Less than three months ago, Bolivian president Evo Morales signed a law cancelling the government’s proposed highway through the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), following a 360-mile, 65-day cross-country protest march by lowland indigenous groups. Now, the controversial road project appears to be on the verge of resurrection.

A pro-highway counter-march led by CONISUR, a regional organization representing 21 indigenous communities in the southern portion of the TIPNIS, left the park on December 20 and is expected to arrive in La Paz next week. These groups are demanding that the government annul the new law protecting the TIPNIS as an “untouchable” reserve, revive the highway project, and provide social and economic development programs for the southern zone.

The reasons underlying the CONISUR communities’ support for the road are both political and economic. CONISUR is a dissident faction that split off from the TIPNIS Subcentral (legal owner of the TIPNIS indigenous territory) in the 1990s. According to the website of its parent organization, CONISUR was “basically created and supported by the Cochabamba prefecture [departmental government].”

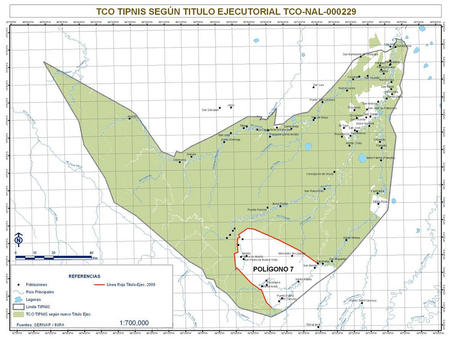

Within the TIPNIS indigenous territory, CONISUR represents only 12 of 63 communities. The other nine CONISUR communities are located inside the “red line,” a section of the park which is excluded from the collective land title (see map, Polygon 7). Since the 1970s, this area has been colonized by migrant settlers, primarily coca farmers, who own their land individually. An estimated 20,000 settler-farmers inside the red line vastly outnumber the indigenous population (approximately 12,500 residents in the park as a whole).

Unlike indigenous groups elsewhere in the TIPNIS who still rely on hunting, fishing, and subsistence agriculture, the CONISUR communities have become dependent on the southern zone’s coca-dominated cash economy, both legal (inside the red line) and illegal (outside). According to a recent Fundación Tierra report, indigenous farmers mostly provide seasonal low-wage labor for the coca harvests, though some have small individual plots and a few are even affiliated with the powerful coca growers’ union federation of the tropics (still headed by Morales). The president of CONISUR recently acknowledged that five to seven of its communities are involved in coca cultivation.

Despite their exploited status, these groups perceive a shared economic interest with the region’s farmers upon whom they are dependent, who support the road to market their products—especially citrus fruits and other coca substitute crops that are more difficult to transport. They also see educational and economic benefits from the expansion of schools and services promised by the government in conjunction with the road. This includes the annual “Juancito Pinto” school attendance bonus paid to students’ families, which the government has recently been promoting in the CONISUR communities.

Since the start of the TIPNIS conflict, Movement for Socialism (MAS) government officials have made frequent visits to the CONISUR communities to rally support for the highway from an indigenous base. According to Dario Kenner's Bolivia Diary, 15 of the 21 CONISUR communities are participating in the roughly 1,000-person counter-march. While Morales has officially criticized the mobilization for targeting the government (instead of the TIPNIS Subcentral leadership), he continues to be outspoken in stressing the need for the highway and encouraging pro-road sectors (including cocaleros, campesinos, and colonists) to make their voices heard.

Since the start of the TIPNIS conflict, Movement for Socialism (MAS) government officials have made frequent visits to the CONISUR communities to rally support for the highway from an indigenous base. According to Dario Kenner's Bolivia Diary, 15 of the 21 CONISUR communities are participating in the roughly 1,000-person counter-march. While Morales has officially criticized the mobilization for targeting the government (instead of the TIPNIS Subcentral leadership), he continues to be outspoken in stressing the need for the highway and encouraging pro-road sectors (including cocaleros, campesinos, and colonists) to make their voices heard.

The MAS government has played a prominent role in other recent events which have contributed to the seeming groundswell of pro-road sentiment. A December 7 rally organized by the Governor of Cochabamba mobilized thousands of highway supporters, with work schedules officially adjusted for both public and private sector employees to encourage attendance. On December 16, the Governor of Beni, a vocal critic of the TIPNIS road, was suspended by the MAS-dominated Departmental Assembly following an indictment for financial irregularities. His MAS-allied successor has now joined with the Governor of Cochabamba to spearhead an inter-departmental campaign to revive the road.

