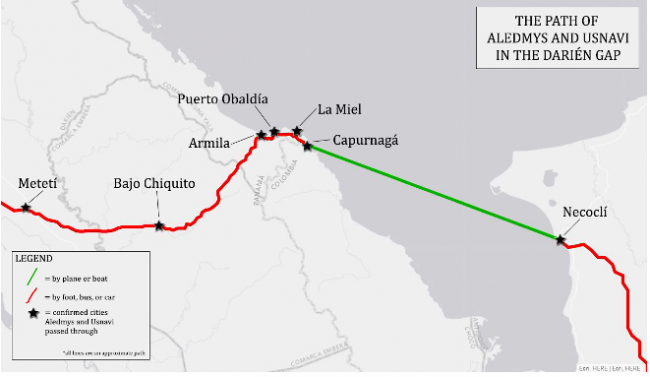

With just a backpack, a small bag, shorts, a pullover, and a pair of shoes, Aledmys and Usnavi began walking through the jungle. They trudged for hours with around 30 other migrants from around the world. At night, they used their backpacks as pillows and drank water from the river that ran alongside. They were heading to Puerto Obaldía, an Indigenous town within the Darién Gap, which connects South and Central America.

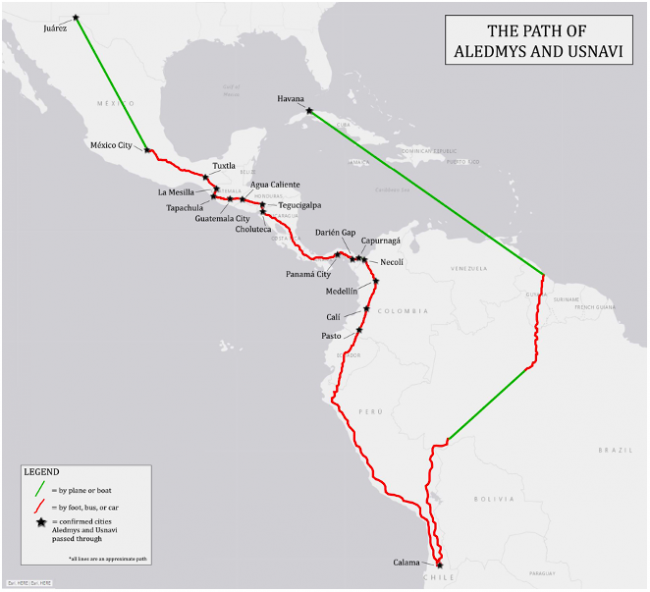

Months later, they arrived in Mexico in the summer of 2019, after leaving Cuba and travelling through 12 countries with the end goal of reaching the United States. There, sitting in a rented house in Ciudad Juárez, Aledmys and Usnavi (whose names have been changed) told us their story as part of a project entitled “Explaining the causes of U.S.-bound migration in an era of migrant caravans.”

When asked why they persisted in the face of so many difficulties, Usnavi responded that it was not bravery that kept them going, but rather survival.

“You do it or you die,” he said, expressing how many undocumented migrants and refugees feel when forced to leave their home countries—escaping from hunger, war, or authoritarianism—in search of a better life.

Braving the Darien Gap

The most perilous portion of Aledmys and Usnavi’s journey occurred in Panamá, in a section of jungle known as the Darién Gap. Migration officials told the pair that their only option was to travel through this region, but warned them, saying, “There are dangerous animals. There are drug traffickers who can kill you. Good luck.”

Thousands of migrants travel through the Darién Gap every year, spending days walking without any clear path. It consists of 66 miles of no roads, slippery terrain due to intense rain, many mountains, and, like the officials said, wild animals and drug traffickers. But the migrants who pass through this dangerous area are fleeing things they deem more dangerous than the jungle: poverty, violence, and political persecution. They come from many countries, including Haiti, Cuba, Cameroon, Congo, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. Between January and mid-April of 2019, the year Aledmys and Usnavi travelled through the Darién Gap, it was reported that 7,316 migrants passed through this region. Many are robbed, sexually assaulted, and face extreme physical hardship on their journey. The towns within the Darién Gap, instead of being places of refuge, are often overwhelmed with the influx of migrants and lack the resources to support them.

When Aledmys and Usnavi reached a hill at the border of Colombia and Panamá, the smuggler they had hired assured them that if they continued straight for two hours they would arrive at their destination. The smuggler did not accompany the group, and unbeknownst to Aledmys or Usnavi, was not leading them in the right direction.

“Smugglers lie all the time,” Usnavi recalled bitterly. At the bottom of the hill, they realized they had not arrived in Puerto Obaldía, as they expected, but rather La Miel, a Panamanian city only about one or two miles from their original starting point. To make matters worse, the Panamanian National Border Service, SENAFRONT, found the group of migrants and told them that they would be deported back to Colombia. The men were crushed, and they cried.

