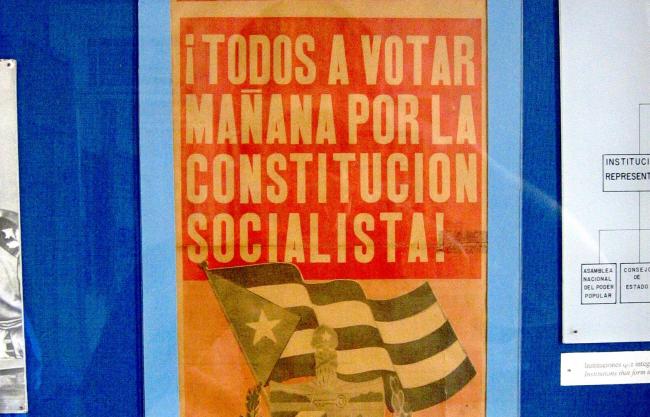

During his time as president, Raúl Castro announced a series of reforms. One of these was to overhaul Cuba’s 1976 constitution, which was drafted at the height of Cuban socialism and has long been out of sync with the country’s post-Soviet reality. In July, Cuba’s National Assembly unveiled a proposed version for the new constitution. This draft will undergo a process of public debate throughout the fall and should be ratified in February 2019.

The constitutional reform has intensified debates on the island about rights, citizenship, and the new economy. This essay forms part of a running forum NACLA is hosting to offer a range of views on this crucial process at a critical moment in Cuban history.

In this essay, lawyer Amalia Pérez Martín argues that the legal loopholes in the draft of the new constitution have political consequences. They may leave certain basic rights vulnerable, permit the rollback of the state’s social responsibilities, and facilitate arbitrary state actions.

Click to read parts one, two, and three.

The draft of Cuba’s Constitution currently under debate could open possibilities for a more democratic regime that would limit arbitrary actions of the state. Yet it also contains a number of problems from a legal standpoint, with significant political consequences. For one, it allows for the development of future laws that would clarify or alter existing provisions in the constitution without always specifying a concrete timetable for their passage. This implies that the exercise of a number of essential rights comprised in the constitution, such as freedom of the press or the right to assembly, could be weakened by subsequent laws, or not guaranteed unless followed by another law. Furthermore, the constitution defines the word “law” overly broadly—as virtually any legal directive from a government body—raising the possibility that lower, non-elected authorities could limit rights. The draft constitution should have clearer parameters of legal certainty.

Legal certainty has been theoretically defined as a constitutive principle of the law. In general, it means that the legal consequences of certain actions are clearly defined and predictable. Specifically, legal certainty endures if the law is public and accessible, reliable, stable over time, and predictable. Understandings of the notion of legal certainty have oscillated between two ideas. On one side, in the 1930s legal scholar Jerome Frank, a proponent of “legal realism,” deemed legal certainty “a myth.” On the other hand, another school of thinking argued by Norberto Bobbio deemed that “the law is certain, or it is not a law.” A more nuanced stance would say that while absolute certainty may be impossible, the degree of uncertainty tolerable to preserving the rule of law in the republic should be limited.

Advances in the field of legal certainty have been central to the so-called “new Latin American constitutionalism”—that is, the constitutions of Colombia (1991), Venezuela (1999), Ecuador (2008), and Bolivia (2009), which have expanded human rights and opened up greater space for popular control and decision-making. Cuba’s constitutional reform should be seen in this context. The draft of the new Cuban Constitution incorporates some specific provisions that provide some legal certainty, which open possibilities of more substantive citizen dispute over arbitrary state actions. These include the recognition of indivisibility, interdependence, universality, and progressive realization as mandatory principles for the exercise and protection of human rights (Article 39, 40), guarantees of criminal due process (Article 48), and judicial guarantees of constitutional rights (Article 94). Indeed, the inclusion of these rights, warranties, and principles could open possibilities for more substantial citizen dispute over arbitrary state actions. However, the multiple loopholes of the draft and the maintenance of a state structure tends towards concentrating power, detracting from its democratizing potential.

Legal certainty is a political good—this lesson is clear from history. Disputes over legal certainty have included demands for publicity and systematization of the law, but also have implications for demands for socio-economic equality and political participation. In the case of republicanism, the laws are the vehicle of citizen freedom, but only if those laws are produced by the people in the act of democratic self-determination.

However, the vague definition of “laws” in the draft constitution is a concerning sign for the future of the Republic in Cuba. According to the glossary, although the term “law” literally refers to the normative dispositions approved by the National Assembly of People’s Power, “it is also conceived in the text to refer to any type of norm regardless of the body that issues it.” In other words, laws can refer to any legal norm, including resolutions by administrative officers or decrees issued by the president—both authorities that are not directly elected by the people. In this sense, the draft continues undesirable state practices in effect since the 1959 Revolution, such as limiting constitutional rights through norms that are not approved by the National Assembly, disorganization and arbitrariness within the legal system, and increasing the distance between laws themselves and the way they are applied.