A government-sponsored “social summit” in January, billed as a consultation with civil society groups to determine the direction of Bolivia’s “process of change,” has called for a reconsideration of the TIPNIS highway ban. The summit was boycotted by CONAMAQ and CIDOB, the highland and lowland indigenous federations that oppose the road and participated in the earlier mobilization.

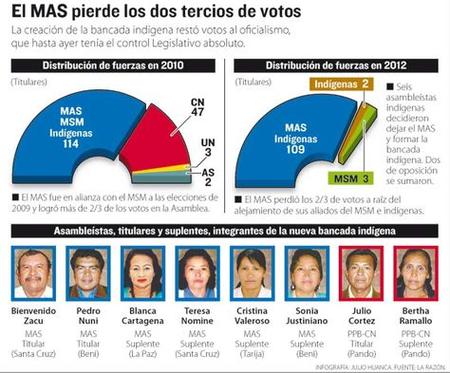

On January 13, the MAS-controlled Plurinational Assembly agreed to consider the counter-march’s demands, paving the way for possible changes to the law that protects the TIPNIS. While some prominent MAS legislators want to petition the Constitutional Tribunal to declare the law unconstitutional, others are seeking to modify or annul the law, which will require a 2/3 vote.

This strategy may be thwarted by the formation of a new “indigenous bloc” within the Assembly whose members have pledged to protect indigenous rights, and specifically to defend the TIPNIS law, despite party dictates. The bloc includes two voting MAS deputies (as well as four alternates). Combined with three deputies formerly allied with MAS who have defected from the party orbit, this could be sufficient to deprive the MAS of its 2/3 majority—unless alliances can be forged with individual deputies across party lines, which frequently occurs.

Another legislative strategy gaining traction is a revival of the much-debated proposal for a consulta with indigenous TIPNIS groups, to determine the extent of support for the road. This could potentially be carried out under a parallel law without modifying the existing one, although it’s unclear how any result calling for construction of the road could be implemented. The TIPNIS Subcentral has vigorously denounced this plan as an effort to sabotage the current law, and a violation of the government’s legal obligation to seek the “free, prior, and informed consent” of indigenous groups before signing agreements such a construction contract and funding commitment (which are still in effect for the TIPNIS road).

If a consulta is pursued, the issue of which groups can or should be consulted is bound to be controversial and divisive. As some analysts have noted, under the existing legal framework only those communities inside the TIPNIS indigenous territory have a constitutional right to participate in any official consultation process, and not the indigenous CONISUR communities inside the “red line” who are excluded from the collective land title. However, in the past the government has maintained that the Constitution’s prior consultation requirement does not technically apply to road construction projects, allowing leeway for improvised procedures.

CIDOB and the TIPNIS Subcentral have pledged to defend the indigenous territory with vigils, road blockades, and a human cordon if the road project is resurrected. They are considering sponsoring yet another march in conjunction with allied urban sectors, in broad defense of indigenous, environmental, and human rights protected by Bolivia’s Constitution.

While the conflicts among and between indigenous communities and the various social sectors over the TIPNIS road are authentic, stemming from their divergent economic needs and interests as currently perceived, it’s unclear what the MAS government hopes to gain by continuing to foment these divisions instead of seeking to resolve them (for example, by considering alternative routes). Perhaps it’s a strategy to divert expectant constituencies from pressing their competing claims against the government—by focusing them on their conflicts with each other instead. But further weakening the historic alliance of indigenous, peasant, worker, and urban sectors that brought Morales to power can only serve, in the long run, to undermine progressive change in Bolivia.

For more coverage, see Dario Kenner’s Bolivia Diary and Carwil Without Borders. Read more on the TIPNIS conflict on Emily Achtenberg's blog, Rebel Currents. See also, the January/February 2011 NACLA Report, "Golpistas! Coups and Democracy in the 21st Century;" the September/October 2010 NACLA Report, "After Recognition: Indigenous Peoples Confront Capitalism;" or the September/October 2009 NACLA Report, "Political Environments: Development, Dissent, and the New Extraction." Or subscribe to NACLA.