Geraldo arrived at the La 72 migrant shelter in Tenosique, Tabasco, in September. He was applying for asylum in Mexico, and had been transferred there from a detention facility, because he couldn’t legally be held in detention any longer as an asylum seeker. Geraldo was one of the hundreds of migrants and asylum-seekers who I registered into migrant shelters while researching and volunteering in Mexico’s southern border region. Like Geraldo, the vast majority of those people were from Honduras, and most of the rest were from Guatemala and El Salvador.

Geraldo told me that while in detention, he had made one call to his mother, who lives in the U.S. It was the only call he was able to make while in detention, because he had no money for more. Soon after speaking to his mother, Geraldo learned from other people detained in the facility that someone had been calling their families and demanding bribes from them, telling them that if they paid a certain amount of money, their detained loved ones would be released more quickly. Those who had the financial resources to call their families more than once could warn them that this was an extortion attempt, and not to pay the bribe. Since Geraldo wasn’t able to call his mother again, he couldn’t warn her, and so she paid the bribe—for nothing.

Bribes are not uncommon in this part of Mexico, but what is remarkable about this instance is that the person who demanded the bribe from Geraldo’s mother not only had access to her phone number, but was also able to send someone to a money transfer service, and picked up the money in Geraldo’s name, which is legally impossible unless the person picking up the money has the recipient’s ID. This anecdote is just one example of the alarming level of collusion between organized criminal groups and the Mexican security forces and immigration agents who run the detention center where Geraldo was detained, and possibly even agents at the money transfer company. Near Mexico’s border with Guatemala, immigration enforcement, security forces, and organized criminal groups actually share many of the same objectives, and often work together. That is to say, they all profit in overlapping ways from increasing detentions and deportations of undocumented migrants.

Mexico, Guatemala, and the United States have drastically increased immigration enforcement in southern Mexico since 2014, when the southern states of Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Tabasco began implementation of the Southern Border Plan (SBP), which aimed to deter migrants and would-be asylum seekers from reaching the U.S.-Mexico border. The United States’ massive financial support to Mexico in their efforts to increase immigration enforcement has been written about extensively in NACLA and other outlets. This piece focuses on what has changed on the ground since 2014 and throughout Trump’s first year in office, as experienced in migrant shelters in Ixtepec, Oaxaca, and Tenosique, Tabasco.

Since the passage of the SBP in 2014, the southern border zone has been the site of a massive and unprecedented increase in border and immigration enforcement activity that has made passage through the border states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, and Quintana Roo much more difficult and dangerous. From the U.S. government’s perspective, the child migrant crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border during the summer of 2014 increased the urgency of stopping Central America migrants before they could reach the United States. Since at least 2011, U.S. funds have been directed toward fortifying Mexico’s southern border through the Mérida Initiative, a U.S.-Mexico security cooperation agreement, which includes border and immigration enforcement provisions. The consequences of the SBP have been wide reaching, particularly in increasing the vulnerabilities migrants and asylum-seekers face on their journeys. A huge portion of the migrants I interviewed who made it to the shelters had been assaulted, extorted, robbed, or all three, as they have been forced to embark on less-traveled, more dangerous migration trails in regions often controlled by organized crime. Many were injured fleeing from immigration agents, and/or assaulted and extorted by organized crime who led them astray them as they attempted to circumnavigate immigration and military checkpoints by taking back roads and mountain paths rather than well-established routes.

Impacts of the Southern Border Plan

The official, stated objectives of the SBP are to facilitate orderly migration in the southern border zone of Mexico, and to protect the human rights of migrants. Unsurprisingly, however, the SBP has had the opposite effects, and human rights defenders in the region argue that the official goals of the program were never its actual objectives. According to Salva LaCruz, of the Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center in Tapachula, Chiapas, the SBP has two central objectives: to increase the number of Central American migrants detained in and deported from Mexico, and to concentrate the detention of migrants in the southern border zone rather than further north. Operationally, that means that immigration enforcement efforts under the rubric of the SBP are designed to make it more difficult for people migrating or seeking asylum to reach migrant shelters and humanitarian aid.

In addition, the SBP facilitates increased coordination among Mexico’s Navy, the Federal Police, state and municipal police, the Army, and the National Immigration Institute (INM) and neighboring countries. Security forces have received access to improved technology, personnel, and training. The result of these efforts has been skyrocketing numbers of detentions and deportations.

