Leer este artículo en español.

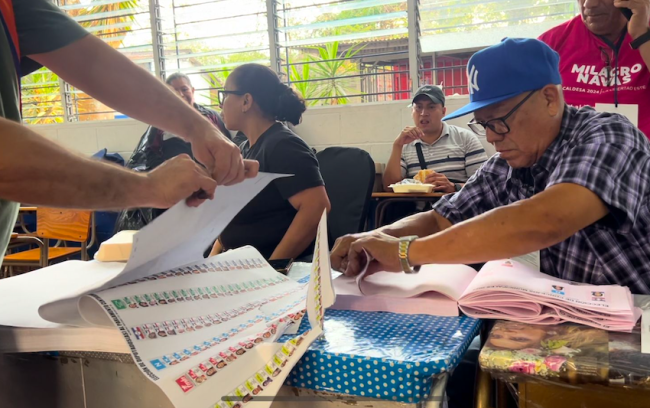

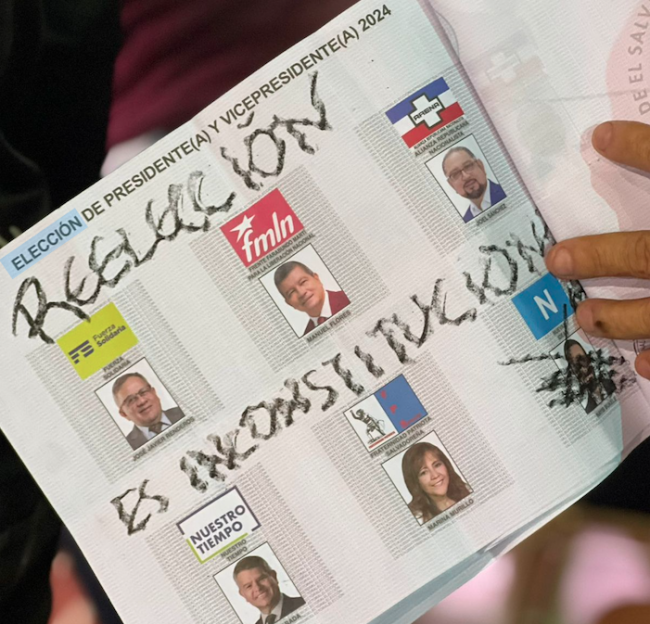

Nayib Bukele has changed the map of political pluralism in El Salvador. On February 4, in elections full of irregularities, the president was unconstitutionally reelected and managed to consolidate his Nuevas Ideas party as a hegemonic political force by winning 54 of 60 seats in the Legislative Assembly. Despite complaints of fraud by the opposition, which recorded at least 60 anomalies during the final count of the votes for president and legislators, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) proclaimed Bukele the winner, enabling him to govern the country for another five years.

On February 4 and March 3, El Salvador held two elections that have drastically changed the political and electoral system in place since the end of the country’s 1980-1992 civil war. Bukele’s allies had already achieved a majority in the congress in the 2021 elections, which gave the president the power to quickly dismantle democratic institutions. Ahead of the latest elections, however, it was a change in electoral rules that allowed Nuevas Ideas to win more power than it otherwise would have achieved. This change had to do with the reduction of the number of legislative seats and municipalities.

