Haz clic aquí para leer la versión en español.

The Escobal Mine, located in eastern Guatemala, is the second-largest silver mine in the world and the source of one of the most protracted environmental conflicts in Guatemala. Mining activities have been suspended by direct action from the community resistance movement, and by order of the Constitutional Tribunal since mid-2017.

In 2018, the Constitutional Court (CC) declared that the Ministry of Energy and Mining (MEM) had breached the Xinka Peoples’ right to consultation by awarding the mining license without considering international obligations under International Labor Organization Treaty 169. The Court ordered that MEM carry out a consultation process, which as soon as it was finished, would permit the mine to resume operations. The ruling left several key questions unanswered:

- Who should be consulted?

- What is the area of influence of the mine?

- What is the meaning and nature of the process of state-led consultation?

Of central importance is the fact that this ruling did not recognize the legitimacy of community-led consultations carried out over the past eight years, principally under municipal jurisdiction, which demonstrated overwhelming opposition to the mine in surrounding communities. A more robust concept of consultation that holds that the mine has to close definitively predominates at the local level. Since the ruling, there has been a conflict between the community conception and the meaning of consultation promoted by the mine. The two groups seek to influence the process ordered by the tribunal, forwarding irreconcilable answers to the three questions above, with distinct mechanisms at their disposal. President Jimmy Morales recently said the consultation required to restart the mine will be completed before he leaves office in January.

Sociopolitical and territorial reality is a product of an asymmetrical dialectical struggle between incompatible visions and competing strategies. The community resistance uses a variety of peaceful opposition methods: protests, public debate, appeals to logic, legal denunciations, direct action to stop mining activity, political alliance with the catholic church and national and international NGOs, and legal strategies based in Indigenous rights. They have maintained a constant blockade against the entry of mining materials since 2017, and launched a campaign to re-vindicate the Xinka identity before the 2018 census. Now, 268,223 people counted in the census identity as Xinka, up from 16,214 in 2002. In addition, they have sought assistance from scientists to conduct independent environmental impact analysis, especially studies of water.

On the other side, the mine proclaims itself as a motor of regional development and has given gifts to various affected communities in order to gain their support or silence critics. They affirm their environmental analysis, which downplays the negative effects of the mine. Before the Court ruling, they bought radio ads saying, “the Xinka people do not exist.” Even more concerning, the mine has pursued a criminalization campaign against the community resistance. In 2013, security forces attacked peaceful demonstrators with firearms, killing two and wounding 11 more. Many members of the resistance have been assaulted and threatened, or unjustly incarcerated for months. The mining company is in the process of manipulating the consultation process with the complicity of the state.

