 21 to 44 deaths in Colombia in a population of 51 million and one to five deaths in Cuba in a population of 11 million. In addition to disproportionately killing more people, Colombian police also injured protesters more severely than their Cuban counterparts, such as deliberately shooting at dozens of protesters’ eyes.

The difficulties that organizers in each country faced also differed. Freedom House is a conservative analyst that ranks countries’ degree of internal freedom based on “access to political rights and civil liberties” (though it ignores the social, economic, and cultural rights also enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights). According to their rankings, it is generally easier to protest in Colombia because it is “partly free” compared with “not free” Cuba. But it should be noted that the Cuban government restricts dissent in the face of real and perceived U.S. external subversion while much of Colombia’s U.S.-funded and trained security forces, a remnant of decades of civil conflict, wage war against real and perceived internal threats. As a Colombian graduate student of Latin American history at Stanford University commented, “for dozens of protesters to be killed in a ‘democracy’ is incredible.”

President Biden did not agree with this student’s sentiment. Ten weeks into the continuing crackdown in Colombia, Biden had not even threatened to suspend any portion of the $460 million in U.S. aid earmarked for Colombia for fiscal year 2021. But just one day after J-11, Biden not only condemned the Cuban government, but also strengthened sanctions against it. Biden’s decision came after the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly condemned the U.S. embargo in a lopsided 184 to 2 vote on June 23. The United States and Israel were the only countries who voted against, and three countries—Brazil, Ukraine, and Colombia—abstained.

Coverage by The Post and The Times largely conformed to Biden’s foreign policy agenda. The protests in Colombia persisted for five days before either paper started covering them, even as fatalities mounted from the violent police crackdown. Coverage on Cuba began within hours after protests started. And even though Colombia’s population is more than four times larger than Cuba’s and the country is of far greater economic importance to the United States, the protests in Cuba garnered disproportionate attention: 13 articles for Cuba versus 12 for Colombia in The New York Times and 36 articles for Cuba versus only 13 for Colombia in The Washington Post.

Qualitatively, there was also a marked difference. News coverage and commentary in both papers used far more positive descriptors without qualification for Cuban protesters, including “brave,” “fearless,” “courageous,” “oppressed,” “peaceful,” “asking/yearning/fighting for freedom,” and “pro-democracy.” Nearly all articles expressed solidarity with the protesters, including news pieces, such as with the headline “‘The Spark has been Lit’: Cuban Dissidents Feel Emboldened Despite Crackdown."

In contrast, the descriptors for the Cuban government were nearly all negative across article types, including “authoritarian,” “draconian,” “autocratic,” “dictatorship,” “repressive,” “thuggish,” “totalitarian,” and “police state.” The Times headlined a news article "'Terror’: Crackdown After Protests Sends Chilling Message," while The Post headlined an op-ed “As in 1994, Cubans protest against a regime’s mortal threat.” No article in either paper used strong descriptors like “terror” and “mortal threat” for the Colombian government.

Additionally, while the national government controls the police in both countries, only the Cuban police were treated as representative of the government’s attitude towards its citizens. In Colombia, the police were portrayed as out of the government’s control, like in The Post headline “Colombia’s police are cracking down on protests. That may be backfiring.”

By making a misleading distinction between the Colombian government and the police, most news stories and commentaries attributed much less responsibility to the country’s government around the Colombian protests. Indeed, the news media was much quicker to blame enemy Cuba than U.S. allied Colombia, despite the harsher crackdown on protestors. We should note, however, that the disparity for this criterion was far wider in The Times (92 percent for Cuba vs. 33 percent for Colombia) than in The Post (75 percent for Cuba vs. 63 percent for Colombia).

Ignoring and Downplaying U.S. Involvement

Another important criterion in the investigation was examining how the papers described U.S. policy toward the two countries. For Cuba, when authors bothered to mention the U.S. embargo, they usually dismissed it as a secondary cause of the protests or as Cuban government propaganda seeking to deflect attention from state actions that contributed to the popular discontent. Neither paper published a piece that assessed the merits of the Cuban government’s claim that U.S. sanctions exacerbating the social and economic effects of Covid-19 were the principal cause of the protests.

The Post’s and Times’s coverage of Colombia mostly overlooked any U.S. involvement. With the notable exception of one op-ed published in The Post, few articles and commentaries mentioned, let alone independently investigated, the well-documented fact that decades-long U.S. military aid and training have contributed to human rights violations by the Colombian government. One news article in The Post headlined “Duque’s repressive security forces have failed Colombia'' even erroneously suggested that U.S. aid had improved Colombia’s police conduct for a time.

In reality, the difference between U.S. conservative and liberal news coverage of Cuba is one of degree, not of kind, because both unquestioningly uphold U.S. foreign policy imperatives.

While neither the Cuban government nor its international supporters are beyond reproach, denouncing them while ignoring or downplaying the extreme imbalance in power and influence between the Cuban and U.S. governments and media—both liberal and conservative--does nothing to help Cuban dissidents within Cuba.

Mikael Wolfe is Assistant Professor of History at Stanford University. His current book project is titled Rebellious Climates: How Extreme Weather Shaped the Cuban Revolution.

Jessica Femenias is a BA Student in History and Philosophy at Stanford.