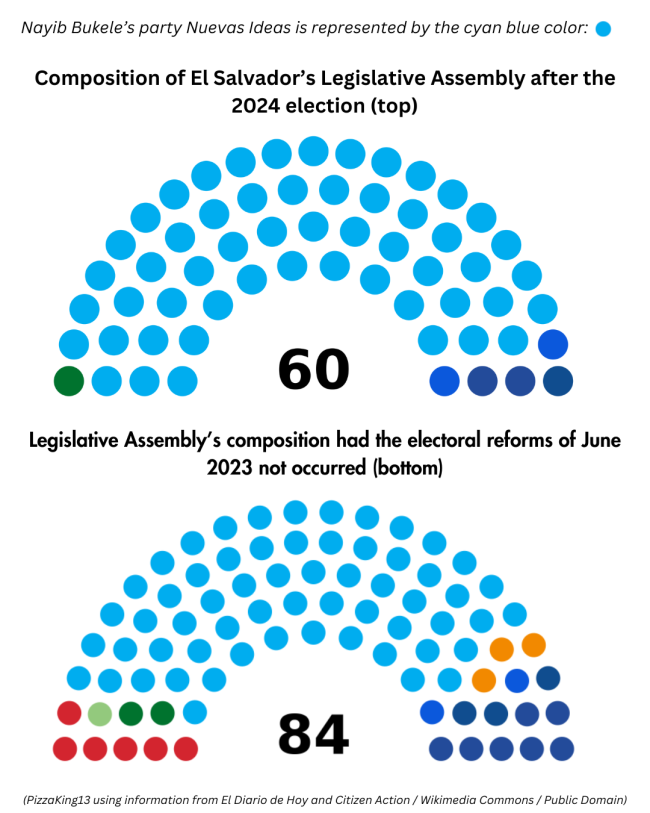

With the reforms, approved by the Bukele-dominated congress in June 2023, the number of municipalities was cut from 262 to 44 and the number of legislative representatives was reduced from 84 to 60. The 262 municipalities became districts that were distributed—without a technical study—among the 44 newly defined municipalities. For some experts, these reforms are unconstitutional, but the ruling party claims that the changes allow for more pluralism. “We comply with what the constitution says and we do reform to the extent that the vote is free, direct, and equal,” Nuevas Ideas lawmaker Dania González said in an interview two days before the municipal elections.

However, the election results demonstrate the opposite: the six remaining seats not won by Nuevas Ideas were divided between ARENA, which governed El Salvador for 20 years from 1989 to 2009, which obtained two seats; the National Coalition Party (PCN), also with two seats; the Vamos party with one; and the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), also with one. This is the first time since the signing of the 1992 peace accords that the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), the left-wing party that governed the country for 10 years from 2009 to 2019, has been left without representation in the legislature and without a single mayor in office.

“After these results, there will have to be a new beginning, a new total reorganization of our political project,” declared FMLN general secretary Óscar Ortiz the day after the March 3 elections. The FMLN debacle has opened a new debate about whether this party should continue or if a new left-wing political force should be born.

In municipal terms, the outlook for ARENA in the March 3 elections was also discouraging, with the party winning only one mayor’s office in La Libertad Este, a municipality that includes the districts of Antiguo Cuscatlán, Huizúcar, Zaragoza, San José Villanueva, and Nuevo Cuscatlán, located southeast of the capital. Longtime mayor of Antiguo Cuscatlán, Milagro Navas, won by almost 10,000 votes over her Nuevas Ideas opponent Michelle Sol, minister of housing in Bukele’s government and among the president’s closest circle. “I am David against a Goliath,” Navas said on the night of March 3 during a party in the central park of the municipality that she has governed for 36 years, celebrating having secured a 12th term.

“A Drastic Reduction in Political Pluralism”

According to experts, if not for the reforms, the election results would have been different, especially in terms of the number of lawmakers that each party obtained. Malcolm Cartagena, a expert in electoral law, calculates that with the previous system, Nuevas Ideas, having won 70.56 percent of the votes, would have secured 44 of the 60 seats in the legislature rather than 54—that is, 73.3 percent of the seats as opposed to 90 percent.

The difference is due to the fact that these elections applied the D'Hondt method, which proportionally distributes seats, rather than the Hare method of quotas, which was applied in the past to count legislative votes. The D'Hondt formula tends to favor large parties, and in El Salvador, that is what happened.

The impact of this change in the electoral formula was exposed in a third preliminary report on the elections from the Organization of American States Observation Mission, published on March 5. In the report, the observation mission stresses that these reforms, approved “three months before the elections were called (in October),” without debate with the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, “implied a drastic reduction of political pluralism in the highest body of decision-making and political control of El Salvador.”

