Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aqui.

Elections in Peru are a complex and above all enduring puzzle. On April 11, the country held general elections ahead of the July 28, 2021 bicentennial. The results put Peru en route to a second round between Pedro Castillo, a teacher and rondero from Cajamarca, and Keiko Fujimori, daughter of former dictator Alberto Fujimori.

I begin with a pertinent self-criticism. Many of us noticed Pedro Castillo for the first time between June and September 2017, during the government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, when Castillo led and was a main actor in a protest alongside thousands of teachers, particularly from the country’s interior. At that time, no one could have anticipated or at least given the benefit of the doubt to the efforts to put him forward as a candidate in the elections—much less with the vote percentages he has now attained. We forgot about him.

The main demands of that 2017 protest included calls for an increase in salaries, payment of the social debt, overturning the Public Teaching Career Law (legislation passed by Congress in 2012 that submitted public teachers to an obligatory performance review), and an increase in the education budget. In effect, one of the promises of former President Kuczynski’s campaign was to raise teachers’ salaries at all levels. But the pledge was not fulfilled, neither in the amount nor the time period that had been promised.

The new leader of the rank-and-file teachers movement organized at the national level—under an opposition leadership that challenged the traditional leadership of the Unified Education Workers’ Union of Peru (SUTEP)—was Pedro Castillo, a teacher in the campesino community of Chota, Cajamarca. Opposing the SUTEP leadership, different grassroots groups at the national level began to form the new SUTE-Regional, or SUTER. The formation included leadership representing the country’s interior, as well as horizontal assembly dynamics and the leftist rhetoric of Marxist intellectual José Carlos Mariátegui in its messaging.

We didn’t see Pedro Castillo again until he appeared in presidential debates organized in the capital ahead of the April election. He went almost undetected in the campaign, but then polls began to reflect that Castillo’s support was on the upswing. I am also certain that even part of the leadership of Perú Libre, Castillo’s party, hadn’t conceived of the results he achieved.

On the night of November 15, I wrote a short piece arguing that there are new social actors present in the mass demonstrations that have emerged outside the centrality of the capital and who do not hold a permanent seat in Peru’s formal decision-making processes: there are regional, communal, Indigenous, youth, and local leaders working in their places of origin who will forge a political force that will give a glimpse of representation that goes beyond the current official political cast. These actors don’t receive much attention, but they could, however, end up assuming an important role in the coming years. I am referring to sectors that for decades have voted for social change and then were betrayed and forgotten once politicians got into power—the campesinos, small farmers, workers, rural Andean communities, and youth, among others.

I continued—and continue—to argue that the popular unrest demands changes and not trade-offs among the same political actors that are responsible for provoking an institutional and constitutional breakdown. In November 2020, Manuel Merino, a member of Congress with Acción Popular (AP), led an illegitimate political maneuver to remove then-President Martín Vizcarra from office just eight months before the 2021 elections. Merino became interim president, and a massive popular mobilization forced him to resign five days later. As a result, Peru had three presidents in a single week.

A month later, in December 2020, under a transitional government led by Francisco Sagasti, a member of Congress with the Partido Morado, a massive protest of workers and agricultural laborers erupted and managed to overturn the Agrarian Law, a legacy of Alberto Fujimori’s government. The repeal of the law, which Vizcarra’s government had extended for 10 years, had been a constant demand of agricultural producers who called for substantive improvements in working conditions: salary increases, benefits, bonuses, family allowances, and grants.

Behind the government crisis Peru is experiencing is the construction of a political project for the country that includes everyone and that is being driven by the rightful representatives of that population construction. And responsibility falls on the progressive sectors of the country to rebuild a new social contract based on the ironclad defense of civil rights and the values of justice and equality.

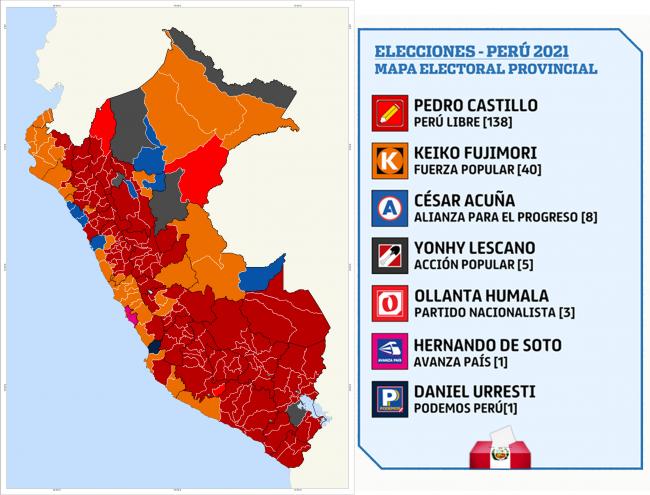

That’s how we find ourselves facing a peculiar political situation that saw a rural school teacher compete alongside—and win—in the first round with George Forsyth, dubbed an outsider; Keiko Fujimori, representing classic Fujimorismo; Hernando de Soto, representing technocratic Fujimorismo; Rafael López Aliaga, representing ultraconservative Fujimorismo; and Yhony Lescano, of Acción Popular. All of these right-wing candidates had greater economic resources, campaign strategists, political and media spokespersons, social media teams, and media presence.

