“Terrorists are not only those putting bombs,” charged Argentine president Cristina Kirchner in her September 24 address to the UN General Assembly in New York, but are “also those who cause misery, poverty and hunger.” Her bellicose words on the world stage were fueled by the June 2014 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of holdout hedge funds that pushed Argentina into the ambiguous territory of a “selective default”—a characterization that the Kirchner administration vehemently rejects.

Kirchner’s hard line against holdouts—who demand repayment at the face value of bonds they bought on the secondary market after Argentina’s 2001 default—reflects growing international calls for changes to sovereign debt markets. Her harsh words at the UN, for example, came on the heels of the General Assembly’s September 9 approval of a resolution for the creation of a multilateral convention on debt restructuring, which passed by a vote of 124 to 11, with 41 abstentions. The United States and Germany were in the small minority voting against the resolution. Diplomatic spats quickly followed. Argentina’s Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman admonished the U.S. ambassador for characterizing the debt dispute as a “default,” while Kirchner’s cabinet chief Jorge Capitanich accused Germany of having a “hostile attitude” to Argentina’s debt restructuring.

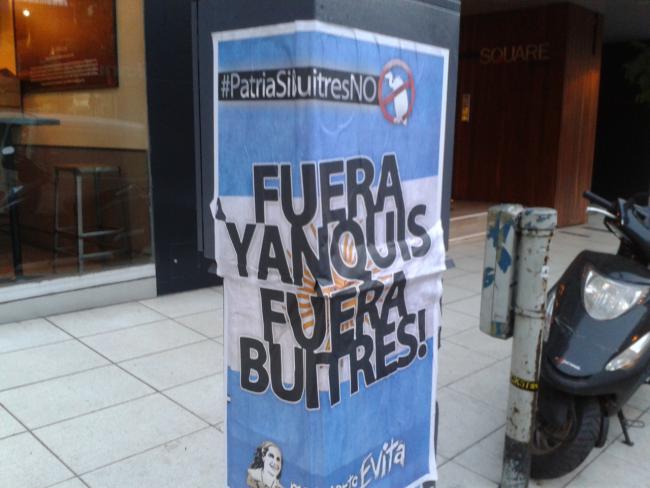

Argentina’s dispute with “vulture funds” and the U.S. courts has thus galvanized international support, highlighted geopolitical fault lines in the global financial order, and is shaping the political landscape in the run-up to Argentina’s October 2015 general election.

Support for Argentina’s initiative to create a multilateral debt convention was on display at a meeting on October 27 of the UN Third Committee in New York, for example, where Argentine human rights lawyer Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky presented a report on the effects of foreign debt on human rights. The lengthy statement in support of Bohoslavsky from the Chinese delegation was also noteworthy. Stressing the need to create a debt convention to avoid a repeat of Argentina’s dispute with holdouts, the Chinese delegation also pointed to its own record of providing interest-free loans and debt relief to developing countries.

Indeed, China’s financial support highlights the possibility that the backlash against hedge fund litigation may precipitate fundamental changes in the role of the U.S. dollar and the location of New York in sovereign financing. Currently, about 70% of the sovereign bonds issued by all governments in the world are issued in New York. But, according to research economist Michael Hudson, the case between Argentina and the nexus of New York hedge funds and U.S. courts has “really divided the world into two halves” by suggesting that any country that has issued bonds on the New York market may not be able to renegotiate their debt.

Parallel to its dispute with vulture funds and the U.S. courts, the Kirchner administration has therefore understandably deepened its alternative sources of financing through a series of bilateral agreements. Its July deal with China, for example, included the latter’s multibillion-dollar investments in two hydroelectric dams and a railway project, plus an $11 billion swap agreement between their central banks that would allow Argentina to buy Chinese imports in Yuan. Moreover, Argentina—with the second largest shale gas reserves in the world—is discussing an estimated $1 billion investment by Russia’s state-owned Gazprom to help develop its Vaca Muerta deposits in southern Neuquén province. The potential natural gas deal comes in the heels of their July agreement on nuclear energy cooperation.

Shut out from international capital markets since its 2001 default, the Argentine state is nevertheless financing infrastructure and energy projects and managing to keep its foreign currency reserves from being totally drained, all while dramatically lessening its reliance on direct foreign investment and Washington Consensus lending institutions such as the IMF and World Bank. In fact, this relative distance from international capital markets provided Argentina some measure of insulation from the worst effects of the 2007 financial crisis, which then newly elected Cristina Kirchner acerbically described as the “the First World … popping like a bubble.”

Her administration’s alignment in the wake of the U.S. court decision is further linked to wider shifts in global North-South relations. Also in July, the BRICS countries launched the New Development Bank (NDB) at their 6th summit in Fortaleza, Brazil. Set up as an alternative to the IMF and World Bank for funding infrastructure and development projects, the NDB establishes Shanghai as a competitor to New York and London in the world of sovereign financing. Its long-term effects remain to be seen, and its importance may be interpreted in terms of whether it actually breaks from neoliberal lending practices or simply disrupts their stranglehold by Washington Consensus institutions.

