The death of a pop star often has a way of breathing new life into her fans. On March 5, 1995, Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, a 23-year-old Tejana singer of rising fame, was murdered by the president of her fan club at a Days Inn motel in Corpus Christi, Texas. In the following days, as many as 60,000 fans, mostly Mexican, drove to her Corpus Christi hometown to pay their respects. Five months later, 619 newborn babies in Texas had been given the previously uncommon pop star’s name. Selena’s techno cumbias and accordion-filled polkas played around the world, from remote Mayan villages in Guatemala to the bedrooms of teenage girls in the Netherlands.

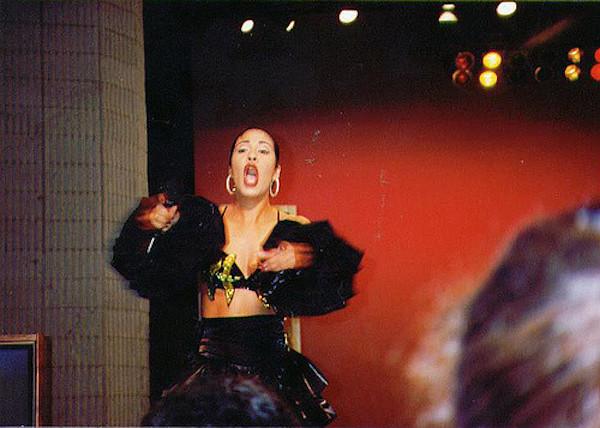

If Selena were still living, she would have turned 47-years-old today. Yet in her death, she is more celebrated than she ever was in life. She is simultaneously considered a repository of Latina sexuality and purity, a working-class heroine, a multi-million dollar industry, an LGBTQ icon, and the subject of academic debate. "Selena's a complex role model," said the filmmaker Lourdes Portillo in her 1999 documentary Corpus: A Home Movie About Selena. "On the one hand, she gave girls a lot of confidence about who they were. On the other hand, the way that she went about doing that was to be very showy and very sexual, which is not really accepted in our culture."

Last year, thousands of Selena fans and impersonators, from Brooklyn to Chicago to Oakland, attended Selena dance parties, sing-a-longs, drag shows, festivals, painting parties, screenings, and lectures, with names like “Noche de 1000 Selena” and “Fiesta del Flor.” In 2016, MAC Cosmetics released a Selena collection, after a Change.org petition received 37,000 signatures from her fans. Sultry lipsticks named after her hit songs “Dreaming of You” and “Como La Flor” sold out globally. On October 17, 2017, Google dedicated its homepage “doodle” to “Celebrating Selena Quintanilla.” Most recently, ABC announced a forthcoming Selena-inspired family drama television series.

Crossing Over

Selena was born in Lake Jackson, Texas, a working-class exurb of Houston, in 1971. Her parents were Jehovah’s Witnesses. In the early ‘80s, Selena’s father left his job at a local chemical plant to open a Mexican restaurant Papa Gallo, where Selena, who did not yet speak Spanish, sang in English for customers. The restaurant floundered, but Selena charmed her audiences. She dropped out of high school, hitting the road in the family’s beat-up bus. "We went through a hard time, and we had to turn to music as a means to putting food on the table,” Selena told a reporter in an interview in 1995. “We've been doing it ever since. No regrets either."

Selena soon garnered a reputation as the Queen of Tejano music—a Texas borderlands genre that mixes cumbia, corridos, and conjunto with pop and rock. She spent her teenage years performing at show grounds and concert halls across Texas, and eventually in northern Mexico. At 20-years-old, and much to her father’s disappointment, Selena eloped with Chris Perez, her guitarist. Selena’s father grappled with his daughter’s image even after her death. “She was a genuinely good person. She was clean. She stood for family,” Abraham Quintanilla said of his daughter.

Just months before her death, over 60,000 people attended Selena’s final concert at the Astrodome in Houston, where she wore her iconic sparkling purple pantsuit, riding atop a horse-drawn carriage and singing Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” and Donna Summer’s “Last Dance,” part of a strategy to crossover into the mainstream U.S. market.

Selena’s posthumous popularity finds its roots in the fraught history of U.S.-Mexico relations. In the years since Selena’s death in 1995, the Latinx population in the United States has more than doubled from 27 million in 1994 to 58 million in 2016. The majority of these Latinxs have roots in Mexico. Their migration can be linked to passage of the 1994 North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) that displaced millions of campesinos, from plots of land in southern and central Mexico, forcing them to migrate to larger Mexican cities and the United States in search of work.

