A year after President Trump's inauguration, our worst climate policy nightmares have become a reality. Fossil fuel interests have hijacked every part of the new administration—the State Department, Department of the Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, and the National Economic Council—and the list continues. The intensity of global-warming fueled devastation increases daily as over a century of fossil-fueled war and violence against labor and nature rages on. Latin America is familiar with this kind of violence.

As hurricanes rip through the Caribbean and tear into Central America, it would seem common sense to acknowledge the ills of fossil fuel dependence and mobilize for radical transformation. Yet Latin America and the Caribbean have long been subjected to the oil-dominated foreign policy and military interests of the United States. And, as we have seen in Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, and Bolivia, even resistance to this imperialist project has long depended on oil in its increasingly deep and dangerous iterations.

Today, the progressive turn of the early 2000s is sliding backward toward a more familiar politics dictated by capital and the hyper-militarized right, one long committed to monetizing any and all subsoil resources for the sake of accumulation, planet be damned. Extractivism has become a familiar debate in the past decade, which we engaged in the spring 2013 issue of the NACLA Report. But the particularities of fossil fuels—and the ambiguities and contradictions they raise for political projects and visions on both right and left—begs closer examination. Might activists and thinkers on the left find a way to envision political projects that transcend a long-standing dependence on the idea of oil nationalism and oil sovereignty? Facing the retrenchment of the right as they deploy tools old and new—from TV media to militarized police—to deepen and expand the extraction of oil and gas, how are affected communities responding? These are the dilemmas we explore in this issue.

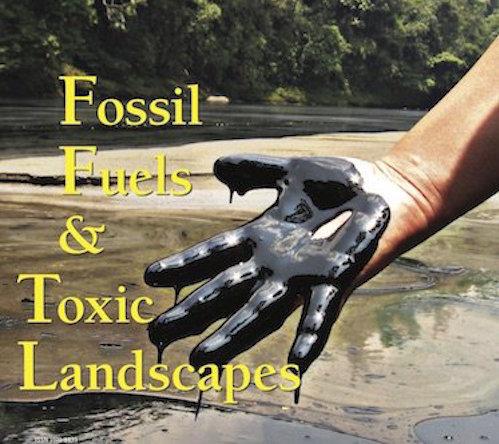

Oil and gas expansion, and resistance to its effects— from physical displacement to destroyed landscapes to livelihoods subjected to poisoned air and water—continue to characterize the region. Lorena Riffo's piece on fracking in Argentina takes us close to the ground. Today, Argentines are grappling with the legacies of Indigenous genocide and the seductive lure of oil sovereignty and right-wing nationalism to confront the new scourge of fracking, implemented in the name of solving the country's energy crisis.

From Brazil, Alexandre Araujo Costa makes a bold challenge to the left: “Yes, the oil is ours, and we should keep it in the ground!” This is perhaps a quixotic dream but nonetheless a concrete point of struggle, increasingly linking peoples across the Americas. Bryan Parras brings the point home to Houston, Texas in his interview exploring the racialized dimensions of the chemical industrial complex. In the wake of another devastating storm, beleaguered communities of Mexican-Americans yet again confront the seemingly unassailable power of the oil industry and the painful realities of living and dying in toxic landscapes. As these areas become increasingly toxic due to worsening climate disasters and environmental racism, heightened displacement and emigration will certainly follow, as Todd Miller explores in his book Storming the Wall, excerpted in this issue. Rather than seek out more sustainable policy, governments have instead turned to increasing border securitization and technology to fight threats of growing immigration due to environmental disaster.

To read the rest of this article and content from this issue, click here.