Originally published in Spanish by Nueva Sociedad.

Translated by Liza Schmidt.

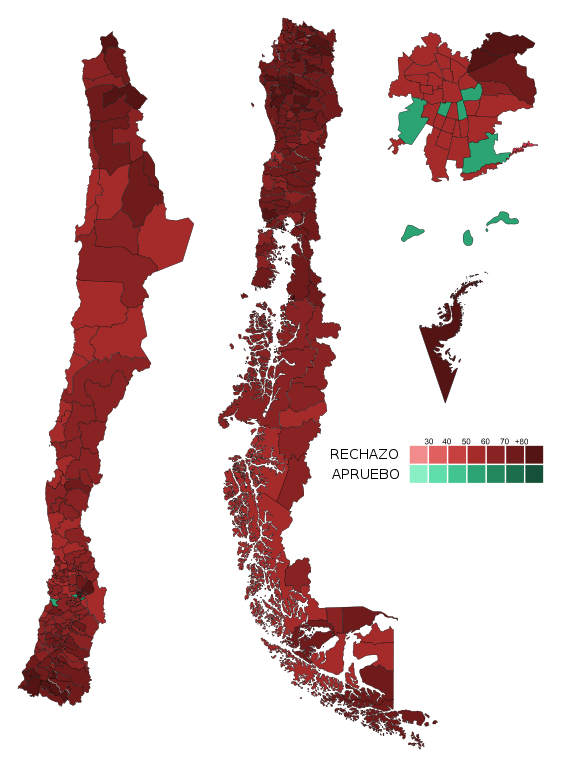

What one year ago seemed like it would be a formality to ratify the constitutional process ended up being a crushing defeat for progressive Chilean forces. The Rechazo (reject) vote beat the Apruebo (approve) vote by nearly 25 percentage points in a referendum with mandatory voting—in contrast to recent elections—and record turnout. Rechazo groups celebrated the win against “revanchism” and “radical Octoberism” (a reference to the 2019 uprising) and a constitution they considered “refoundational” and contrary to “the soul of Chile” and “Chileans’ common sense.”

How did a process that began with a historic level of support end up so truncated? What happened to the support for the constitutional process?

This constitutional process began on November 15, 2019. As a result of a massive social uprising in October that year, Chilean political parties across the political spectrum reached an agreement, setting a timeline for drafting a new constitution. The first milestone in this timeline was a plebiscite in which the overwhelming majority—more than 78 percent—of Chileans voted to replace the existing constitution and elect a Convention responsible for the rewriting. These results were truly impressive, not just for the high percentage but also for the geographic distribution of votes. Just five of the country’s 346 comunas (municipalities) voted against the constitutional process. These five municipalities included the three iconic Santiago comunas where the national economic elite reside. Many rushed to point out how the results indicated that the country was not polarized between the right and the left but that the real division was between the pueblo (people) and the elite. This image of a homogeneous pueblo clashing with the elite crystallized in references to “the three comunas,” which became part of the common lexicon in political discussions.

Agreements in Congress guaranteed that the Constitutional Convention would be made up of an equal number of men and women, with quotas for Indigenous peoples, and, in keeping with the fierce anti-party sentiments of the October 2019 protests, with opportunities for independent candidates. Specifically, candidates with no party affiliation were allowed to form independent slates, like candidates of traditional parties.

The election of the Convention members was a blow to those who hoped for a return to pre-uprising politics. The two traditionally powerful political coalitions had meager results. The right received a paltry 20 percent of votes, leaving it far from reaching the third of Convention members required for potential veto power. The center-left coalition saw its center and more moderate forces collapse. Perhaps the most well-known example of this crisis was the Democracia Cristiana, which only managed to elect one member—the party president—to the Convention. But by far, the greatest accomplishment of these elections was the resounding success of the independents associated with the 2019 protest movement. Of the 155 members of the Constitutional Convention, 103 had no traditional political affiliation. Thus, the final composition of the Convention had a clear majority representation from progessive sectors, especially new political forces that had emerged from the social uprising raising the banners of feminism, Indigenous rights, and a strong anti-elite discourse.

Public excitement at the beginning of the process ran very high: when describing what they felt about the process, 52 percent named “hope” as the primary emotion, followed by “happiness” with 46 percent. So what happened to this 78 percent support and the hope and happiness regarding the process? Progressive and leftist forces will likely spend the next few years trying to answer that question.

Preliminary Reasons for the Defeat

As more data becomes available and the debate advances, a closer analysis of what happened will develop. For now, there are three reasons that stand out as explanations for the September 4 outcome: 1) The rejection of the politics of performance in the Convention; 2) The association of the Convention with traditional politics; 3) The reaction of traditional identities to the power that marginalized identities held in the process.

One of the issues that dominated the debate was the politics of “performance” in the Convention. Before long, the Constitutional Convention began to lose support, especially among right-wing voters who were wary of it as a kind of caucus of activists for progressive causes. If for activists stopping mobilizations, even from within the halls of power, was a betrayal, then for some voters, especially those who value order, unending mobilization was a nightmare.

