In the leadup to the 50th anniversary of the bloody September 11, 1973 civil-military coup, the Chilean House of Representatives voted on August 23 to condemn the sexual political violence that took place during the Pinochet dictatorship. Among the 15 lawmakers who voted against the motion—in addition to 35 abstentions—was Gloria Naveillán, a representative of the far-right Republican Party for the southern Araucanía district. Justifying her negative vote, Naveillán claimed that allegations of sexual political violence during the dictatorship “are not proven.” She argued that discussions of sexual violence should also include “the women who were raped during the Popular Unity government” of ousted President Salvador Allende. When asked whether sexual political violence was systemic during the dictatorship, she added: “I don’t know if [cases] were systemic, I don’t think they were. I think that that is part of an urban legend.”

Compared to previous September 11 anniversaries—particularly the 30th and 40th commemorations—many academics and activists have noted that this year’s anniversary is marked by “backtracking.” Negacionismo (denialism) regarding the coup and the dictatorship are now much more public and stronger than before. Without a doubt, this has to do with the resurgence of right-wing, Pinochetista politicians and parties, especially those associated with Naveillán’s Republican Party. This is the party that catapulted José Antonio Kast to a first-round win in the 2021 presidential election. Although Kast was convincingly routed in the runoff by the young, left-wing current president, Gabriel Boric, the far-right played a key role in the “Rechazo” vote that defeated the progressive draft constitution in the September 2022 plebiscite. The party then became the largest bloc in the Constitutional Council now tasked with drafting a new proposed constitution.

Naveillan, for her part, became politically known by representing the interests of ultra-conservative Pinochetista agriculturalists from Arauco and Malleco who associate with the violent, far-right group Association for Peace and Reconciliation in the Araucanía (APRA). She is the daughter of Juan Jose Naveillán Fernández, an early “Chicago Boy” who was an ardent supporter of Pinochet’s neoliberal revolution, both as a businessman and an advisor in the dictatorship’s Economic Ministry. Gloria was born in 1960 in Chicago, where her father earned an MBA, and her family ties run deep both in the dictatorship and the Araucanía region.

Of course, as many with even a passing knowledge of Chilean history and human rights violations are aware, Naveillán’s statements about sexual violence during the dictatorship are patently false. Sexual political violence was deeply systemic and has been proven so through numerous trials, truth commissions, academic studies, and activist organizing. The final report of the 2003-2004 National Commission on Political Prison and Torture, known as Valech I, officially recognized 3,399 women victims, most of them survivors of sexual political violence. Another report, Valech II, released after a reopening of the truth commission from 2010 to 2011, collected testimonies from an additional 1,580 women.

Recent trials, such as those spearheaded by special human rights judge Mario Carroza, have also made important inroads in judicially recognizing sexual political violence. On August 22, the Supreme Court upheld guilty verdicts for three former DINA secret police agents— Manuel Rivas Díaz, Hugo Hernández Valle, and Raúl Eduardo Iturriaga Neumann—who were accused of the kidnapping and torture with sexual violence of six women: Cristina Verónica Godoy Hinojosa, Laura Ramsay Acosta, Beatriz Constanza Bataszew Contreras, Sara Gabriela de Witt Jorquera, Carmen Alejandra Holzapfel Picarte, and Clivia Marfa Sotomayor Torres. The abuses took place between 1974 and 1975 in the former torture center known as “Venda Sexy” or “La Discotheque,” located on 3037 Iran Street in Santiago’s Macul neighborhood. The building, known as a site of numerous cases of sexual political violence, was recently expropriated, with compensation, by the Boric government—an important step in transforming it into an official memory site.

As a rebuke of Naveillán’s repugnant statements, the Feminist Historians Network (RHF), where I am one of the coordinators, published a declaration on sexual political violence and denialism. “Sexual political violence was used against a wide array of women, including women who were party members and sympathizers, as well as women family members of party members, in torture centers and political prisons,” RHF wrote. “However, beyond these specific sites, there was also sexual political violence that was carried out against shantytown women, peasant women, feminists, lesbians, and trans and travesti women, among others, in contexts of political raids, protests, and other scenarios wherein state agents carried out state terrorism.”

Memorializing the Women’s Locker Room

As part of the 50th anniversary commemorations, on September 5, I was invited to attend a talk on sexual political violence and justice by Lidia Casas, a feminist lawyer and head of the Human Rights Center at the Universidad Diego Portales. The event was held at the National Stadium in Santiago—the largest political prison and torture center used by the dictatorship immediately after the September 11, 1973 coup—and more specifically in the Sitio de Memoria Camarín de Mujeres, a memory site to commemorate the “Women’s Locker Room,” where it is estimated that approximately 1,200 women were held prisoner.