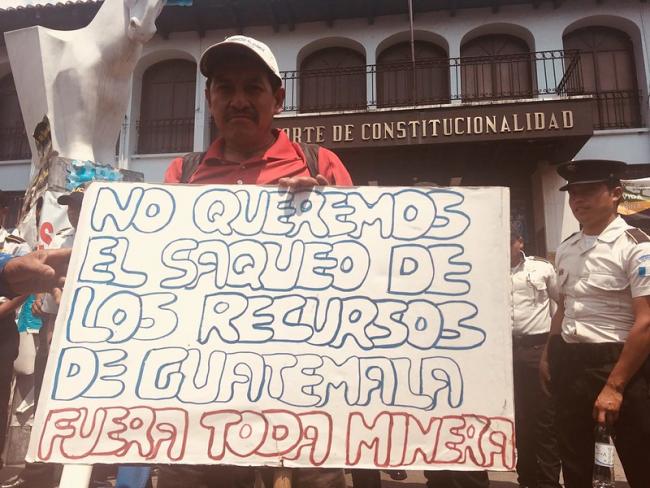

On August 8, 2019, the Xinka Parliament denounced the Ministry of Energy and Mining (MEM) and the Ministry of Natural Resources (MARN) announcement that only the Municipal Development Council (COMUDE) would participate in the pre-consultation phase, a decision that aligned with the reduced definition of the area of influence that was illegally determined before the consultation process. They began the consultation with the COMUDE representatives despite the fact that the Constitutional Court clearly stated that the COMUDES are not legal representatives of the Xinka Parliament. The Parliament urged the General Prosecutor to sue MARN and MEM for failure to comply with due process, perjury, and influence trafficking. They also appealed to the Supreme Court of Justice. There have not been adequate responses to their complaints and MEM continues to work with the reduced area of influence and without the participation of Xinka authorities. Worse still, they have augmented attacks on the resistance. August 25 was the 8th anniversary of the first consultation, but the process currently underway does not at all represent the spirit of the original. In response to the discriminatory and unconstitutional process, on September 3—the anniversary of the Constitutional Court’s decision—the resistance marched in the capital to demand their rights, affirming that if the process continues in this way, it will not have legitimacy.

A Public Investigation

The constrast between the culture of extractive capitalism represented by the mine and the alternative conceptions of the community resistance were on display in Guatemala City at the end of February 2019, when the Center for Conservation Studies (CECON-USAC) presented a multidisciplinary study of the impact of the Escobal Mine before a packed crowd. The mine’s desire to shrink the right to consultation was visible.

The CECON study, Desigualdad, Extractivsmo y Desarrollo en Santa Rosa y Jalapa, conducted by a team of five young Guatemalan professionals and financed by Oxfam Guatemala, was oriented toward the common good and human and Indigenous rights, and painted a gloomy picture of the environmental, economic, social and psychological effects of the mine, all borne by the public as externalities, and for which the mine has assumed very limited responsibility. It provided strong support for the community opposition.

Using graphs, maps, and images and guided in a multidimensional conception of poverty, the researchers detailed the failures and risks of the mine. The mine only created a small number of jobs and had a minimal effect on local poverty. The budget for the mine closure was wildly optimistic; the mine dug giant tunnels—two km—in the upper part of a watershed and a water system that is the recharge zone for a regional aquifer. Dozens of freshwater springs have dried up in villages above the mine and there is a high probability that the mine is contributing to a rise in arsenic in the regional water system.

In order to empty the tunnels to reach the silver vein, the mine consumes 255 gallons of water per minute, and 2.8 million cubic liters per year, lowering the water table and doing long-term damage to the watershed. Furthermore, the mine has led an entire village, La Cuchilla, to be condemned, such that the residents fit the UN definition of internally displaced persons. For these reasons, the study concluded that the mine has generated conflicts that have left the local population traumatized, living with stress and uncertainty. The study also criticizes MARN and MEM for not having conducted an adequate analysis of risk and failing in its regulatory function.

The study repeatedly questions the ethics and logic of installing, without previous consultation, a mine in the upper part of a watershed that is the source of water for several towns, in a region where arsenic exists in a natural form in the subsoil, such that it can easily enter into the water system due to mining activity that grinds the rock and exposes it to water and oxygen.

The mine is therefore a producer of anti-freedom, anti-development, and inequality, because it ignores integrated solutions and excludes the people from consideration. It offers gifts and jobs, but in exchange for risk, unbearable noise, harassment, division, negation of identity, massive transformation of the territory, and systematic exposure to harm. It aggravates inequality in several dimensions. This analysis could apply in good measure to many of the megadevelopment projects in Guatemala.

It is rare that a megaproject in Guatemala is submitted to an academic and scientific batter so complete and sustained by a public institution. The fact that CECON’s offices were robbed four times in January, the month prior to the publication of the study, underscores the importance of its conclusions.

Due to the fact that I had arranged for a water systems engineer from Virginia Tech, Dr. Leigh Anne Krometis, and her doctoral student, Cristina Marcillo, to conduct a monitoring of the surface water systems around the mine that contributed to the study, they invited me to the panel of commentators.

The Mine Speaks

The first comments were given by John Serna, the previous director of sustainability for Tahoe Resources, the former owner of the mine, and now with Pan American Silver—a Canadian mining company and one of the largest silver mine operators in the world—the new owners. Serna’s presentation provided a vivid example of how mining companies engage directly and publicly with organized and dedicated indigenous critics, and how this “dialogue” is part of a public relations strategy to overcome opposition. It opens a window to understanding how they insist that the world must be understood—as a strategy for the following phase of court ordered consultation, to make the world adjust to their vision.