Several Convention members achieved fame and social legitimacy for their street performances, which included costumes and provocative declarations about aspects of traditional identities. These street protests often denounced the authorities with shouts and chants. However, the same attitudes that were perceived in the streets as defiance, were seen within the Convention and from the seats of power in another light. In addition, the ethos of social mobilization that persisted in the Convention tainted many of its actions with a testimonial sentiment. For some members, it was important to present maximalist, bold, and symbolic proposals, even though they did not have the votes to be approved. For example, one member proposed dissolving all the powers of the state and replacing them with assembly-style bodies. The media amplified these performative acts and unreasonable proposals, which were also highlighted by disinformation campaigns on social media. Videos of these declarations also frequently appeared in the Rechazo campaign and TV programming. What in the beginning appeared bold and beautiful ended up creating uneasiness.

The association of Convention politics with traditional politics occurred in the context of a strong push for radical and anti-establishment politics. According to the Center for Public Studies, the percentage of the population that identified with a specific party fell from 53 percent in 2006 to 19 percent in 2019. Moreover, some studies have indicated that a significant portion—12.9 percent—of the population has taken on a position against the “traditional” parties as their primary identity. The strength of the Convention was that, in the beginning, it was seen as distinct from traditional politics.

It is possible that, ironically, the Convention’s performance politics and testimonial squabbles actually resembled Congress and traditional politics, where these practices also abound. In any case, the use and abuse of these practices did not help Convention members appear any more effective than traditional politicians at reaching agreements and carrying out citizen demands . Meanwhile, amid the constitutional process, there was a presidential election and a change in government. The new administration, particularly former congressional representative Gabriel Boric, was closely associated with the genesis of the constitutional process. Thus, opposing the constitutional process became a form of opposing the new government, and part of the energy against political institutions shifted to the Rechazo side.

The reaction of traditional identities especially pertains to the first article of the draft constitution, which enshrined Chile as a “social and democratic state with rule of law,” which is also “plurinational, intercultural, and ecological.” Together with the definition of Chile as plurinational, the article recognized collective rights for Indigenous peoples and would have installed an Indigenous justice system.

The most cited reason for rejecting the draft constitution was the negative view of Convention members, followed by the issue of plurinationality. After the draft constitution was presented, the plurinational state and the creation of an Indigenous justice system were the proposals with the most disapproval, according to a poll by independent think tank Espacio Público-IPSOS. In this way, the Rechazo sector managed to consolidate support around traditional Chilean identities that felt threatened by the notion of plurinationality. This was reinforced by some Convention members’ actions and performances, including disparaging actions and comments concerning the national anthem, the flag, and other patriotic symbols. Although these positions were not expressed in the draft constitution, they served as munitions for the Rechazo campaign.

The Second Plebiscite

The alignment of Chile’s political forces for the September 4 exit plebiscite came as no surprise. All the parties from the Democracia Cristiana to the left sided with Apruebo, although some leaders rebelled against the official position. All right-wing parties supported Rechazo. Within both camps, however, there was variation.

Early on, differences emerged between those who supported rejecting the draft to maintain the existing constitution with a few minor reforms and those who preferred an entirely new process to create another draft. As the campaign advanced, the latter became the leading voices of the Rechazo campaign.

On the Apruebo side, there was disagreement about what would have occurred during the implementation of the draft constitution, if the country voted to approve it. However, as Apruebo trailed Rechazo in the polls, the official parties that supported Apruebo became open to the idea of making changes to the draft. They accepted that revisions were necessary to mitigate public concerns, like the resentment about implementing plurinationality. This view was reinforced by a series of surveys showing that Apruebo remained far behind Rechazo and that the majority of Apruebo supporters believed the draft constitution would require modifications after being approved. Well into the campaign and with different levels of enthusiasm, these parties signed an agreement to carry out these proposals after the plebiscite.

Ultimately, the plebiscite that had only two options on the ballot ended up being about four choices: approve, approve to reform, reject, and reject to restart. In one of the final polls carried out by Cadem, 17 percent of those surveyed were in favor of simply rejecting, 35 percent of rejecting to restart, 32 percent of approving to reform, and only 12 percent of approving and implementing the original draft constitution.

The “no” vote in the September 4 plebiscite was very different from the initial plebiscite on whether to rewrite the constitution. This wasn’t only because the rejection was larger, but also because it permeated more sectors of society than just the “three comunas.” According to polls, Rechazo was leading without significant differences across socioeconomic levels, and the September 4 vote confirmed this trend. In the Santiago metropolitan region’s poor and working class comunas, Apruebo should have swept the vote but only managed victories by small margins.

