This article was originally published in Spanish and English by Ojala.mx on January 24, 2025. Find the original article here.

During his first week in office, Donald Trump pushed forward his aim of remaking the US government in his image at breakneck speed. On inauguration day he signed 46 proclamations, memoranda and executive orders that threaten human and non-human life and enshrine ultraconservative, racist and anti-trans restrictions that explicitly target the most vulnerable members of society and threaten to upend the lives of millions.

These presidential actions advance militarism domestically on the pretext of controlling migration and narcotics along the southern border. On Wednesday, the US Department of Defense announced 1,500 additional active duty troops would be sent to the border, and there’s likely to be many more such deployments.

Since at least 1989, soldiers have participated in domestic counternarcotics operations—and more recently in policing migration—through Joint Task Force 6 (now named Joint Task Force North), which is headquartered at a military base in El Paso, Texas. The scaling up of this mission, with soldiers flooding the southern border to “fight” drugs and control migration, potentially in a policing role, could signal the expansion of what I’ve called drug war capitalism.

Using the army to control migration and drugs, especially over an extended period of time, may end up becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: it could dramatically increase the violence Republicans (falsely) portray as already rampant at the south border. This would have disastrous impacts on communities in cities, towns and reservations in the border region. The impacts of militarization are already clear to many border residents on the US side, whose friends and family continue to be exposed to extreme violence across the border in cities like Matamoros, Reynosa, Nuevo Laredo, Ciudad Juárez, and Tijuana.

Republicans have portrayed Mexico as a country under criminal control. For decades, the “solution” on the part of Republicans and Democrats in Washington has been more militarization, which has torn social fabric and fueled previously unknown levels of violence in different parts of the country.

It’s my hope that reflecting on how militarizing the control of narcotics and migration has propelled—rather than stopped—war south of the border can provide insight into the potential consequences of large scale troop deployments in the southern US.

Militarization on Tap

One of four proclamations Trump signed on January 20 classifies border crossing by undocumented migrants from México into the US as an “invasion,” and calls on the Secretaries of State and Homeland Security (DHS), as well as the Attorney General’s office (AG), to “repel, repatriate, or remove” migrants. This decree enshrines racist tropes of migrants as carriers of disease, and as a threat to public safety and to national security in law.

Another declares a national emergency on the US border with Mexico. “Our southern border is overrun by cartels, criminal gangs, known terrorists, human traffickers, smugglers, unvetted military-age males from foreign adversaries, and illicit narcotics that harm Americans, including America,” reads the proclamation declaring a national emergency. This wording is important because it so clearly illustrates the conflation of undocumented migrants with terrorists, traffickers, potential insurgents and narcotics, which is required in order to demonize, stoke hatred toward and further criminalize entire communities. The proclamation gives DHS and the Department of Defense 90 days to decide to invoke the 1807 Insurrection Act along the southern border, which would allow the President to deploy the army or national guard to carry out policing duties.

Of the 26 executive orders signed Monday, one directs the DHS and—significantly—the Department of Defense to participate in building border barriers and walls as well as to “take all appropriate and lawful action to deploy sufficient personnel along the southern border of the United States to ensure complete operational control.” Another directs the US Northern Command to come up with a plan to “seal” the south border against migrants and narcotics within ten days. A memorandum calling for a hiring freeze for federal workers does not apply to the armed forces, DHS, or police.

The View from México

If the Mexican experience teaches us anything it's that when troops are deployed to enforce prohibition—particularly if their presence is established over an extended period of time—the outcomes include killings, disappearances, and forced displacement.

In Mexico, the militarization of prohibition has fuelled increasingly extreme violence over the last two decades. The strategy of using soldiers—which, it should be noted, are armed and trained by the US—in a policing role to control narcotics has led México down a path of profound human suffering, with over half a million direct victims of homicide and disappearance and hundreds of thousands displaced since December, 2006.

Let’s get something straight right off the top: cartels are not autonomous groups of mafia baddies. Rather, they’re non-state armed actors, or paramilitary groups, whose role in moving narcotics is articulated and regulated—sometimes by force—by the army and the marines. Cartels are an outcome of militarized prohibition, not something it can destroy.

The story goes way back, but over the last quarter century México received record support from the United States to beef up its war against cartels. This took place in large part under the Mérida Initiative, a security and weapons transfer program worth billions of dollars that ran from 2007 until 2021.

But the flow of narcotics didn’t taper off. What happened instead is that the army outsourced the work of narcotics trafficking to cartels in return for two things: protection money payoffs and cooperation in carrying out repression.

Soldiers as Migration Police

Over the past five years in Mexico we’ve begun to understand more concretely how the army’s involvement in policing migration creates conditions of increased danger and exposure to death for migrants transiting through México. It also curtails mobility for Mexicans more generally, and specifically impacting Black and Indigenous Mexicans who tend to be profiled, searched and detained at higher rates.

