Leer este artículo en español.

Five decades after the coup d'état that changed social and political life in Chile, Patricio Guzmán (1941), a filmmaker whose works have recorded the nation's most defining milestones, points out that "Chile has a heavy past that remains latent." He defines the country as a territory "surrounded by memories that prevent it from moving forward, like a kind of past that weighs and does not pass."

His comment is not by chance. In addition to documenting the country’s convulsive history, Guzmán has, alongside other artists, contributed to shaping, circulating, and transmitting the cultural memory of the dramatic events that Chile commemorates this September 11. He was recently awarded the 2023 National Prize for the Performing and Audiovisual Arts for this work.

In this conversation, Guzmán, who lives in France, reflects on the current moment in Chile and ways of engaging with the past. We spoke on Zoom on August 24, 2023. Our conversation has been translated from Spanish and lightly edited.

Manuela Badilla: How do you see Chile and its people on this occasion of the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the coup d'état?

Patricio Guzmán: I don't know how the Allende government echoes in Santiago today. I knew two or three years ago, because things happened in Chile that caught everyone's attention. Thousands of people demonstrating was a strange signal that the country had memory. And that large demonstration was not organized by political parties or by any institution. It was like magic, a strange thing of the internet and coordination to be able to reach such an enormous number of people. This continued for a month.

I recorded part of that process and with that I made my last film, My Imaginary Country, and I was happy. But little by little, as time went by, you began to realize that it’s not so easy, that the pueblo for a long time has been led and influenced by people that have nothing to do with Allende. Then things began to deflate.

MB: And why do you think that is the course things took?

PG: I think that, as there was no party structure, the social manifestation was almost completely annulled. There is a possibility that it could be repeated, but not for a long time. In other words, once again we are facing interminable periods of time, like after the coup d'état. We feel like nothing is happening, like the country continues to experience the inertia of time, and this wins over the enthusiasm of some. Ultimately, we are now waiting once again for something to happen, as we have been for a long time.

I have lived through all this, as surely you and many other people have, with a mixture of enthusiasm, skepticism, and patience, because you have to be patient for the real moment to arrive. What is clear is that the country is not happy. There is a current against what is happening, it is enormous, millions of people who do not share the life we have been forced to live. And this is going to continue because I do not think the government will make any real adjustment. It is a period of impasse, and I find it very interesting. I love it, because that's the kind of thing I make films about.

MB: Lately, we have seen the emergence in the public sphere of a memory that, up until now, had remained more underground: the memory of the Right that supported the coup, and in the more extreme cases of the Right that continues to justify the crimes of the dictatorship. What do you make of the emergence of this conservative memory?

PG: It is a pity that this is happening. It is bad news for democracy. I believe that the mood of a certain right wing is one of rage, of indignation, of restoring a history that they believe was not so, of restoring their role against the "chaos" of the Popular Unity [government of Allende], of doing something against the contradictions that Allende held.

In short, there is resentment, a wound that is not closed. I thought that this was only the case on the left, but it is from both sides. And that places everyone in a certain state of disorientation, in a certain past that does not pass, in a heavy past that continues to be latent instead of being— half a century later—overcome.

But as long as the coup d'état continues to serve as the axis of memory, just as much for one side as the other, the country will remain in tension. It is dramatic that Pinochet is still present in a country that has been under a democratic regime for decades, but that has not yet erased the figure of Pinochet, nor the dictatorship. I am very sorry for that.

MB: How do you explain the persistence of this figure of the dictator for all these years? What needs to happen in this country so that we can, at least on that level, leave him aside?

PG: Politics must continue to advance as much as possible, and the future political system must instruct many middle classes that do not know what to do or are indifferent. There is no other way. I do not think that it is any different in Peru, Ecuador, or Venezuela: the whole continent is entangled in tremendous fascism, with debts that are not paid, with corruption that is multiplying.

Latin America is in the worst place on Earth today. Elsewhere there is civil war, there are fierce conflicts, but at least these have been defined: if there is war, well, let there be war, but at least it is declared. In Chile, on the other hand, everything is hidden, everything comes from under the table. Journalism is supposed to be very serious, and the University of Chile is supposed to be serious, and so is the Catholic University, but there is a kind of distrust in these institutions, because they do not move, they don’t agitate, they have remained stagnant. So, we are more alone than ever.

MB: In your latest film, My Imaginary Country (2022), the youth of Chile are protagonists, especially young women. How do you see the youth of Chile today, who have been at different times in our history the focus of your cinematography?