In 2013, Mexico detained and deported 80,079 people; in 2016 that number had increased to 159,872. Currently, detentions and deportations continue at a rate approximately proportional to the 2016 rate, but migration itself has decreased by about half. Immigrant rights defenders I spoke with attributed the decrease in migration largely to the rhetoric of the Trump administration, and increased detention and deportation to the SBP.

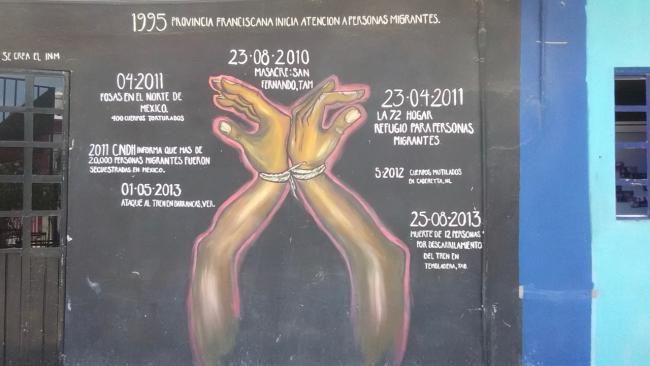

According to Ramón Marquéz, director of the La 72 migrant shelter in Tenosique, Tabasco, the first enforcement operations deployed under the rubric of the SBP were a series of raids on “the Beast,” the famous cargo train that was the principal mode of transportation for migrants crossing Mexico until 2014.

Rita Marcela Roble Benítez, also of the Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center, told me that starting in 2014 the speed of the train was increased, and metal bars added to of it in order to make it more difficult and dangerous to climb aboard while in transit. Benítez also said that under the SBP, it has become common practice for immigration enforcement operations to be carried out near migrant shelters, previously a rare occurrence. As a result of such enforcement operations, migrants can no longer ride the train into towns like Ixtepec, Oaxaca, where the Hermanos en Camino (Brothers in Transit) shelter is located. Instead, they are forced to jump off before reaching Ixtepec, and find other ways to reach the shelter or continue their journey.

A major effect of the increase in enforcement operations on the train is that migrants are forced to walk along back roads, through fields and over mountains. Whereas before 2014 the majority of crimes against migrants were committed by organized criminal groups on the train, now a huge portion of migrants are being attacked and robbed by petty thieves as they try to find their way through the countryside. In 2014, human rights activists opened a new shelter in Chahuites, Oaxaca, which they operated until this past summer. When I was at Hermanos en Camino in August 2017, however, volunteers were cleaning up what remained of the shelter in Chahuites, which had been forced to close by the mayor. He had made closing the shelter a priority of his 2016 election campaign, blaming migrants staying at the shelter for crime in the community.

In 2014, the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) conducted an investigation in the southern border zone to understand the initial effects of the SBP, and discovered a significant increase in facilities and technology deployed in immigration enforcement in the southern border zone. WOLA noted that the INM was installing new biometric data collection technology provided through the program.

During my time in Chiapas in early September 2017, I was detained for a night in the Siglo XXI (21st Century) INM detention facility in Tapachula, the largest immigrant detention center in Latin America. I was processed for detention along with hundreds of Central Americans, where we had our pictures taken on impressive-looking cameras and our fingerprints collected. I wound up at Siglo XXI after being detained at a temporary moving checkpoint outside of Huehuetan because I had forgotten to carry my passport that day. During the time we were held in the small facility by the side of the highway, INM agents detained a local Mexican man who was on his way home for work for a few hours and interrogated him about where he was from, because he wasn’t carrying an identification card. Two men from Honduras and one of their sons were detained in the same facility with me that day, and when we were bused to Siglo XXI detention facility at the end of the day, INM agents put a woman they had detained separately on the bus too.

According to Salva LaCruz of the Fray Matías de Córdova Center for Human Rights, U.S. personnel are consistently involved in training Mexican immigration agents in the detention centers. In addition to new detention facilities operated by the INM, LaCruz told me that the SBP has facilitated the construction of several new facilities under the direction of Mexico's Navy. These facilities are located well within Mexican territory in the border states, through which highway traffic is routed for customs and immigration inspection, coordinated by the INM.

Coordination among security forces facilitated and funded by the SBP is organized by Municipal Security Committees in towns on the border and along major migrant routes. These committees facilitate communication and joint operations between the INM, whose agents are legally prohibited from bearing arms, and security forces. As a result, many immigration enforcement operations carried out by the INM are now accompanied by armed agents. Additionally, police forces have been carrying out their own immigration enforcement operations, in direct contravention of the Law of Migration, which prohibits any agencies other than the INM from enforcing immigration law except at the request of the INM.