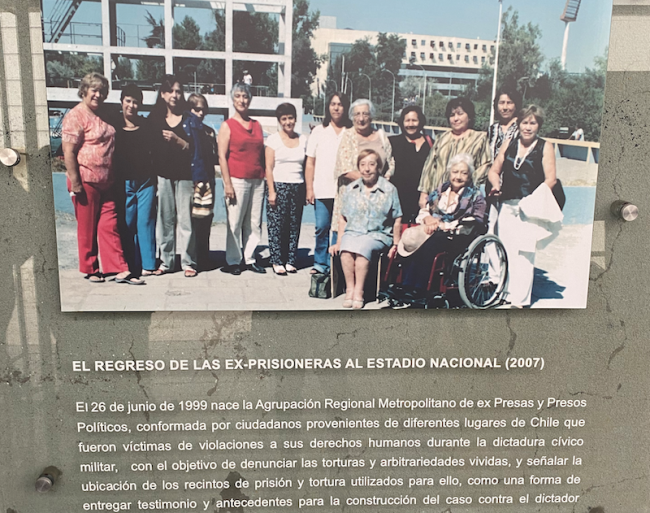

Before Casas’s talk about the systemic and widespread use of sexual political violence during the Chilean and other Latin American dictatorships, we were invited to visit the memory site and observe the panels and artwork that had been installed. Although I had been to the National Stadium many times for previous September 11 commemorations, I had never been inside this particular part—a relatively new memory site. The National Stadium and its grounds are currently under renovation and expansion in preparation for the Pan-American and Parapan-American Games that will be held in Santiago starting on October 20, 2023. This backdrop lends a particularly strong mix of the mundane, the everyday, and the exceptional to the horror of this specific memory site. Ever since its use as a torture center and political prison in 1973, the National Stadium has been under constant pressure to continue serving as a major venue for music and sports events.

The memory site itself is a rectangular cement block, divided into three main areas. The first area when entering is primarily surrounded by glass walls, with chairs for events and a rotating gallery of politically themed artwork. This space, where the talk took place, also includes plaques and banners that honor the tireless work of the Ex-Women Prisoners of the National Stadium to have the Women’s Locker Room identified as a memory site. The second area is the locker room itself, which actually bears the title “Camarín de Caballeros” or Men’s Locker Room carved in cement above. This area is considerably darker than the first, due to a lack of natural light, and feels more chilled, due to the dampness, cement, and absence of direct sunlight. As I visited this area around the same time of year as the civil-military coup, it was not hard to imagine how this area could have been extremely cold and inhospitable for the women prisoners, particularly at night and if it was raining, which it tends to do at this time of year.

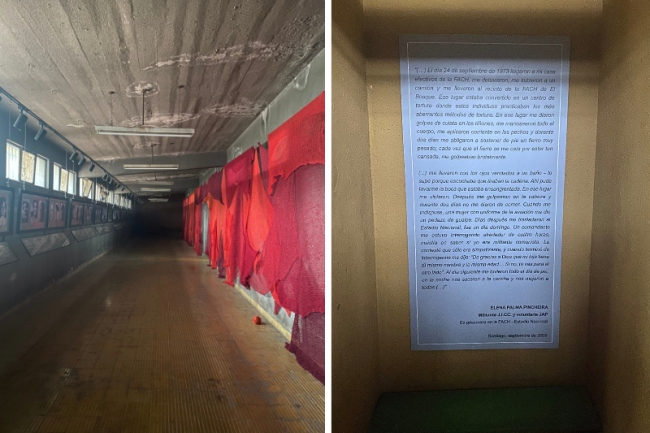

The locker room consists primarily of a series of small rectangular cement booths that were, at one time, used as changing rooms for the stadium’s pool. The left-hand side (west wall) displays 405 copper plaques, installed in 2018, with the names of women political prisoners. To the right, and extending to the east wall, are two sets of changing rooms, separated by a hall area. On the south side of the changing rooms, long white canvases bear typed poetry by women political prisoners, identified by name and where they were held prisoner. On the north side, canvases display typed testimonials of women political prisoners who were held at the National Stadium, identifying them by name, political affiliation (if any), and the torture centers and political prisons they passed through. Both in the poetry and the testimonials, the horror of state terrorism and sexual political violence is present. However, so too is the solidarity and resistance of the women political prisoners, an aspect I have explored as a feminist historian in various publications.

The last and final area of the memory space is a long rectangular cement hall with small rectangular windows on the upper side of the north wall. Underneath these windows are a series of black and white photos of women political prisoners. The photos are accompanied by the woman’s name, age, and a short personal description. In many cases, the women are professionals, members of political parties, and over the age of 40, which goes against many prevailing ideas about political prisoners as being primarily young women militants and sympathizers. Undoubtedly, this memory site specifically seeks to showcase the social, political, professional, and age diversity of the large number of women who were held at the National Stadium immediately following the 1973 coup.

On the other side of this room, a large, red, crocheted fabric installation hangs down the length of the south wall. This installation is part of the memory project, Sangre de mi sangre (Blood of My Blood), created by the Colectiva Hilos Chile, an interdisciplinary art collective launched in 2022 following the spirit of a group originally founded in Mexico in 2018. For the 50th anniversary of the coup, this collective has been carrying out sentadas textiles (textile sit-ins), where people are invited to collectively weave large red fabric pieces that are then installed in memory sites such as Londres 38, Venda Sexy, Villa Grimaldi, and the Women’s Locker Room.

Although Gloria Naveillán and others on the far right will continue to deny and flagrantly lie about sexual political violence in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship, the testimonies, artwork, photos, installations, guided tours, and academic and activist work at the Women’s Locker Room Memory Site remind us that memory and history continue to play an important role in the fight against denial and “fake news.” Truth, justice, and integral reparation for the women who passed through this political prison and torture center – and many others like it throughout Chile – are extremely important not only for combatting lies and misinformation, but also for healing individual and collective traumas. Sexual political violence must be widely and publicly recognized for what it was in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship: not an “urban legend,” but a horrific urban, and rural, reality.

Hillary Hiner is Associate Professor in the Escuela de Historia at the Universidad Diego Portales in Santiago, Chile, and the coordinator, in the Central Zone, of the Feminist Historians Network.