Serna began by “accepting,” in a general and vague form, the findings: “We [the mine] share in good measure the conclusions and recommendations,” but at the same time, extolled the superiority of the mining company in the domain of science, offering to share data from 11 monitoring points generated since 2009. The clear but subtle implication was that their additional and superior data would complicate the picture beyond what had been presented by the study. Nevertheless, he affirmed that the mine was open to accepting the findings “in good part,” just as they hoped that the authors of the study, and their other critics, would be open to their data. Despite the fact that he “accepted” the criticism, he presented its findings as completely consistent with the continued operation of the mine.

Furthermore, Serna positioned the mine as an “actor in the territory” together with the Xinka “population,” with a future ahead of it, minimizing the economic and political power of the mine: “we are not really that big and powerful.” He insinuated the possibility of a better redistribution of the benefits of the mine and the efforts to “mitigate” the situation in La Cuchilla in order to “close the wounds” and begin a “process of reconciliation in the territory” so that the mine can be “part of the solution, not only a problem.” He presented the continued existence of the mine as necessary for the creation of a just and inclusive society, a vision that excluded—definitively—the possibility of closure.

A large measure of the political force of his presentation regarded what he left without saying. He never mentioned the Xinka people or the Xinka Parliament by name, an effort to predefine the consultation ordered by the Constitutional Court that they consider inside the “area of influence”. He was also careful not to mention Treaty 169 of the International Labor Organization—not even the word “consultation”—which implies Indigenous rights. He specifically invited municipal mayors to “dialogue” about the future of the region, and unspecified “Xinka populations.”

He closed his presentation with a quote from Pope Francis’s encyclical that called on humans to unite behind sustainable development, positioning the continued existence of the mine as completely compatible with this philosophy.

Critical here is that the company, although generally recognizing damages, accepted no fiscal or legal responsibility for the ecological or social harm, denied the structural nature of the problems and promised to continue mining operations. The community has expressly refused such “dialogue” and the mine for years, and furthermore those efforts are prohibited during the consultation process, undermining it as a process free from coercion for the communities.

It is impossible that the mine operate and continue to expand without consuming great quantities of water that damage the watershed ecosystem and regional economies. Beyond the risk of acid mine drainage, there are sociocultural aspects, the economic impacts, the human costs of criminalization, the demonization and violence against the community resistance. Environmental destruction and conflict are fundamental to the existence of the mine; these are not things that can be simply wished away. Those effects are incompatible with the concept of development advanced by community organizations, which focus generally on agriculture for subsistence and market, the human right to water and a healthy environment.

The members of the resistance were happy to hear the results of the study, which resonated with their lived experience. They felt publicly vindicated. But they were also angered, although not surprised, by Serna’s arrogance. Speaking among themselves, they criticized how he had twisted the Pope’s words about sustainable development to justify the mine. They compared Serna’s declarations to those of a person who enters someone’s house, kills their family members, and then asks for forgiveness and to stay. They wanted the mine to disappear, period. They were unbreakable and were ready to risk their lives to stop the mine. In their minds, little had changed.

This story underscores how public independent investigatiosn directed by a functional public sector can inform debates about development models and help communities harmed by extractive industries. If indeed public investigations have grave limitations and obstacles in Guatemala, part of the struggle is to make it so that studies like these over the socio-environmental impacts strengthen the right to consultation, and the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. For now, these matters appear separated, in the courts, but not for the communities.

Nicholas Copeland is a cultural anthropologist, teaches American Indian Studies and social theory in the Department of Sociology at Virginia Tech, and is part of the Guatemalan Water Network (REDAGUA). He is also the author of The Democracy Development Machine: Neoliberalism, Radical Pessimism, and Authoritarian Populism in Mayan Guatemala (Cornell University Press, 2019). Available open access.