In our interview in late August of 2017, LaCruz described to me how just the week before, the Chiapas state police had set up checkpoints in the center of Tapachula and various neighborhoods and detained all the foreigners they encountered, even people who were already in asylum proceedings. According to LaCruz, such illegal immigration enforcement operations happen frequently. Benítez told me that in other parts of the country, immigration raids are also being carried out by private security hired by the state. At La 72, the director of the legal clinic for refugees told me that she believes that the INM is detaining people who are in asylum proceedings, and therefore not legally supposed to be detained, as a way of threatening the shelter and its efforts.

Finally, there are the mobile enforcement operations carried out by the INM. These operations take two different forms, which several people resting in the migrant shelters described to me in interviews and informal conversations. The first of these operations are what people refer to as volantes, or temporary checkpoints that INM personnel establish along roads. Many migrants described encountering volantes while walking, and being chased into the mountains by immigration agents, sometimes with dogs. One person told me he had escaped several such situations while crossing Chiapas on foot, in addition to avoiding the INM inspection stations on the highways.

The other type of mobile enforcement operation the INM uses is simply driving along the major roads leading to the border in a van, and attempting to capture anyone they suspect is an undocumented migrant along the way. A migrant I interviewed at La 72 told me that he has traveled that route so many times that he knows what times of day the INM vans make their trips, and is able to avoid them by hiding out along the roadway during those times.

Clandestinity, Vulnerability, and Asylum

If the principal effect of the SBP has been to increase enforcement activities in the southern border zone, the corresponding result of that strategy has been forcing migrants into increased clandestinity. Clandestinity takes a variety of forms, including traveling at night and seeking out less-known routes. In the Guatemalan border town of Tecún Umán, for example, a taxi driver I spoke with told me that until a few years ago, the town was visibly full of people migrating north, but after a series of enforcement actions by the National Police, migrants stay hidden during the day and cross the river at night. Most of the people who arrived at La 72 while I was volunteering there arrived in the morning, after having walked most of the night, though some did still arrive during the day. Many, especially those who had traveled at night, were assaulted and/or robbed along the route, often at the same locations, which volunteers noted during registration interviews.

The team at La 72 described to the new volunteers how in the past they have denounced crimes against migrants to the local authorities, including exact names of perpetrators and locations where assaults and robberies were regularly taking place. They later found out that those same authorities were themselves involved in migrant kidnapping and smuggling rings.

To avoid immigration enforcement and security personnel, people are increasingly attempting to migrate along the longest northward route, through the states along the Pacific coast, in order to evade the zones where immigration enforcement is heaviest. On that route there are currently no migrant shelters, and it passes through the states of Guerrero, Nayarit, and Michoacán, which are experiencing some of the worst cartel violence in the country, and where it is rumored that drug trafficking organizations are forcing migrants to transport drugs in exchange for safe passage. In Michoacán, I saw many migrants along the highway, and a local friend been involved in helping a group Honduran migrants finish their journey told me that seeing migrants there is a new phenomenon.

Displaced and migrating Central Americans are responding to increased immigration enforcement in the southern border zone and the Trump administration’s fear tactics by applying for asylum and humanitarian visas in Mexico. Since 2014, Mexico has seen a rapid increase in refugee and visa applications from Central Americans. The shelters, which in previous years experienced a much larger number of people passing through, are now finding themselves housing people for many months as they wait for their documents to be processed, rather than just a few nights as they gather their strength and wait to jump on “the Beast.” According to a report released by WOLA, just 2,137 people requested protection in Mexico in 2014, and only 25% received it. By 2016, three times as many had applied and 37% had received asylum or complementary protection, in addition to another 3,632, who received one-year humanitarian visas. In 2017, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees predicted that Mexico would receive up to 20,000 asylum requests.

By law, asylum processes are supposed to take forty-five business days to complete, but many are being delayed. Some people I spoke to who were in asylum proceedings had been living at La 72 for a year or more, waiting for a response. Others had been denied asylum and were appealing the decision. Of the approximately 700 asylum cases that the legal team at La 72 accompanied in 2016, only about 22% were accepted. The rate of acceptance and interview process are the same for unaccompanied minors as for adults, though the acceptance rate is slightly higher for women traveling with children.

In addition, an increasing number of families, unaccompanied minors, LGBTQ people, and women are seeking refuge from the repression, violence, poverty, and displacement that is ravaging the Northern Triangle of Central America. Whereas in previous years the vast majority of people who stayed in the shelter were headed to the U.S., now close to fifty percent are simply looking for a safe place to live, and hope to stay in Mexico.