Analyzing the data from the first rounds in 2021 and 2016, marked differences are evident. In 2016, the Left had a chance to make it to the second round. Perú Libre did not participate, but another lefist candidate and party did: Verónika Mendoza of Frente Amplio, a coalition of various left-wing groups and movements that formed in 2010 and split after the 2016 elections. Mendoza won 18.7 percent of the vote in 2016. Now, in 2021, she obtained just 7.8 percent. Frente Amplio’s 20 members in Congress in 2016 were reduced to six in 2021. In contrast, Castillo won 18.5 percent of the vote and his party, Perú Libre, won the largest minority in Congress with 37 seats. Frente Amplio, for its part, did not pass the 5 percent threshold in the congressional election needed to maintain its party registration and lost its electoral status.

What explains these results? In a serious and realistic effort to look for an explanation, we might dare say that Castillo’s initial victory is due to the votes of thousands of teachers, rural campesinos, and Andean migrants situated in socioeconomic classes of low income and poverty, known as Sector D, and extreme poverty, known as Sector E. I do not believe that these sectors have voted out of protest; on the contrary, theirs is a vote of both hope and lament.

It is no surprise that Peru’s mishandling of the pandemic has been among the worst in the world, according to Financial Times reporting that reveals the true impact of Covid-19 on mortality rates. The problems faced by the millions of families who have had to sell their properties to access an ICU bed or to buy oxygen led to the rejection and distrust of candidates who failed to connect with the massive suffering and helplessness within settlements in the capital Lima or forgotten campesino communities.

Similarly, while thousands of children in the school system were expected to attend classes virtually, videos circulated on social media of entire families and teachers walking kilometers to be able to find an internet or radio signal. In short, the pandemic did not affect everyone equally. It has led us to question the much vaunted “Peruvian miracle” rooted in mineral exports as a model of successful development. Years of economic bonanza have not translated into more resources for the health and education sectors, for example. The myth has collapsed.

How would these sectors not identify with Castillo, if they saw him as one of them? Ethnic factions, places of origin, cultural practices, and even language and emotions are at play. Meanwhile, in Lima, we don’t identify with our civilization’s Andean-Amazonian foundations and tend to back proposals that offer to maintain the status quo or make changes without really changing anything.

A poll published on May 2 reported 43 percent support for Castillo and 34 percent for Keiko Fujimori in the second round. Fujimori enjoys the most support from the rich and well-off sectors of the population, such as the socioeconomic groups known as Sector A (81 percent support) and Sector B (45 percent support). A percentage (41 percent) of the middle-income classes in Sector C also intend to vote for her. On the other hand, those of the poor socioeconomic sectors, where the majority of the population is concentrated, plan to vote for Pedro Castillo, such as Sector D (46 percent support) and Sector E (60 percent support). Regarding electoral attitudes, the poll found that 22 percent of Peruvians definitely will vote for Fujimori and 50 percent definitely will not vote for her, while 36 percent will definitely vote for Castillo and 36 percent definitely will not vote for him.

The two electoral options have opened a process of polarization expressed in platforms, political positions, key proposals, and main arguments that not only represent a central ideological confrontation between left and right, but also a political and social face-off between change and continuity. We are still waiting for guarantees that the changes that each candidate offers will respect the gains won in the last 10 years, such as respect for human rights, sexual and reproductive rights, respect and care for Indigenous communities, as well as the maintenance of constitutional, political, and economic stability.

Finally, the political subject in Peru is not Pedro Castillo. The active political subject is a national popular-rural bloc that for decades has voted for social change and that ends up being betrayed and forgotten by those who occupy the seats of power. This bloc has grown and won rights, but it has still not managed to consolidate itself. Those labor, environmental, and gender rights, among others, deserve to be guaranteed. We hope this will come to pass, and we must demand it. Votes are not a blank check.

Today, Peru should lean more toward José María Arguedas—one of the country’s greatest voices of Andean literature—than Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian author living in Spain who has called for a vote for Keiko Fujimori.

Alejandra Dinegro Martínez is a sociologist from the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM), graduated from the Master of Social Policy. She is a columnist and political analyst with experience in public management, as well as the author of books on youth employment and public food programs.