Almost four years after the administration of former Colombian president Iván Duque suspended peace talks with the leftist National Liberation Army (ELN), the administration of President Gustavo Petro formally resumed talks with the guerilla group last week in Caracas. As Colombia and Latin America’s oldest and now most powerful armed group, the success of Petro’s commitment to “total peace” rests in no small part on the commitment of the Venezuelan government to also engaging in negotiations with the ELN.

Several signs bode well on the part of both the new administration and the ELN. Petro was himself a member of the leftist M19 guerrilla group and has put together a respected and ideologically heterodox peace delegation. Among the government’s negotiators are former guerrillas, civil society leaders, active military personnel and conservative Colombian Federation of Ranchers (FEDEGAN) president José Félix Lafaurie.

Colombians and observers alike are hopeful that the ELN may follow in the footsteps of the infamous Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and demobilize as the latter guerrillas did in 2017. While smaller in overall manpower than the former FARC, the ELN is a markedly distinct organization both in its territorial scope and its organizational hierarchy.

The ELN is unique in that it is perhaps the first and only Marxist guerrilla group with a significant foothold outside its country of origin, in neighboring Venezuela. Today the group is effectively a Colombo-Venezuelan guerrilla army, meaning that the role of both Colombian and Venezuelan authorities will be integral to successful peace talks.

Borderlands of Conflict

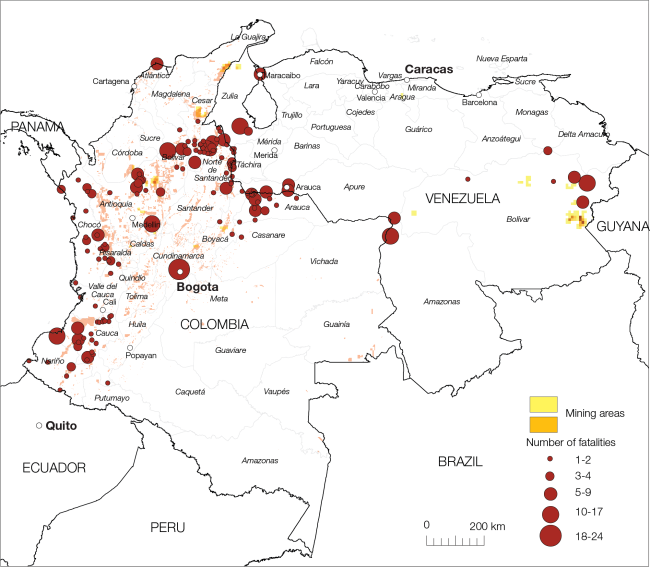

In a recent paper published in the Journal of Latin American Geography, we mapped over 2,100 violent incidents perpetrated by the ELN in both Colombia and Venezuela. Our findings show that fatalities and events attributed to the ELN in both countries have risen exponentially since 2017, with the demobilization of the FARC and Venezuela’s ongoing crisis being key to expansion. Of the 390 fatalities attributed to the ELN between 2017 and 2021, around a quarter took place in Venezuela.

Additionally, approximately one-third of the group’s 3000-4000 fighters are thought to be of Venezuelan origin, with fighters active in at least half of Venezuela’s 23 states. The group has also repeatedly expressed a commitment to the defense of the Bolivarian Revolution from enemies both foreign and domestic. While the advent of Colombia’s first leftist government represents a historic shift, the ELN will likely continue to have divergent ideological and transactional aims in Colombia and Venezuela.

The ELN’s activities in Venezuela have changed considerably since the late 1990s. Like neighboring Ecuador, attacks within Venezuela were largely rare and isolated incidents. For most of its history, the group used Venezuela’s borderlands as a safe haven for planning attacks and evading Colombian authorities. However porous, borders in Latin America remain effective deterrents against strikes by security forces, particularly when relations between neighboring states are unfavorable.

Prior to 1999, Venezuela and Colombia shared intelligence and engaged in joint military operations along the Colombo-Venezuelan border. After Hugo Chávez came to power in 1999, this was no longer the case, except for a brief period between 2002 and 2004. Under successive left-wing governments in Venezuela and respective right-wing administrations in Colombia, relations between the two countries increasingly deteriorated. It’s well known that the Venezuelan military supplied Colombian guerrillas with weapons and munitions throughout the 2000s and 2010s. Similarly, Colombian security and intelligence services are thought to have aided or condoned efforts by the Venezuelan opposition to depose Nicolas Maduro during 2020’s Operation Gideón.