For Cartagena, the report only “confirms what many of us have said since [the reform’s] approval: this reform implies a drastic reduction in political pluralism.” Laywer and electoral law expert Ruth López adds that it is precisely because the reforms affect pluralism and representation that they are unconstitutional. According to the constitution: “The political system is pluralist and is expressed through political parties.”

For López, there is no doubt that the reform fulfilled its mission. “The reform only had one objective: to achieve through electoral engineering what could not be achieved with the votes of the citizens, maintaining municipal control,” she says.

Of the 44 newly definied municipalities, Nuevas Ideas will govern 24. The vast majority of the rest will be in the hands of parties such as the PCN, PDC, and GANA, which Bukele considers his allies. In fact, on the night of the March 3 elections, Bukele claimed to have won “43 of 44 mayorships.”

“IN EL SALVADOR WE LIVE IN A DEMOCRACY AND THE PEOPLE'S DECISION IS RESPECTED,” he wrote on his X account. “However, the people are wise and the new mayors belong to parties that are indisputable allies of our project; parties that have always been there to support all the changes that our country has needed, since before winning the presidency in 2019,” he continued.

Bukele's words came after the results showed that his party had not managed to win a majority of municipalities, nor win key mayors’ offices where Nuevas Ideas had bet all its political machinery to seize power. This was the case in La Libertad Este, where ARENA won, and La Libertad Costa, which includes the Bukele government’s flagship Surf City project, where there are strong economic interests at play and GANA won.

For López, a point that cannot be overlooked is the fact that there were municipalities where Nuevas Ideas won the mayor’s office without having won the popular vote in any single district, as happened in La Libertad Norte, made up of the districts of Quezaltepeque, San Matías, and San Pablo Tacachico. The ruling party didn’t win in any of these three districts, but once the votes were added up, it achieved a threshold to govern. This reality is another example of the distortion caused by the reduction in the number of municipalities. “It’s the organization of the constituencies and the new districts that produces [a situation in which] municipalities, where a political party that did not win any district, has obtained the mayorship,” López warned.

When a Party “Knows it Won’t Lose”

Bukele's unconstitutional reelection comes in the midst of an ongoing state of exception, in place for almost two years. While the measure has detained more than 73,000 people in the name of “fighting gangs,” human rights organizations have denounced hundreds of arbitrary arrests as well as deaths inside prisons. The Salvadoran human rights organization Cristosal, which has documented human rights violations under the state of exception, has even warned that El Salvador may have committed crimes against humanity. The Salvadoran government has admitted to a “margin of error” within the total number of arrests, resulting in around 7,000 people being released, according to the Ministry of Justice. For human rights organizations, the fact that the elections were held under a state of exception could have been a determining factor when voters cast their ballots.

In the February 4 elections, Bukele was elected with the support of 43.48 percent of the total number of people eligible to vote. That day, according to data from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, 52.7 percent of the population exercised their right to vote. If that election already raised concerns about low voter turnout, on March 3, the levels were even more worrying: only 30.1 percent of the population cast their ballots, the lowest participation recorded by the TSE since the return to democracy. The abstentionism could be attributed to distrust in the results of the February 4 elections, in which the opposition said it had documented at least 60 anomalies that called into question the final count.

“There is still a long way to go for El Salvador to have efficient, better organized, more transparent, and, above all, more equitable electoral processes,” said the head of the OAS election observation mission, Isabel de Saint Malo, in a video published with its preliminary report.

Álvaro Artiga, a political scientist at San Salvador’s Central American University, is clear that Nuevas Ideas has managed to establish itself in El Salvador as a hegemonic party—a party that could simply use satellite parties to legitimize electoral processes or obtain elected positions. As an example, he points to Nicaragua, where elections have allowed the continuity of the hegemonic party without power being in dispute. With hegemony, such a party “knows it’s not going to lose, and if it loses, it can distort the results,” Artiga warns. “And it will be in charge of preventing the opposition’s organization.”

Translated from Spanish by NACLA.

Julia Gavarrete is a Salvadoran journalist focused on covering politics and human rights violations. In 2023 she received the Ortega y Gasset Award in the Best Story category. Until 2024, she was part of the El Faro newsroom.