This piece appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

While many had long proclaimed the death of the Pink Tide, the ouster of Bolivian President Evo Morales in 2019 was in some ways a nail in the coffin. The far-right government of Jeanine Áñez that followed unleashed the military on protesters, killing 30, persecuted those associated with the Morales government, threatened to privatize state industry, and disastrously mishandled the Covid-19 crisis. Yet just 12 months later, the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) returned, this time with Morales’s former finance minister, Luis Arce, at the helm. With him, the commitment to a progressive agenda, albeit financed through expanding extractivism, has returned.

By that time, Alberto Fernández had entered office in Argentina, ending a neoliberal reprise under Mauricio Macri. In Chile and Colombia, mass protests against inequality, neoliberalism, and repression at the hands of right-wing governments had begun to rattle the status quo. While six of the 11 countries that had elected left-leaning governments during the first 15 years of the 21st century remained in conservative hands, a new Left surge was building.

Since 2018, voters in eight countries have chosen the Left. For Colombia and Mexico, these elections marked their first national left government of the 21st century; for Honduras, a previous shift to the left was cut short. Yet these groundbreaking wins are muddied by the outsized influence of the United States in these countries, largely because of Washington’s preoccupation with its domestic issues of immigration and drugs. Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, on the other hand, are all on their second round of leftist leaders. Taken together, over 80 per cent of the region’s economic output is now in the hands of progressive governments.

Beyond labelling the current process underway in Latin America Pink Tide version 2.0, how are we to understand this new phase of left-identified governments? While they differ significantly from their predecessors, even more significantly, the world they face has changed.

Pink Tide version 1.0 was the most influential period Latin America’s Left has ever enjoyed, although, just as now, it was marked by considerable ideological and pragmatic differences between governments. Its defeat at the polls came for a series of reasons: voter fatigue after 10 years or more in power, inabilities to cultivate new leadership, severe economic contraction, mounting external debt obligations, and the rise of the far right. Pink Tide governments lost office through elections in Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Uruguay; a coup in Honduras; and “soft” coups in Brazil, Bolivia, and Paraguay. In Venezuela and Nicaragua, where left-identified governments managed to stay in power, it happened through an authoritarian turn.

The return to power of the right wing—and in Brazil and Bolivia, the far right—was abbreviated. Given that neoliberalism has been exhausted as a viable economic project and the Right offered no policy alternatives except a return to the neoliberal status quo, their administrations were characterized by repression, polarization, or, as in Brazil, an outright slide toward fascism.

The current spate of left governments almost universally enjoy only slight majorities or control over just the executive branch. This has necessarily moved Chile’s Gabriel Boric, Brazil’s Lula, and Argentina’s Fernández towards the center as their countries’ multi-round electoral systems meant they had no choice but to reach beyond their political base to win at the polls.

Lula’s vice president, center-right former governor of São Paulo, Geraldo Alckmin, is a case in point. Although Lula governed successfully before without congressional support, his ability to negotiate across ideological lines again will be tested. Such skills will also be necessary for left leaders in other parts of the region, but the quest to negotiate will inevitably dilute their progressive agenda. Impasses and stalemates are likely. With governments facing powerful interests of capital and pressures to make concessions, social movements must stay mobilized to push for progressive change.

This issue of the NACLA Report considers the options and challenges for Latin America’s current left-oriented governments, which are generally perceived to face far more limitations than their predecessors. What did we learn from the Pink Tide and what lies ahead for this latest resurgence of the Left, whether in the presidential palaces or in the streets? Unlike a decade ago, prices of the primary commodities that make up the region’s chief exports are more volatile. In some countries, economic growth has dropped to a trickle as global recession looms and the Covid-19 pandemic has taken a toll. Geopolitical shifts away from U.S. hegemony require successfully playing off the often indirect global competition between Washington and Beijing.

At the same time, the Right is both emboldened and more conservative. The failure of the draft of Chile’s radical new constitution to achieve ratification demonstrates the right wing’s willingness to deploy fake news and other maneuvers to block progressive efforts. While the Constitutional Convention may have overreached beyond what most Chileans could easily embrace, the right wing effectively spread disinformation, such as about what plurinationalism would mean for Chilean national unity and identity. As Luis Herrán-Ávila highlights in his article in this issue, the far right lurking in the wings behind the new left governments in many Latin American countries is not only growing but also highly strategic.

Amid these adverse conditions, success for the new left governments will depend in no small measure on greater regional coordination, something stressed by the earlier Pink Tide governments with initiatives like the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). But, as Ociel Alí López explores here, with China the main trading partner of Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, and intraregional trade reduced since 2008, these initiatives have less priority for many leaders today.

Nonetheless, important signs exist that improved cooperation is moving forward from the back burner. For the second time since 2017, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), founded in 2010 to facilitate a Latin American voice independent of the U.S.-dominated Organization of American States (OAS), met at the end of January in Buenos Aires. The hiatus had been provoked by former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s departure from the body, as the absence of the region’s largest economy effectively stymied collaboration. Lula’s government returned with proposals for closer regional ties, particularly with Argentina, including strengthening the Southern Cone trade bloc MERCOSUR and reviving UNASUR.

In its relations with the region, China prioritizes trade and investment. While U.S. free trade agreements now stretch down western Latin America from Mexico to Chile, Washington also continues to emphasize immigration and the War on Drugs. Colombia’s Gustavo Petro has harshly criticized the disasters of the drug war, but how his government will respond in practice to the U.S.-financed, 40-year-long failed strategy remains to be seen. Aura María Puyana and Sandra Bermúdez write in this issue that they are not optimistic that Petro will be able to move much further than rhetorical flourishes. Rather, they argue, his government will likely be limited to what they call a “flexible prohibitionism.”