Months after he became President in December, 2018, and in the context of pressure from Trump, Andrés Manuel López Obrador agreed to an “enforcement surge” that saw the mass deployment of the National Guard against non-Mexican migrants transiting northward.

In May of 2019, the Mexican senate approved the National Public Security Strategy, which conflated “uncontrolled migratory flows” with other “risks and threats” to national security including organized crime, climate change, the collapse of critical infrastructure and otherwise. The first test of using soldiers in migrant detention took place from June 10 to 30 2019, just three days after a migration control agreement was reached between the Trump and López Obrador administrations following Trump’s initial tariff threat.

According to México’s Secretary of National Defense (DEFENSA), it began policing migration because of migrant caravans in 2019. DEFENSA points to the role of activists and the use of the court system as leading to the “overwhelming” of civilian migration control. This reading of migrant caravans ascribes malicious intent to participants, rather than understanding caravans as a desire to create collective safety. At the same time it strips organized migrants of agency by asserting they are controlled or manipulated by activists.

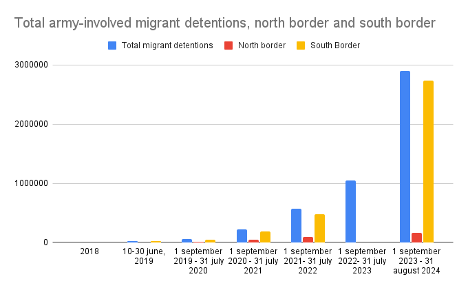

Statistics kept by DEFENSA show a rapid escalation in their role policing migration over the past six years (prior to 2018, the Army did not publish statistics on migrant detention). The army said last year it was involved in over five million migrant “rescues” during López Obrador’s six year term. In Mexico, “rescue” is a euphemism used to describe migrant detention.

It’s not a coincidence that the role of organized crime in the movement of migrants in México has undergone a profound transformation since 2019. The increased use of the military to police migration, and the militarization of the National Migration Institute, have created new opportunities for criminal groups to participate in the transit of migrants from north to south.

It is crucial to avoid parroting official discourse, which suggests cartels control the flow of narcotics and migrants, or that state forces are overwhelmed, either by migrant caravans or by criminal actors.

The role of non-state armed groups in organizing the transport of narcotics and‚ increasingly, undocumented migrants, is overseen and coordinated by the armed forces. As mentioned above, this is a direct and known outcome of the militarization of prohibition, and which can be extended to the prohibition of free movement on the part of undocumented people from the global south.

Consequences and Possibilities

López Obrador’s successor Claudia Sheinbaum has created the appearance of challenging Trump on migration policy. She’s said for example that “we do not agree that migrants be treated as criminals,” but her administration and the one that preceded it have done just that. Sheinbaum has enthusiastically continued the legacy of militarization left by AMLO, at the same time her political leeway is constrained by US power.

The most tragic example of the criminalization of migrants in recent memory is the 2023 fire at a migrant prison in Ciudad Juárez that killed 40 men who were in detention for being non-status migrants, and injured dozens of others.

Two days after Sheinbaum was inaugurated on October 1, 2024, the Mexican army shot and killed six migrants in Chiapas, wounding dozens; just over a month later a second similar incident occurred in which the National Guard killed two migrants and injured four by gunshot in Baja California Sur.

The militarization of prohibition and migration in Mexico have generated tragic consequences for the wellbeing of the population at large. Over the years we’ve learned that this kind of militarization occurs in tandem with paramilitarization (the proliferation of cartels), hampering the ability of local groups and communities to organize in defense of their territory, neighborhood, or otherwise.

In this context, anti-militarism has increasingly become a central tenet of México’s massive feminist movement, and is a cause increasingly taken up with vigor by grassroots organizers and civil society groups. But migrants rights groups in México have struggled to position the issue in a meaningful way, and as a non-voting constituency, migrants are treated as expendable —or as bargaining chips to make deals with the US— by Mexican political parties.

I expect to be writing more about the impacts of Trump’s administration in coming months and years. For now, I want to focus on a single element of what’s been proposed as part of the Trump 2.0 shitshow: sending the army to seal the US side of the southern border is a fool’s mission. Of course trafficking will still take place. But how it takes place is likely to become even more violent.

Sadly, it’s a myth that this kind of violence is something those in power wish to avoid. In Mexico we’ve seen how the militarization of prohibition leads to the strengthening of paramilitary organizations, as well as increased stigmatization and criminalization of victims. This crescendo of state and non-state attacks on poor and working people can demobilize and silence even the most powerful forms of popular resistance.

In this difficult context, one thing is clear: there’s never been a better time for cross issue, international organizing against militarization, the tyranny of borders and the prohibition of narcotics.

Dawn Marie Paley is an investigative journalist and author of Drug War Capitalism and Guerra Neoliberal. She is the editor of Ojala.mx and a member of NACLA’s Editorial Committee.