In any case, UN debt conventions, bilateral deals, and the launch of the NDB do not solve Argentina’s deeper problems with the U.S. dollar. While the “convertibility system” of the 1990’s that pegged the peso to the dollar and led directly to the collapse and default of 2001 is no more, Argentines are feeling the intensified dollarization of the economy that it facilitated more acutely than ever. U.S. dollars are now estimated to circulate through the Argentine economy at an all time high and the second highest per capita rate of any country in the world (behind only the United States itself), equaling nearly 40% of GDP.

Many of these dollars, moreover, circulate outside the formal economy. This has been dramatized most prominently by the phenomenon of the blue dollar—an unofficial dollar exchange with rates updated regularly in Argentina’s financial press (as well as on Twitter). This exchange of dollars above the official rate is stoking fears that it could precipitate another devaluation of the Argentine peso, after the January 2014 devaluation that was the largest since the 2001-02 crisis. After peaking in late September, the blue dollar rate has been falling recently, especially in the wake of the Kirchner administration’s crackdown on these unofficial dollar exchanges, as well as on multinational corporations and banks for alleged tax evasion. Despite these measures, the threat of capital flight remains a structural reality for Argentina.

The Kirchner administration is thus preoccupied with this massive stock of dollars over its potential for use in speculative attacks on the Argentine economy. Kirchner’s cabinet chief, Jorge Capitanich, warned earlier in 2014 of attempts at the kind of “market coup” that ousted the first democratically elected president after the end of the last dictatorship, Raul Alfonsín, in 1989 and opened the path for the Carlos Menem administration to introduce the convertibility plan that brought on the 2001 crisis in the first place.

In this context, the dispute with hedge funds has become tied up with the fate of Kirchnerism as Argentina moves towards a pivotal general election in just under a year. Sovereign debt restructuring has been at the center of successive Kirchner administration visions of “national capitalism” since 2003. It also intersects with the Kirchnerist goal of prosecuting leaders of the 1976-83 dictatorship, who had enjoyed immunity until 2006. Thus, the initiative of the center-left Unión Cívica Radical (UCR) party to create a commission to investigate the debt going back to the dictatorship no doubt reflects the fact that it was the architect of dictatorship economic policy, José Martinez de Hoz, who agreed to shift the jurisdiction of Argentine debt to New York and denominate it in U.S. dollars in the first place.

However, despite the centrality of debt restructuring to Kirchnerism, Cristina’s 2008 attempt to channel some of the profits from Argentina’s soy boom towards payments on the foreign debt via an export tax starkly revealed the limits of national capitalism. In the battle that erupted with the powerful rural interests, then Vice President Julio Cobos cast the deciding vote against the export tax law and opened a split in the administration amid mass demonstrations both for and against the government.

By 2013, Kirchner’s inability to redirect economic dividends—dramatically revealed by the failed attempt to finance debt repayment via export taxes—contributed to the dismal showing in mid-term elections by her Front for Victory electoral formation, which lost more than 20% from just two years earlier in gaining only 33% of the vote. The results stalled any thoughts Kirchner had of seeking a third term via constitutional amendments and strengthened her opposition on both ends of the political spectrum. Right-Peronist Sergio Massa and his Frente Renovador (Renewal Front) party took Buenos Aires province in the Congress, while far-right mayor of Buenos Aires Mauricio Macri strengthened his position against Kirchner’s Front for Victory, which came in a distant third in the capital city. The Trotskyist coalition Frente de Izquierda Trabajadores (FIT), or Workers Left Front, meanwhile, also benefited by winning almost six percent of the overall vote, netting it three national deputies in Argentina’s lower house of Congress.

Potential presidential candidates for 2015, meanwhile, include Macri, Massa, Buenos Aires governor Daniel Scioli, and possibly Kirchner’s chief of staff Capitanich as her intended successor. The former three have all expressed the need to resolve the standoff with holdouts through a negotiated settlement though without offering much detail on how they would actually conduct such negotiations, and have generally refrained from criticizing Kirchner’s hard line.

Looking forward, the international plane shows building momentum for changes to the way sovereign debt works. Together with the G77+China group initiative to create a multilateral legal framework through the UN, the IMF supports reforms to sovereign debt restructuring, and the International Capital Markets Association changed its sovereign bond contracts in the hopes of avoiding a repeat of the type of hedge fund litigation being conducted against Argentina. Prominent economists including Joseph Stiglitz and Nouriel Roubini have excoriated hedge fund litigation and the U.S. court decisions. Meanwhile, the United States finds itself isolated on the issue, especially relative to its Western hemisphere neighbors. On the domestic plane, the debt dispute will likely continue to have a powerful effect on the electoral landscape in the run-up to Argentina’s October 2015 general election, whatever the results.

Charles Dolph is a PhD student in anthropology at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York. His research currently focuses on Argentina’s sovereign debt dispute and its broader connections with national and hemispheric histories of economic crisis and political violence.