Sister Diana, who is in charge of asylum proceedings at La 72, told me that the legal team there understands the delaying of asylum proceedings as a strategy of the Mexican state to force people to abandon their processes, so that the government can report a high acceptance rate while effectively preventing many people from gaining asylum. Sister Diana told me that around 90% of asylum proceedings are extended, and because of that, 45% of applicants are abandoning the process because they need to find work or travel further to flee organized crime. According to Sister Diana, although documentation of this is exceedingly difficult to find, it is understood among refugee advocates that the United States pays Mexico by the head for deportations of Central Americans. The situation in Mexico’s southern border zone is an enormous humanitarian emergency, caused almost entirely by the United States government and its state and elite partners in Mexico and Central America. It appears on track to only get worse, despite denunciations by civil society.

This past spring,

U.S. Southern Command announced the creation of a joint task force for the southern border, to include land and air patrols and reconnaissance, with support from the U.S. Southern Command, a project that could include a base in El Petén, Guatemala, where the Guatemalan military and national police forcibly displaced

around 700 people from the municipality of La Libertad on June 2, forcing them to migrate to the border of Campeche, Mexico. Voces Mesoamericanas and the Mesa Transfronteriza argue rightly that these developments portend a deepening of U.S. intervention in and militarization of the region, which will only lead to more suffering for local communities and the migrant population.

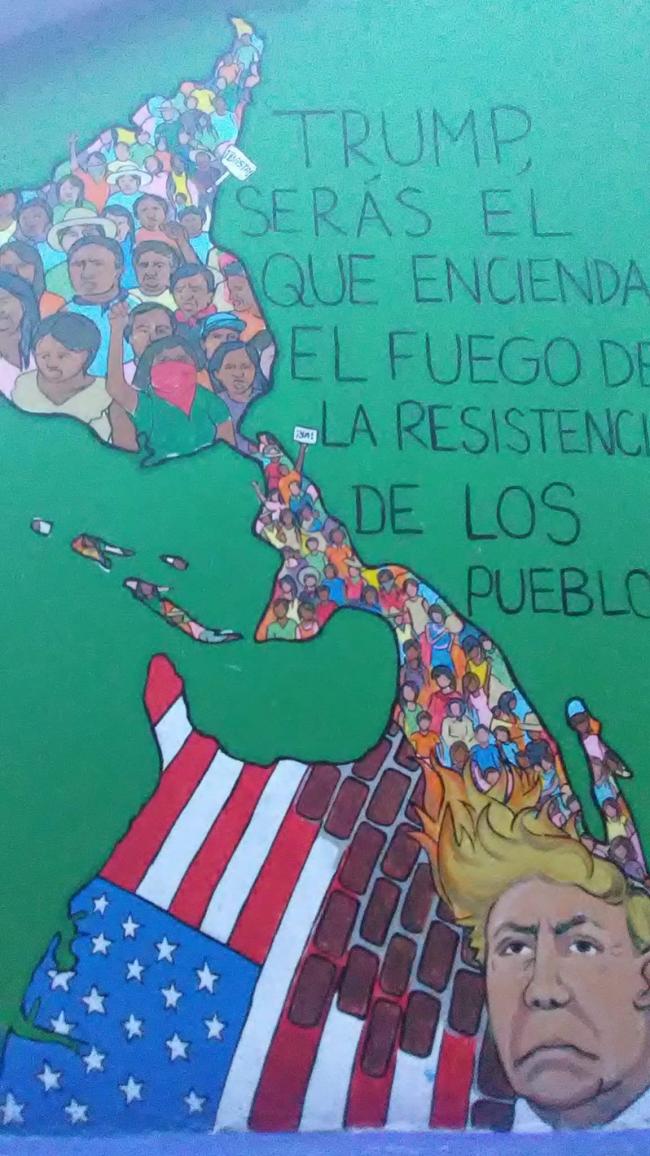

Ramón Marquéz, director of La 72, describes the politics of migration in the southern border region as a war. He says it is a question of “territorial control, through terror, through persecution: it’s silencing the people. Not just the people in transit, but also the local population. This is a dynamic that extends throughout Central America. The Southern Border Program is just one small part of a strategy to control all the natural resources, all the economic resources of the region.”

Nicholas Greven is finishing his Master’s in Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington. He lives in Indianapolis and organizes with IDOC Watch, the Bloomington Solidarity Network, UndocuHoosiers Bloomington, and the No New Jail Coalition.