This piece appeared in the Summer 2023 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Leia este artigo em português.

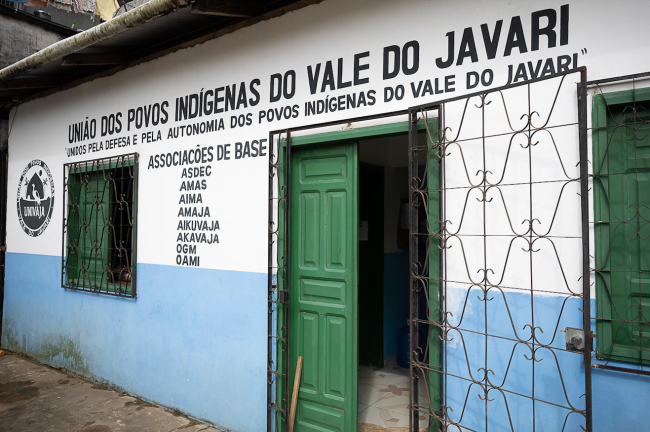

On November 17, 2022, two weeks after Brazil’s presidential elections, the Kanamari people of the Javari Valley released a public letter denouncing threats against one of their leaders. “This letter is a call for help,” the Javari Valley Kanamari Association (AKAVAJA) said in the statement. “We want help because we want to live.”

According to AKAVAJA, the incident took place inside the Javari Valley Indigenous territory on the morning of November 9. About 30 Indigenous community members were traveling on the Itaquaí River when they came across illegal fishing boats carrying turtles and fish. When approached, the fishermen initially offered turtles in exchange for silence. An Indigenous woman leader spoke up, seeking to mediate the conflict and questioning the fishermen’s incursion. The fishermen then threatened to kill her, pointing a gun at her chest. “The deaths in the Javari Valley won’t stop until the main leaders are murdered,” one of them reportedly said. The leader who confronted them would be on the list.

The threat continued: “I will take off my mask for you to see my face and warn you that it is due to situations like this that Bruno and Dom were killed by our team, and you will be next. The only reason I won’t kill you now is because we are in the presence of many children.” According to the statement, the fishermen followed the words with intimidation: they cut the engine wiring on one of the Kanamari boats and opened fire as they sped away, puncturing a gasoline drum on the roof of one of the boats.

Since the death of Marielle Franco in 2018, a new pattern of violence against human rights and environmental defenders has emerged in Brazil. In the Amazon, the news of Franco’s assassination came after brutal attacks, including a 2017 massacre at the hands of illegal miners of up to 10 members of an isolated Indigenous group in the Javari Valley. Invariably met with impunity, these attacks served as messages from landowners and miners of the lengths to which they would go to defend their interests.

The threats against the Kanamari leader in the Javari Valley in November offer a glimpse into the kinds of daily violence against Indigenous and traditional peoples that became widespread during the government of Jair Bolsonaro. While some incidents are reported, others happen in silence. What is clear is that the former president’s rhetoric and speeches contributed decisively to multiplying this violence by shaping public opinion and incentivizing hostile acts. Dissonant voices and actions were disallowed, as in the case of the reporting trip that journalist Dom Phillips and Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira were on when they were murdered in the Javari Valley in June 2022. Bolsonaro presented their trip as an “adventure”—that is, irresponsible.

Amid intensified violence under Bolsonaro, these and other recent cases draw attention to a pattern of violence against a backdrop of a crisis of hegemony. In times of rupture, a regime of terror invades communities, bringing consequences like internal divisions and co-option that weaken social movements.

Javari Valley Under Attack

The Javari River is a tributary of the Amazon, much like the nearby Juruá River, whose own tributaries—endless waterways branching off into paranás, igarapés, and furos—constitute an enormous capillarity network uniting the Brazilian states of Amazonas and Acre with the border areas of Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia. Dotted with officially recognized Indigenous territories and conservation areas—different kinds of land arrangements designed to preserve nature—this region has been frequented by armed groups since at least the 1990s, when the Sendero Luminoso provided security for the transport of cocaine base paste from Peru and Bolivia to laboratories in Colombia.