Despite these limitations, optimism runs high among many of those entering office for the first time, as Michael Fox’s interview with Brazilian activist Rosa Amorim amply demonstrates. She was elected the youngest member ever of the Pernambuco state assembly on the Workers’ Party (PT) ticket. Amorim’s perspective, coming from one of Brazil’s poorest states, is balanced with realism about the difficult road ahead in confronting the powerful rural elites that have long dominated local politics, frequently by force.

Similarly, an interview by Virginie Laurent and Bret Gustafson with leaders of Colombia’s oldest Indigenous organization, the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC), reveals the cautious hope Indigenous peoples in the country hold about engagement with the new leftists in power. Yet even if the first left government in Colombia’s history is itself a major victory for the social movements that mobilized in the election campaign and they recognize how difficult it will be to achieve fundamental change, these leaders absolutely refuse to back down from their demands.

These perspectives highlight how achieving left-wing goals depends on instituting reforms that weave into traditional social justice issues centered on wages and poverty, feminist priorities, environmental protection, and increased minority rights. In a comparative analysis of the situation of Mexico and Brazil’s workers, Jana Silverman and Laura Macdonald explore what labor movements have accomplished, their critiques of left governments, and where the obstacles to expanding workers’ rights in each country still lie.

The tensions between social movement agendas and the region’s current left-identified governments comes more clearly into view in Dawn Paley’s interview with two Mexican feminists. Their discussion reveals the difficulties of navigating President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s disdain for radical feminists while struggling to reduce violence against women and trans people. The Left, of course, is not limited to the Left in power. As Kirwin Shaffer describes in his analysis of Latin American anarchist history, anarchists contend that the fundamental notion of capturing state power is the crux of progressive governments’ problems. During the first Pink Tide and in the latest version, building grassroots power remains a decisive horizon of struggle.

One of the leading leftist critiques of the first Pink Tide was its dependence on extractive industries to finance significant expansions in social services and public infrastructure. In his article about the financialization that accompanied neo-extractivism during the first Pink Tide, Angus McNelly argues that this led these governments to reproduce one of the central tenets of neoliberalism. Today’s left governments have an opportunity to shift from extractivist development to a more sustainable paradigm that curbs environmental harms through marshalling public investment for a speedy green transition—a Latin American version of a Green New Deal.

But with most government revenues heavily dependent on commodity rents, any drop in this income will likely hamstring government public and social investment and shorten the Left’s tenure in government. Maristella Svampa explores this dilemma, contrasting Argentina’s continued commitment to the neo-extractivism of the first Pink Time with the commitment the Petro-Márquez government in Colombia has made to what she calls the “ecosocial transition.” She cautions that while this process will be far from easy, it is essential to the health of the region and the planet.

It remains to be seen if and what the new round of left governments can learn from the lessons of the first Pink Tide and push forward progressive change while also confronting challenges ranging from environmental degradation to citizen security. As the Right continues to deploy tactics aimed at destabilization and U.S. militarism, with its talk of threats from China and Russia, threatens a new era of Cold War-style interventionism, progressive social movements will be crucial sources of support and pressure from below.

This new round of left governments will most likely be shorter, more moderate, and stormier than the first. Nonetheless, what these governments manage to achieve in advancing rights and reducing the chokehold that extractivism has on much of the region will shape the agenda for what progressive politics in the region can achieve decades from now.

Linda Farthing is an independent scholar and journalist. Her latest book is Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia (Haymarket, 2021). She has also written for The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The Nation, Latino USA, and World Policy Review.

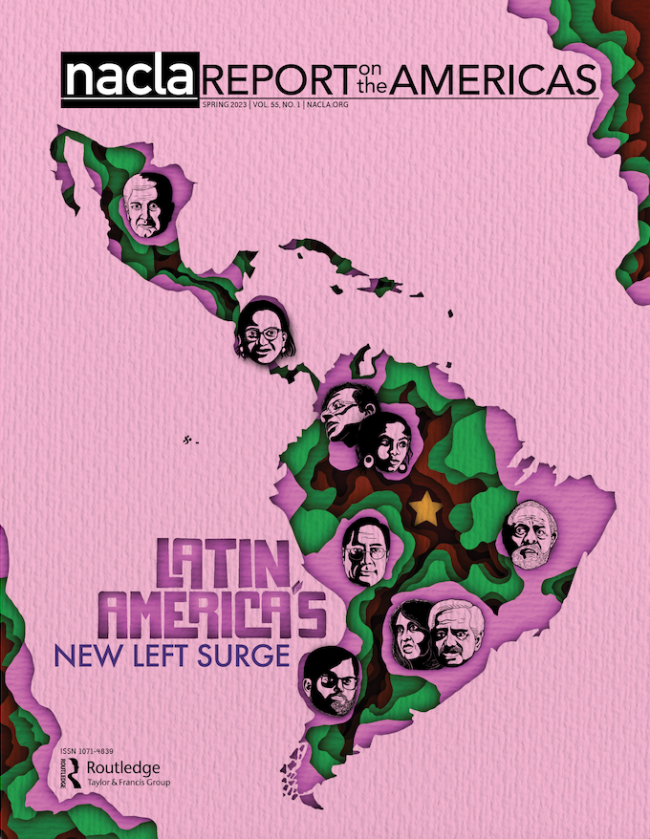

Cover art by Pedro Rodríguez García | Instagram: @p3dro_ro