Insurgency as Organized Crime

The ELN is actively involved in illicit economies such as coca cultivation and extortion. In practice, crime has become as much a means as an end for many within the ELN’s fronts. ELN activities in Venezuela, for instance, are prevalent along the Orinoco Basin as well as along the Colombian border. In recent years, Venezuela’s Orinoco has been devastated by a violent gold rush regulated by the ELN and other armed actors.

Similarly in Colombia, ELN activities are prevalent, though not unique to, municipalities with high concentrations of coca crops. Peace between the Colombian government and the FARC was a boon for the group, as the guerrillas and other armed actors rushed to fill the void vacated by the FARC. For the ELN, this meant securing much of Venezuela’s borderlands, with the guerrillas now controlling at least a third of the Colombo-Venezuelan border.

Since 2014, the ELN also benefited from Venezuela’s ongoing humanitarian crisis. By 2019, the Maduro administration allegedly viewed the presence of Colombian guerrillas on Venezuelan soil as a useful bulwark against military intervention by Colombia and/or the United States. Three years later, Human Rights Watch reported that the Venezuelan military engaged in joint operations with ELN fighters against FARC dissidents in the war-torn state of Apure.

It’s a mistake, however, to presume that the guerrillas are pawns of the government in Caracas. The ELN has agency and its fighters have clashed just as often with Venezuelan forces as with other armed groups. Both ideological and transactional aims are key to the ELN’s goals. Broadly, the relationship between the Venezuelan state and groups like the ELN is both conflictive and sympathetic—not unlike that between right-wing paramilitaries and Colombian state.

Do They Want Peace? The Enigma of the ELN

The ELN is a far more decentralized guerrilla than the former FARC. On paper, the group is headed by a Central Command (Comando Central, COCE), with Eliécer Erlinto Chamorro, alias Antonio García, as top commander. The rest of the COCE is thought to be composed of five to seven commanders, some of which head regional blocs that oversee fronts of up to 100 combatants.

For this reason, there seems to be a disconnect between the COCE’s political leaders and the commanders of fronts on the ground. The COCE has shown that its authority remains influential given its continued ability to call and uphold national ceasefires. Nonetheless, bloc commanders—and especially Gustavo Aníbal Giraldo, alias Pablito, of the eastern Frente de Guerra Oriental (FGO)—are the primary drivers of military operations.

As of this writing, the bulk of the COCE (excluding Pablito) have not set foot in Colombia since the start of previous negotiations in 2017. Even after the suspension of talks in 2019, key leaders of the COCE such as Pablo Beltrán and alias Gabino stayed in Cuba as a show of good faith towards resuming negotiations.

During the same period, Pablito oversaw FGO operations on the ground in Arauca and Venezuela. The tragic car bombing of Bogotá’s Santander Police Academy in 2019 that killed 22 cadets was traced back to Pablito and the FGO, a clear and ultimately successful attempt at sabotaging negotiations.

Indeed, as negotiators met in Caracas last Monday, assailants lit eight freight trucks on fire near Cúcuta in Norte de Santander. The same day, high caliber explosives were defused at a rural children’s school in Arauca. The suspected perpetrators are the ELN’s Frente de Guerra Nororiental (FGN) in Norte de Santander and the FGO in Arauca.

It is telling and potentially damning that the ELN’s new peace delegation does not include the head of the guerrillas’ largest and most militarily powerful bloc, Pablito of the FGO. If last week’s attacks are any indication, it’s likely that we will see further—and more brutal—attempts by hardliners to derail peace talks.

At the same time, it’s promising that the delegation does not consist exclusively of political leaders such as Pablo Beltrán or Antonio Garcia. Figures such as Bernardo Tellez (FGN), Luz Amanda Pallares (FGN) and Juan de Dios Lizazaro (FGO) have storied backgrounds within their respective blocs and will be key to ensuring compliance from active fighters.

The Bolivarian Enigma

Like any authoritarian state, it can be difficult to interpret the inner machinations and motivations of the Venezuelan government. That said, it should be noted that under both Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela has consistently backed prior negotiations with both the FARC and ELN. There’s reason to believe, however, that the Maduro administration may not be fully committed to the ELN’s demobilization.

Even with the advent of Colombia’s first leftist administration, Colombia remains the United States’ closest strategic partner in the region. While he has called for a reevaluation of U.S. drug policy, Petro has nonetheless pursued good relations with North America. Petro has maintained joint military exercises with U.S. forces and authorized the extradition of drug traffickers wanted by Washington. He has also thus far neglected a campaign promise to renegotiate Colombia’s disastrous free trade agreement with the United States.