This movement of cocaine base paste over land and rivers, together with the trade of chemical inputs for making cocaine hydrochloride, made the fortunes of many traffickers and local elites in Rondônia, Acre, and Amazonas. In recent years, the situation has become more complex with the proliferation of laboratories and the expansion of Brazil’s largest criminal organization, the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), into drug routes in the region, according to researcher Ludmila Quirós.

Like other Amazonian territories, the Javari Valley has four important characteristics that contribute to the precarious situation environmental defenders face. First, the areas under threat are relatively isolated, which in most cases ensures that the perpetrators of illicit activities and/or threats escape with impunity. Second, the mosaic of protected Indigenous and conservation lands is in a strategic location in relation to transportation routes and the presence of commercially valuable natural resources like minerals, narcotics, and agricultural lands. Third, armed groups control access routes and passage through the territory. Finally, local powerholders are complicit, obstructing political processes, and pressuring city halls and lawmakers to submit to their interests.

When it comes to internal colonialism in the Amazon, self-styled “frontiersmen” (desbravadores) and “pioneers” are the ones responsible for advancing the economic frontier. As investors flock to the Amazon, “frontiersmen” are sometimes brought to the region as workers in logging, mining, and other enterprises. According to researchers Roberto Araújoa and Ima Célia Guimarães Vieirab, the frontiersmen’s defining characteristic, aside from loyal devotion to their bosses, is the pursuit of accumulation by any means necessary, which means they readily reject any and all attempts at regulation of their activities. As the frontier consolidates, “pioneers” become the political representatives of newly formed municipalities, exercising full control over elected powers and public security forces. When other actors—such as Indigenous peoples, social movements, and quilombo communities—compete with them for territory, these forces seek to relegate them to invisibility or insignificance.

Violence against these marginalized groups sometimes translates into the murder of human rights and environmental defenders, as documented by organizations like the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) in Brazil and Global Witness on a global scale. According to Global Witness, of the 342 killings of rights defenders in Brazil between 2012 and 2021, 85 percent took place in the Amazon, which “has become a backdrop to increasing violence and impunity.” The situation is emblematic of the country’s political crisis, including authoritarianism, attacks on democracy, and genocide of Indigenous peoples, such as the Yanomami case that came to light in early 2023.

Hatred of the Other

Beyond the material interests behind the felling of trees or grabbing of land, hate speech has been an increasingly important motivator of violence in recent years. Since 2013, a strong lobby has consolidated in Brazil’s National Congress under the banner BBB: beef, bullets, and bible. That is where Bolsonarismo arose. From his first day in office as president, Bolsonaro attacked the territorial rights of Indigenous and quilombo communities in favor of the invasion of land for speculation.

As a result, through his war against institutions, Indigenous territories, and other lands under public or collective control such as national parks, Bolsonaro opened new frontiers of expansion for private conquest. Deforestation, illegal gold mining, and other forms of violence, especially against Indigenous peoples, have systematically increased. Most significantly, these activities have consolidated in the so-called arc of deforestation in the Amazon.

This socially constructed hatred, spread at the economic frontiers of capitalist expansion, weaves together with local histories of racism, colonial domination, and the deconstruction of humanity. These are the characteristics of a deeply divided country, marked by clashes between enemies where differences must be resolved by eliminating the “other.”

Under the Bolsonaro government, the argument prevailed within government bodies that, given their supposed inability to produce goods—that is, to monetize the resources in the lands they inhabit—Indigenous and traditional peoples should share space with “entrepreneurs” engaged in mining, logging, ranching, large-scale soy farming, and other industries. At the beginning of 2020, while launching a vaguely defined Amazon Council headed by a retired general, Bolsonaro said: “More and more, the Indian is a human being just like us. So let’s make the Indians integrate into society.” Far from espousing ideals of equality, such statements reflected the idea that the constitutional rights of the Indigenous peoples, including the right to live on their ancestral lands, were no longer valid.

Read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time.

Translated from Portuguese by NACLA.

Felipe Milanez is a political ecologist and a professor at the Institute of Humanities, Arts and Sciences at the Federal University of Bahia.

Roberto Araújo Santos is an anthropologist and researcher at the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi.