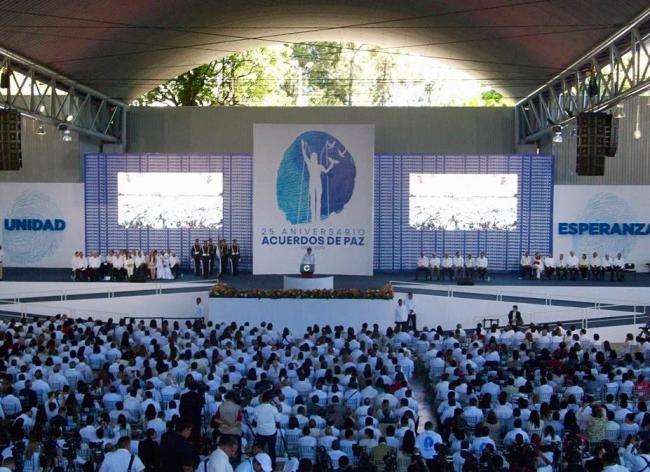

As the warm sun broke through the mist on the morning of January 16th, the San Salvador stadium quickly filled with people dressed in white and sporting their finest guayaberas (traditionally embroidered Latin-American dress shirts)—a symbolic gesture of peace for the commemoration of the 25thanniversary of the signing of 1992 Chapultepec Peace Agreement, which ended the country’s 12-year civil war.

School-age children and teenagers carrying small lunch sacks were the first to be seated. They looked on as a wide spectrum of Salvadoran society, who might not otherwise be found in the same room, joined them in the arena. Elderly folks expressed a similar excitement, dotting the crowd among social movement activists, representatives of indigenous communities, war veterans, and participants from the Yo Cambio (“I Change”) program for the rehabilitation and reintegration of incarcerated peoples.

President Salvador Sánchez Cerén, one of the former guerrilla commanders who signed the 1992 agreement with the Salvadoran government on behalf of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), presided over the event alongside other government representatives. Amidst the celebration of achievements, however, emerged a call for a “second-generation” of national agreements to address the country’s deep-rooted challenges.

The proposal comes after months of consorted right-wing efforts to destabilize the governing FMLN administration by blocking government finances, undermining democratic institutions, and an ongoing media smear campaign. If successful, the new United Nations facilitated dialogue, could bring about a truce between the rivaling political parties and other sectors of Salvadoran society as well as address the limitations of the 1992 peace treaty.

An Incomplete Peace

The 1992 UN-sponsored truce ended El Salvador’s decade long civil war between the U.S.-funded Salvadoran military and popular revolutionary armed forces (FMLN). In the months following, guerrilla combatants were slowly demobilized, and the majority of weapons were decommissioned by UN officials and destroyed. At the same time, the government dismantled its brutal state security apparatus, including the National Guard and the National Police. These groups, together with the country’s armed forces, were said to be responsible for at least 85 percent of human rights abuses, murders, and disappearances perpetrated against civilians during the armed conflict, according to a Truth Commission report assigned to investigate such crimes.

In an attempt to undermine justice and render the evidence discovered by the Truth Commission toothless, El Salvador’s legislature, under the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) party, approved the infamous and recently repealed 1993 Amnesty Law. This law provided blanket immunity to high ranking officials, as well as military and police personnel, implicated in grave human rights violations during the war.

Ultimately, the military was substantially reduced in size while constitutional reforms prohibited its involvement in politics and in public security, except during national emergencies. A new civilian police force was formed, made up of one-third former state security agents, one-third demobilized guerrilla combatants, and one-third new civilian recruits.

At the institutional level, the Peace Agreement ushered in an unprecedented democratization of many of El Salvador’s state institutions. The FMLN successfully transitioned from a guerrilla insurgency into a political party. A new institution, the pluralistic Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), was created to regulate elections and protect voter rights. The agreement guaranteed the protection of essential political and civil liberties, such as freedom of speech and association, and created the Office of the Ombudsperson for the Defense of Human Rights, an independent government institution charged with promoting and protecting human rights.

Despite these significant advancements, the Agreements ultimately failed to bring about the structural economic and social change that was at the heart of El Salvador’s revolutionary struggle. At the negotiating table, the post-conflict government would not concede to economic demands, namely the redistribution of land and wealth away from the hands of a few elite families. Following 20 years of postwar rule by ARENA and five years of governance by the FMLN, economic disparity has surpassed pre-war levels, fueled by a ruthless application of neoliberal economic policies, including the privatization of major public institutions like banks, telecommunications and electricity and the adoption of legal frameworks to privilege foreign corporations. El Salvador’s minimum wage is second only to Nicaragua as the lowest in Central America.

As if that weren’t enough, two decades of impunity, displacement, and family separation have created an environment of increased violence and insecurity that has caused tens of thousands to flee the country.

Recognizing the challenges that El Salvador continues to face, President Sánchez Cerén announced a new round of UN-facilitated accords between the government and the country's various political powers and social sectors just a few weeks ago. “In 2017, we will promote a new dialogue to achieve a second generation of agreements in the face of the current needs and challenges and move closer to that country that we dream about,” he said.

Threats to Peacetime Democracy

In recent years, right-wing political parties and institutions that represent the interests of the Salvadoran oligarchy have attempted to undermine the very democratic processes the Peace Agreement ushered in. Since 2009, they have employed a variety of tactics to erode support for the government—from organizing media smear campaigns to withholding of legislative votes aimed at blocking funding destined for social programs and security initiatives.

These actions have prompted popular social movement organizations to take to the streets to denounce opposition efforts as a “soft coup,” which they claim are intended to oust the FMLN prior to the 2018 legislative and 2019 presidential elections. Scholars and researchers have noted a growing trend throughout Latin America of “soft” or “parliamentary coups.” Unlike a traditional military coup, this strategy involves an opposition party’s use of dubious legal means, or “a fig leaf of legality,” as Kregg Hetherton and Marco Castillo write, referring to the case of Paraguay, to justify ousting a leader or party before they are constitutionally up for a vote to leave office.

Key to the Salvadoran right-wing’s strategy is the Supreme Court, which is waging a war on two of the country’s principal democratic institutions: the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and the Legislative Assembly.

After decades of quietly rubber-stamping ARENA government action, the Supreme Court, and especially four magistrates in its five-member Constitutional Chamber, roared to life following the election of Mauricio Funes in 2009, the first candidate from the FMLN to advance to the presidency in El Salvador.

In seeming reaction to Funes’ electoral victory, the Chamber issued ruling after ruling on the electoral process, effectively re-writing entire swaths of the electoral code that had been painstakingly hammered out through the country’s peace negotiations and pluralist legislative debate. The changes allowed candidates to run independently for office rather than running on a traditional vote-by-party slate. The cumulative impact of these revisions was to water down the power of political parties at precisely the moment when the left-leaning FMLN had become the most popular party in the country. As FMLN legislator Jacqueline Rivera explained at a 2012 popular movement forum, “As soon as the FMLN wins through the electoral system, you’re telling me the electoral system no longer works? No way.”

Despite the shifting parameters, the FMLN prevailed again in the 2014 presidential elections. The Constitutional Chamber then turned its attention to the country’s highest electoral authority, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), where they stripped political parties of their ability to participate and thereby maintain oversight over the process.

In June 2014, the Chamber issued a ruling that Eugenio Chicas of the FMLN could no longer serve as President of TSE on the grounds that his election to that position in 2009 was unconstitutional, despite the fact that it followed the same protocol that had been in place for decades. El Salvador’s Constitution gives the political party that won the most votes in the presidential election, which in 2009 was the FMLN, the right to nominate the TSE President. Prior to 2009, ARENA party leaders openly held the TSE presidency; Chicas’ predecessor, Walter Araujo served not only as an ARENA parliamentarian but also briefly as president of the party itself.

However, after the FMLN’s second presidential victory in 2014, the Constitutional Chamber ruled that TSE magistrates could not have political affiliations. New magistrates were elected after the ruling in time to oversee the 2015 legislative and municipal elections; however, in recent weeks, the Chamber announced it would accept a case against TSE Magistrate Ulises Rivas for some comments made in support of the FMLN’s candidates, despite the fact that he is not a member of any party. Rivas is now seeking protective measures from the Inter-American Human Rights Commission of the Organization of American States.

The Chamber has also targeted the Legislative Assembly, El Salvador’s most representative democratic institution. In July 2016, they announced a set of controversial rulings that popular movement leaders and the FMLN denounced as an attack on both the executive and legislative branches of government. The court declared unconstitutional the emission of $900 million in government bonds that the Legislative Assembly had approved the year before and halted a 13 percent energy tax increase intended to finance renewable energy.

Most alarmingly, however, is that in order to justify its ruling to block the emission of $900 million in bonds, the Constitutional Chamber issued a subsequent ruling that dramatically re-shaped the legislature itself. The close legislative vote to approve the bonds included votes from substitute deputies, who are elected alongside congressional representatives to fill in when the principal or proprietary deputy is absent. Substitute deputies are referenced in the Salvadoran Constitution, which gives the Legislative Assembly the power to call upon substitutes in the instances of “death, resignation, annulment, temporary absence or impossibility of attendance of the proprietary deputy.” Despite their explicit mention in the Constitution, and the fact that the Legislative Assembly vote to elect these magistrates to the Supreme Court included fourteen substitutes voting, the Chamber ruled them unconstitutional and stripped them of their titles overnight, throwing the legislature into a temporary crisis.

Popular movement leaders decried the Supreme Court ruling as an attack on the autonomy and structure of the legislature and accused the Court of acting as a “political instrument of destabilization against the government.” During a July rally outside the Supreme Court, representatives of popular and social movement organizations told the press, “We call on the magistrates [of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court] to stop their political maneuvers disguised as judicial rhetoric, which … are at the service of powerful oligarchy groups. Their actions have converted the Chamber into a political instrument of destabilization against the government.”

Human rights organizations and diverse voices from other social movements joined the union federation and campesino organizations in denouncing the Supreme Court magistrates and calling for their resignation. Immediately following the ruling, the Social Alliance for Governability and Justice (ASGOJU) spoke out against the rulings as interfering with the responsibilities of other branches of the government. According to Margarita Posada of the National Health Forum, “The rulings are true attacks on the institutionalism of the country.”

In the face of growing outcry, the Salvadoran elite turned to international allies for protection, presuming correctly that the independence of the judiciary would be upheld even in the face of mounting evidence that the magistrates are acting in violation of their jurisdiction and Constitutional mandate.

In late September, members of Aliados por la Democracia (Allies for Democracy), a conglomerate of right-wing organizations, think-tanks and private business interest groups that has received funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), called on the Organization of American States (OAS) to declare its opposition to the “attacks suffered by the Constitutional Chamber [of the Supreme Court] on behalf of the government, and groups and movements associated with the FMLN party.” Both the OAS and the UN responded in favor of the Court, lending legitimacy to this political maneuver.

Over the years, the U.S. Embassy has also weighed in on these internal political disputes to defend the Supreme Court. In 2013, former U.S. Ambassador Mari Carmen Aponte said that “the Constitutional Chamber’s decisions should be respected;” otherwise, U.S. development cooperation, namely, a $277 million Millennium Challenge Development pact, would be in jeopardy.

Despite the external pressure, there is growing consensus in El Salvador that the five-member Chamber has strayed far afield of their constitutional mandate and that their judicial activism represents a dangerous abuse of power. According to Marielos de León of the Coalition for a Safe Country without Hunger (CONPHAS), “The four magistrates of the chamber today want to deliver rulings, legislate and govern in this country … [But] government in this country [is constituted by] mayors, legislators, and the president, because we popularly elected them.”

The face-off between El Salvador’ democratically-elected government and the Supreme Court has echoes of the 2009 coup against President Zelaya in Honduras and the 2012 ouster of President Lugo in Paraguay. As many Latin American countries “turn right” and elites consolidate new strategies to undermine democratic progressive governance, El Salvador’s revolutionary leadership and popular social movements are now organizing to defend the institutions that were won and shaped by their struggle 25 years ago. As Norma Ramos, coordinator of Movimiento Popular de Resistencia MPR-12 (Popular Resistance Movement) reminds her fellow organizers, “These achievements, they have cost us blood, they have cost us 12 years of war.”

Alexis Stoumbelis is Organizational Director with the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador in Washington, DC (CISPES).

Samantha Pineda is a researcher on political and social issues currently based in El Salvador. She is a graduate from the University of California-Santa Cruz in Feminist Studies and Latin American and Latino Studies.