Despite restoring diplomatic and even military relations, Colombia and Venezuela are likely to continue viewing one another with suspicion. In recent years Petro has become increasingly critical of Venezuela’s extractivism and track record on human rights. Petro also decisively rebuked a request by President Maduro to extradite dissidents living in Colombia.

Consequently, the calculus in Caracas may be that it is better if the ELN persists as one of many non-state actors committed to the defense of the Bolivarian regime. On the other hand, officials in Venezuela may be weary of increasingly expansionist Colombian guerrillas. Both the ELN and ex-FARC have subjected the Venezuelan military to stunning and humiliating defeats. While Venezuelan security forces in Apure can currently count on support from the ELN’s FGO, they are likely aware that an ally today could morph into an enemy tomorrow.

It’s encouraging that Venezuela was reincorporated as a guarantor and site for the first leg of peace talks. Moreover, in his recent visit to Venezuela, President Petro showed some savvy in offering to moderate negotiations between the Venezuelan government and the opposition. As relations between Venezuela and the West continue to thaw, the Petro administration could be vital in securing further concessions for Venezuela, a fact the Maduro administration no doubt recognizes.

La Paz Total

For peace talks to succeed, negotiators, security forces, and the Petro administration will need to take great pains to assess the interests of the ELN’s regional blocs.

Petro’s proposal for paz total or “total peace,” a move to negotiate peace and terms of surrender with Colombia’s myriad armed groups, is highly ambitious. Petro has expressed a desire to dialogue with armed groups on a regional level. Thus, it may be more fruitful for negotiators to seek agreements with specific ELN blocs given the apparent divide between hardliners and leaders active in peace talks.

Already, over ten armed groups have joined a national ceasefire with the government. Under the legal framework drafted by the government, individual surrender has been expanded such that multiple individuals can negotiate collectively with authorities. The modified Ley de Orden Público (Law for Public Order) also stipulates that drug traffickers within armed groups will receive legal benefits for revealing financial ties with superiors and legal enterprises that benefit from the drug trade.

Alternatively, groups such as the ELN and ex-FARC factions like the one headed by Ivan Márquez can engage in formal peace talks with the government. The latter point has generated controversy given that Márquez was a signatory of the 2016 Peace Agreement. Petro maintains—with some credibility—that Márquez’s 2019 drug trafficking charges were a set up by the DEA and former Attorney General Néstor Humberto Martínez. Nonetheless, Marquez’s case showcases the extremely thin line that exists between “criminal” and “political” armed groups.

Armed groups may also take advantage of a national ceasefire with security forces to fortify themselves militarily and combat rivals. During negotiations with the FARC (2012-2016), armed actors such as the ELN and AGC rushed to occupy and compete for territories vacated by the FARC. While this led to increased and ongoing violence in specific municipalities, attacks by the FARC itself declined throughout the course of negotiations and led to a substantial reduction in homicides nationally.

The Petro administration seems to have also learned valuable lessons from the extremely contentious peace process with the FARC. By incorporating the opposition into negotiations, any future agreement stands to benefit from greater legitimacy—and fewer attempts at sabotage—from the Colombian Right. The incorporation of FEDEGAN president Lafaurie, with backing from former president Álvaro Uribe, is a stunning development from a sector that once shunned negotiations at all costs.

Admittedly however, Colombians should be skeptical that total peace is realistically attainable in the near term. For every promising development, there have been equally troubling and gruesome acts committed by violent groups. Buenaventura went more than a month without a single homicide after the city’s two largest gangs announced a ceasefire in preparation for talks with the government. Conversely, fighting between FARC dissidents last weekend in Putumayo led to more than 20 deaths and hundreds of internally displaced.

Characterizations of the Petro administration’s approach toward security as improvised ignore the reality that military deployments against armed groups often follow similarly muddled security strategies. Both repression and negotiation are key aspects of armed conflict. Similarly, both require reassessment in light of changing circumstances.

Peace with the ELN, let alone other armed groups such as the AGC and ex-FARC, will require immense tact from the Petro administration and substantial support from Caracas. As Latin America’s oldest guerrilla army, successful negotiations will go a long way towards paving a lasting peace in Colombia.

Juan David Rojas (MA, University of Florida) is an intelligence fellow at Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy.

Olivier J. Walther, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in Geography at the University of Florida.