High Hopes and Uncertain Outcomes

SENAFRONT is a common character in the stories of migrants and refugees in this region. Created in 2008, this collection of law enforcement agencies in Panama monitors land and sea borders to prevent trafficking and guerilla violence. They have a large presence in the Darién Gap and have increasingly detained migrants since their creation, enforcing not just Panamanian policies but also the stricter U.S. immigration policies. The United States not only provides training to SENAFRONT, but also millions of dollars a year, especially directed towards security in the Darién Gap.

The second time that Aledmys and Usnavi returned to the jungle, they spent three days there. They met all types of people with wildly different stories, but the reasons for migrating were generally the same: to find better opportunities in a very unequal world.

“We are all in search of the American dream,” Aledmys said. After the two men learned that their new coyote had tricked them, they decided to take off on their own. When asked why they persisted instead of turning back, Aldemys replied, “No one goes back. I prefer to spend my days in the jungle than to return to Cuba.….I prefer to die.”

The pair was just a few kilometers from Puerto Obaldía, where they hoped to find transportation and salvoconductos, or safe passage permits, to continue their journey, when they were prevented from entering the city by SENAFRONT. Aledmys and Usnavi were forced to continue traveling through the jungle without a guide alongside Angolan women, Congolese mothers with newborns, and dozens of other migrants and refugees. The most difficult moment of the journey was when they were forced to leave one Angolan woman and her son behind. The woman was exhausted and injured and begged them to take her son since she could not continue walking. But taking the boy was too much responsibility for Aledmys and Usnavi, who “ were so tired and afraid,” walking for twelve hours a day and hunting for animals in the forest.

“At one point we had only one cookie, but soon we found a frog and we ate it,” Aledmys said. “We were so hungry, so it tasted delicious, and luckily we were not poisoned. We know some species of frogs can be venomous.”

After traveling for days, Aledmys and Usnavi finally arrived in Bajo Chiquito. Bajo Chiquito, unlike other towns in the Darién Gap, is a place where migrants can officially register with the police. When they arrived, SENAFRONT was managing requests from hundreds of immigrants to get their salvoconductos in Panama City. Although the town only has about 300 permanent residents, more than 7,300 migrants arrived in Bajo Chiquito between January and mid April 2019.

After receiving their salvoconductos, the men traveled through four more countries before reaching the Mexican border city of Ciudad Juárez where they told their stories. However, in this city, their plans to reach the United States were complicated by the Trump administration’s strict immigration policies. Under Trump, policies like metering and the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) were implemented. These policies force migrants to wait for weeks—or even months— for their “credible fear” interviews to justify their asylum cases. Due to Covid-19, the U.S. government, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), largely suspended the right to seek asylum on March 21, 2020. This decision, known as “Title 42,” was based on an interpretation of the 1944 Public Health Service Act, and was designed to prevent the introduction of communicable disease into the United States, but it also prevented many refugees from entering the country.

After a while, we lost touch with Usnavi and Aledmys. As far as we know, one of the men is still waiting in Mexico for his asylum case to be processed. The other, who, according to a mutual acquaintance, is believed to be in the United States, must have entered illegally considering the Covid-19 restrictions and Title 42.

Although this is the story of two Cuban men, thousands have had similar experiences. The situation at the U.S. border in recent weeks with the mass deportation of Haitians, many of whom lived in South American countries before journeying north, has brought renewed attention to the Darién gap. Trips through the Darién gap are reportedly increasing, and so are deaths, with 50 this year. Assaults by armed groups and rapes are quite frequent in this segment of a perilous journey. The Darien Gap is a key segment of the very perilous journey that many other migrants and refugees from Latin America, the Caribbean and other nations are forced to take as a result of global economic inequality and desperate conditions in their home countries.

The strict immigration laws of the United States do not deter immigration, but rather force migrants into dangerous situations because they feel they have no other choice. For migrants undertaking this journey, the stakes are high and the outcomes uncertain: some arrive to the border and are allowed into the United States, while others are left behind, deported, or stranded in Mexico. For some, the journey in search of the “American dream” becomes a nightmare.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera is Associate Professor in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University. Her areas of expertise are Mexico-U.S. relations, organized crime, immigration, border security, social movements and human trafficking. She is Past President of the Association for Borderlands Studies (ABS). She is also Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and non-resident scholar at the Baker Institute’s Center for the United States and Mexico (Rice University). Correa-Cabrera is co-editor of the International Studies Perspectives (ISP) journal.

Jaime Scott is a J.D. Candidate at the University of Arizona. She graduated from George Mason University with degrees in Government and International Politics and Spanish in the Spring of 2021.

David Riedel also contributed to the project. He holds an MA in International Commerce and Policy at GMU and is currently a Management and Program Analyst at the U.S. Department of Commerce, Economic Development Administration.