A vicious deportation regime ensued, backed by voters and championed by every U.S. president from Bill Clinton to Donald Trump. Around the time of Selena’s death, California voted to pass Proposition 187, a law that would have banned undocumented immigrants from accessing public services, like healthcare and public schools in California. In 1996, President Clinton enacted the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), building up the border fence and expanding the list of deportable offenses to include minor crimes like shoplifting. Near the time that Selena’s assassin Yolanda Saldívar received a life sentence for first-degree murder in a Texas courthouse, a wave of femicides broke out south of the border in Ciudad Juárez, inciting fear in Texas border communities. Nearly 400 young women, many of them teenagers, in Ciudad Juárez were brutally raped and murdered between 1993 and 2008—most with impunity.

While Mexico spiraled into a long and bloody drug war, Latinxs became a major economic force in the United States, with spending power that now outpaces Mexico’s GDP at $1.4 trillion. At the same time, Latinx popular culture merged into mainstream U.S. markets, and Selena remained in the limelight. "She was the first one to hit everybody's soul at the same time: the Puerto Rican community, the Mexican community, the Chicano community,” said Vincente Carranza, a Corpus Christi radio host. “When she died, she became part of our soul."

A Thousand Women Become Selena

On the first anniversary of Selena’s death in 1996, Warner Brothers announced an open casting call for the biopic Selena. 80,000 calls immediately flooded a 1-800-SELENA hotline, and over 24,000 women and girls—Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Guatemalan, and Honduran— appeared on stages in Chicago, San Antonio, Los Angeles, and Miami to try their hand at playing the role of Selena. “It was a decidedly surreal scene,” reported the Houston Chronicle. “Skinny Selenas, chunky Selenas, Selenas in gold lamé, black lace Selenas, cap-wearing Selenas, dressed-down Selenas.” To the dissapointment of many of her Chicana fans, an unknown 27-year old Puerto Rican actress named Jennifer Lopez was selected for the role.

As was clear by the number of women who hoped to become her, Selena’s music resonates with many audiences, but perhaps none more widely than Latina preteens and teenagers. Her upbeat “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” and “Baila Esta Cumbia” are classic quinceañeras songs, while the more reflective “Amor Prohibido” (Forbidden Love) and “Dreaming of You,” are meant to be listened to alone in a state of longing. “There's nowhere in the world I'd rather be/Than here in my room dreaming about you and me,” Selena sings in “Dreaming of You.” Her lyrics tend to focus on the possibility of being in love rather than its actualization, and she is always good-hearted. The 1992 hit “Como La Flor,” is about the revelation that a lover has met someone new, but nonetheless, Selena wishes them the best: “Si en mí, no encontraste felicidad/Tal vez, alguien más te la dará.” (If you didn’t find happiness with me/Perhaps someone else will give it to you.)

Female pop stars often occupy tenuous territory for feminists—and Latina intellectuals have debated the merit of Selena as a role model. "Selena gave these girls a way to have Chicana sexuality," said the writer Cherrie Moraga in the documentary Corpus: A Home Movie About Selena. Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street, is more pessimistic. "I'm not a Selena fan," Cisneros responds to Moraga. “The fact that the only outlet that you have is to be this sexual being singing songs that aren’t even that wonderful, and that you have to die before you are 25 and that makes you successful?”

Yet by today’s parameters, Selena stands out as neither sexually empowered nor sexually objectified. Especially when compared to those who followed her—Jennifer Lopez, Christina Aguilera, Shakira, Selena Gómez (who was named after Selena), and Camilla Cabello. It seems, at least, that Selena’s legacy in the ‘90s helped the music industry open the floodgates for the hyper-sexualization of Latina pop stars in the twenty-first century.

I had never heard Selena’s music when I first saw the movie Selena in sixth grade, though I was familiar with Jennifer Lopez, who stars as Selena. Like many non-Latinxs who grew up in the '00s in parts of the country with large Latinx populations, I learned about Selena in school. One day my Spanish teacher in southern California rolled out a TV set in front of the class, and put on Selena.

Many of my classmates, myself included, were deeply upset and moved by Selena’s story. The film adopts the light-hearted and slapstick tone typical of ‘90s family comedies. But it ends traumatically with Selena being gunned down by Saldívar, the president of her fan club, who Abraham Quintanilla had caught embezzling money. No one expected Selena to die. That evening, I went home, downloaded Selena on my iPod, and locked myself in my room. Thirteen years later, I haven’t stopped listening to her.

Lauren Kaori Gurley is the web editor at the North American Congress on Latin America, NACLA. Her reporting on the U.S.-Mexico border, labor, rural poverty, sexual harassment, and feminist issues has been published in CityLab, In These Times, NPR's Latino USA, The American Prospect, and ProPublica.