Provisioning Versus Guaranteeing Rights

Beyond the severe consequences of this lenient definition of “laws,” the draft includes a greater number of references to future laws than the existing constitution. Nearly half of the constitutional provisions in the draft contain such references, meaning an additional legal norm will need to pass to make those provisions viable. The draft constitution’s reliance on passing subsequent laws to put its provisions into effect creates patterns of uncertainty in several ways. First, the specifics of some rights and their guarantees depend on the passage of a subsequent “law.” These include the rights to exercise Cuban citizenship in national territory (Article 35), the rights to a free press (Article 60), the rights of assembly, demonstration, and association (Article 61), the right to address complaints and petitions to authorities (Article 64), the right to inheritance (Article 66), the right to free education (Article 84), the right to judicial guarantees of constitutional rights (Article 94), and the guarantees of rights to petition and to local popular participation (Article 195).

There is a history in Cuba of gaps between rights recognized in its constitution and complementary laws needed to actually guarantee those rights. In the case of the 1976 constitution, some complementary laws essential to exercising rights recognized in it were simply never drafted. This is part of the way that the state exercises its domination—through a prolonged and uncertain wait that generates routines of conformity and obedience among citizens. They learn to be “patients of the state” to survive.

Some authors have described this as a form of “unconstitutionality by legislative omission,” and have pointed out the need to conceive “legal reservations” (reservas de ley) to prevent this. In any case, the absence of these laws reveals that the National Assembly has never assumed the political centrality that it should have as Cuba’s legislative body. Those powers have continuously been exercised by the Council of State and its president instead.

Another problematic pattern is that these subsequent “laws” threaten to limit the exercise of certain rights through the introduction of future “cases” and “exceptions.” For example, the exercise of property rights and Cuban citizenship are uncertain because other laws must define “cases” of the confiscation of property (Article 58) and recovering citizenship (Article 38). The draft also allows “exceptions” and “limitations” to the rights of workers to rest (Article 78), voting rights (Article 200, 202), and freedom of movement (Article 54).

There is also significant ambiguity regarding the structure and functions of leading state bodies. Thus, for example, subsequent laws must determine the composition of the Council of Ministers, the National Electoral Council, and the National Defense Council. Similarly, the specific powers of offices crucial to keeping the state accountable, such as the Office of the Attorney General, the Office of the Comptroller General, the National Electoral Council, and the National Defense Council, are not fully defined in the draft constitution. Moreover, for state bodies in which functions are defined, as in for the Council of State, President of the Republic, and Council of Ministers, other laws can still add new functions.

Transitional Provisions

The way the constitution will come into effect, or its “transitional provisions,” also raises concerns. These provisions establish that the National Assembly of People’s Power will approve a legislative timetable of up to eighteen months from the time of the constitution’s approval to its entry into force. This is actually a better solution compared to the practice sustained since the late 1990s of having the Ministry of Justice in charge of non-public legislative timetables. However, the transitional provisions still raise questions regarding how leaving an undefined timeframe on passing complementary laws produces legal uncertainty.

To address this, the constitution itself should include a legislative timetable which includes a comprehensive list of laws and when they will be enacted, as in the current Ecuadorean Constitution. In this way, the legislative calendar would be subject to the same popular debate, consultation, and referendum. Hence, the people would influence the agenda and its priorities, a guide for governmental action and its popular control.

The 12th transitory provision provides an important example of the urgency of imposing such controls. This provision indefinitely authorizes the Council of Ministers or its executive committee to transfer all usufruct rights over public property (i.e., “socialist property of all people,” Article 23), with virtually no limitations, “pending the legal provision.” Until another law is passed to regulate it, this not only opens the possibility of the concentration of state powers, but also the transfer and accumulation of power and wealth to private and foreign sectors.

Ironically, though the draft constitution also introduces the human rights principle of “progressive realization,” its definition in the glossary as “the possibility of future recognition of rights not included at a historic moment” without a regression of those already achieved, could potentially permit to roll back the state’s responsibilities in providing social rights. Whereas the 1976 Constitution stated clearly that it was the state’s prerogative to provide access to certain goods and services, the draft constitution implies that the state will work toward providing such rights. For example, rather than a state guarantee to decent housing, the draft says that “the state works to make this right effective” (Article 82). This sense of “progression” is ambiguous and problematic because it can easily legitimize inactivity, irresponsibility, and withdrawal from the state’s responsibilities in a socialist society.

State officials, when confronted about the constitution’s lack of clarity, have argued that the constitution cannot regulate everything; it should focus only on the minimum necessary (namely, this constitution is a “norm of minimums”). Yet a constituent process is not about how much of the social world can be regulated through laws, but about the people deciding how much uncertainty our republic can allow. Defending our right to legal certainty is a weapon of struggle against state arbitrariness and the absence of guarantees to effectively exercise our rights. This certainty is not only a legal matter, but also a political imperative.

Amalia Pérez Martín is a Cuban lawyer and sociologist and author of La iurisprudentia en el derecho actual. ¿Todos los caminos conducen a Roma? (Jurisprudence in Current Law. Do All Roads Lead to Rome?) She is currently a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Merced.