There was a difference, however, in the ideological profile of voters, with Apruebo winning comfortably among those who identify with the left. Rechazo was for the most part those who identify with the right and center, and people who do not identify with either the left or right. There was also a significant difference in votes by age; Apruebo was victorious among youth between 18 and 30, while Rechazo won among all other age ranges. Thus, unlike in the initial plebiscite, the Rechazo campaign managed to create a more diverse social and political alliance than Apruebo.

Why Did Rechazo Win?

At this point there are two interpretations—which, incidentally, are not mutually exclusive—for the decrease in support for Apruebo and increase for Rechazo: the first emphasizes the “average voter,” which assumes an abrupt break from the ethos of the 2019 uprising; the other points to the reaction of traditional identities that united against the draft constitution and presumably recognizes that the uprising was clearly anti-elite but not necessarily “leftist.”

In the first interpretation, the initial plebiscite and the vote for Convention members were marked by the dispute between the people and the elite. This configuration of political power mostly erased the distinctions between the left and right and between the diverse interests and visions of the public. However, according to this interpretation, the dispute between “above” and “below” has ended, and, in its place, the classic conflicts between the left and right have returned. According to some polls, the Rechazo campaign was associated with combating drug trafficking and economic growth, while Apruebo was correlated with the redistribution of wealth through social rights, positions typically associated with the right and left, respectively.

What this perspective implies is that the current constitution is to the right of the average voter, while the failed draft constitution is to the left. This would explain the success of the options “reject to restart” and “approve to reform.” Ultimately, according to this interpretation, the plebiscite was won in the center of the political spectrum. This theory also supposes that the main shortcoming of the constitutional process was the lack of agreement with the Convention’s right on key topics, like the political system. In keeping with this idea, 77 percent of people surveyed said they preferred that Convention members reach agreements, even if it meant yielding in certain areas. Meanwhile, 61 percent thought that Convention members had not budged in their positions.

The second interpretation assumes that the ethos of conflict between “above” and “below” persisted, but that, over the course of the process, the anti-elite position shifted to the right. The events that occurred during the past two years allowed the right to contest the left’s long standing monopoly on popular defiance, and, even more significantly, indignation. Instead of strengthening the moderate center, what occurred was a reinforcement and politicization of traditional social identities.

From this perspective, the success of the non-polar positions—“approve to reform” and “reject to restart”—indicates that many citizens have complex social identities that don’t clearly map onto the current political conflict. As Government and Politics professor Lilliana Mason explains, when the supporters of a political stance are clearly socially homogenous, affective polarization tends to result. On the other hand, the existence of complex identities fosters depolarization. In other words, it is possible that, for many people, their partisan identities of class, religion, age, ethnicity, or place of residence were tugged in opposite directions for this plebiscite, pushing people towards center positions in the debate.

According to this view, the main failure of the constitutional process was the inability to incorporate these traditional identities into the symbolic process of creating a new magna carta. In particular, they needed to find a way to present plurinationalism within the framework of inclusive patriotic sentiment. This is certainly conspicuous in the most intemperate declarations by Convention members and in performances that, when executed from a place of power instead of opposition, seemed derogatory towards people with traditional national identities. There are also concrete constitutional norms that could have been written to more clearly explain equality within the context of diversity. For example, the limits of the justice system and autonomy for Indigenous peoples could have been more explicit.

The Third is Defeated

There appears to be a relatively broad consensus that a constitutional stalemate is not a viable option. Moreover, there seems to be some agreement that a new constitutional process must include citizen participation. This will likely also involve the creation of a new Convention and another plebiscite to ratify a new draft constitution. It is thus highly probable that Chile will face a third constitutional plebiscite in a few months.

The exact form that this process will take remains to be seen, and, beyond the interests at play, it will depend on which of the described analyses ultimately rings true. If the Rechazo win is seen as a product of the demand for greater center-moderate presence and more dialogue between the left and right, then the tension will be around the options for independent candidates. One aspect that defies this assessment is the anti-party sentiment that has existed for the last two years. According to a Criteria survey, 82 percent of those polled prefer that members of a new Convention not belong to any party, with no significant statistical difference compared to October 2020. However, the same poll shows that the preference for “experts” has grown from 63 percent to 80 percent. In contrast, support for “ordinary people'' dropped from 37 percent to 20 percent. This complicates the interpretation of conflict between “above” and “below” and could reinforce the idea of seeking a Convention more inclined to agreement.

If, on the other hand, the analysis emphasizes the identity conflict, it will call into question how many seats should be reserved for Indigenous groups in the process. It is also likely that a new process will be marked by greater care for patriotic symbols. A clear shift in this regard can be seen near the end of the original constitutional process: it was not for nothing that the Chilean flag was selected as the symbol of the draft constitution.

The challenge facing Chilean politics is to reach a new agreement that will finally allow for the creation of a new draft constitution with broad and cross-cutting popular support. In doing so, it will be important to remember how quickly the hope and support for a process can plummet if expectations are betrayed.

Noam Titelman is an economist and doctoral candidate at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He was president of the Students’ Federation at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) and currently is a member of the Revolución Democrática.