PG: Chile is a country surrounded by memories that prevent it from moving forward, a kind of past that weighs and does not pass, a past that has not been clarified and continues to surround us. And this is greatly influenced by public opinion, the attitude of the university, of the students. So there is a feeling of stagnation, that everything has come to a standstill. And in the meantime, what will become of us. We are alive and fighting for the situation to change, but nobody gives us a chance.

MB: The young women who were the protagonists of My Imaginary Country are now living through a different moment, of little energy, of uneasiness. How do you perceive them in this new post-social uprising, more conservative scenario, facing the advance of the ultra-right not only in Chile, but also in Latin America?

PG: I think we have to wait patiently for a freer space to come and for the people to reintroduce themselves in a movement that we don’t know yet how it will be. We don't know if it will happen this year or in 20 years.

If I were to make a film tomorrow, it would be a film of questions: Why do you think this is happening? Why did you stay locked up instead of going out to the demonstration? Why don't you trust anyone? Who is the one who has hurt you the most? I would question people to see what conclusion they come to. I have no idea what would come out of it, but it's exciting to do it that way. A film that interrogates is needed now, here. The film would be called "The End." Because it is the last frame of something that we lived through, but there is no proposal for new titles and new plot. It is very complicated.

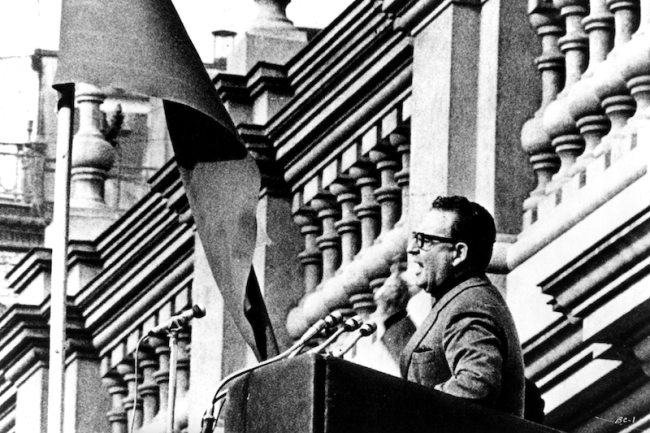

MB: In your film Salvador Allende (2004), you confess: "I would not be who I am if Allende had not embodied that utopia." This September 11, the 50th anniversary of Allende's death, how do you see this historical figure, and do you think he has had the recognition or the place he deserves in Chile?

PG: I don't think so, because Allende is a revolutionary and what came afterwards was the most right-wing government the country has ever had. For many Allende is only looked upon with respect out of good manners, but they hate him, they detest him. And sometimes they do not even take notice, they ignore his Popular Unity party.

I think Allende is a national figure that will continue to grow, and it is a positive myth for us, because before him we did not have such a broad leader. The generation of politicians that has come after him is very interesting. I like them, and I am enthusiastic about them, but it is not the same as it was before. There is a kind of rupture in the structure of Chile as a country, as a nation, as a state.

MB: After the coup, you left Chile and never came back to live in this country. However, much of your work and reflections have to do with the things that have been happening here. These commemorations of 50 years since the coup also mark 50 years of your work. How is your relationship with Chile five decades after leaving?

PG: It is very simple. Before Allende I spent five and a half years in Madrid where I graduated as a film director. When Allende was elected, my wife and I said, "We have to go back." It was the most logical thing to do. In the meantime, during my stay in Spain, I was becoming politicized. It was a time in Spain when people were reacting against the dictator and murderer Franco. There were strikes in the universities, unions, transport sector—everywhere. That was the moment when I truly became politicized.

In 1971, I returned to Santiago, and a week later I went to the School of Communications at the Catholic University and asked for films. I told them: what is happening is so extraordinary, so unprecedented, so different, that we have to film. So I proposed to them to make The First Year (1972), a film with images of the first year of the Popular Unity government, which will be released next month in Chile for the first time. We did a restoration as if the film had been made yesterday.

To see the film with perfect sound and impeccable images is very interesting. It is a vision of the Popular Unity in pure joy, because there was no opposition, the right wing went quiet for a year after Allende assumed the presidency. There was, therefore, an enthusiasm without backlash: the entire left parading around Santiago, and not only in Santiago, all over Chile. After making that film, the logical thing was to make The Battle of Chile. And since then I never questioned whether it was right or wrong, if it was appropriate, because it seemed to me the most logical thing to continue making films.

It doesn't bore me to make films about Chile. On the contrary, I'm passionate about it, and I wouldn't make films about any other country.

Manuela Badilla received her PhD (2019) and MA (2013) in Sociology from The New School for Social Research. She is currently an assistant professor at the School of Psychology at the Catholic University of Chile and a researcher at the Center for the Study of Conflict and Social Cohesion.