Two months after the anti-corruption candidate Bernardo Arévalo’s surprise electoral victory in Guatemala, the country’s political future—specifically the question of whether Arévalo will ever be able to assume the presidency he won in a landslide—remains unclear. This mixture of progress and retreat is a familiar, bittersweet story in Guatemala. From 2006 to 2019, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) dismantled dozens of entrenched criminal enterprises and spurred hopes for greater reform in the legal system. The historic conviction of former president Efraín Ríos Montt in 2013 demonstrated that even political figures thought to be untouchable could be held to account for their crimes. In 2015, a nationwide protest spanning ethnic and class sectors brought the corrupt regime of Otto Pérez Molina crashing down.

However, the deep-seated and well-connected forces of corruption and impunity have always responded, checking the progress of reforms. Ríos Montt’s conviction lasted for less than two weeks before the oligarchy intervened in the judicial process, leading to a reset of the trial that allowed the genocidal ex-general to spend the remainder of his life free at home. CICIG was abolished, its staff persecuted or driven to exile, and other anti-corruption officials have likewise fled the country in fear for their lives.

The same public that brought down one corrupt president turned to the political outsider candidate Jimmy Morales, whose slogan “not corrupt, nor a thief” would quickly prove false, but was just the right message at the time. Morales’ involvement in corruption attracted the attention of CICIG, and he responded by unilaterally terminating the commission’s mandate and barring its leader from returning to Guatemala. He also appointed Consuelo Porras as the new attorney general, ensuring that he would have nothing to fear from Guatemalan anticorruption investigations. Porras set to work immediately, dismantling Guatemala’s nascent efforts to stamp out impunity. She brought the full power of her ministry to bear in punishing the agents and judges who had worked to investigate and prosecute organized crime, and earned herself a sanction from the United States as a “corrupt and anti-democratic actor.”

Guatemalans of every social class and ethnolinguistic community recognize that corruption and impunity are the root causes of their country’s endemic problems. From daily irritations like petty crime and bureaucratic corruption to life-altering catastrophes like kidnapping, extortion, and murder, Guatemalans have learned the frustrating reality that their government does little to prevent or prosecute the violence they continue to endure in this era of the “post-conflict.”

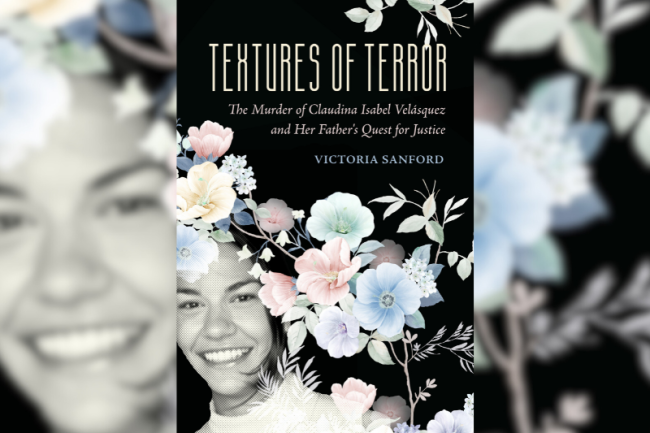

Victoria Sanford offers a thoroughly documented, intimate portrayal of Guatemalans’ pain, struggle, and frustration in Textures of Terror: The Murder of Claudina Isabel Velásquez and Her Father’s Quest for Justice. The book combines several threads of Sanford’s research over the past twenty years, covering a lot of history and social context in an accessible and human-centered approach. The tragic murder of a 19-year old law student, Claudina Isabel Velásquez, offers a point of departure for Sanford to bring Guatemala’s epidemic of feminicide into focus. Sanford presents the brutal scale of the epidemic of violence against women to reveal the horrific frequency and routine nature of such deaths in Guatemala, where two Guatemalan women are killed every day, and 98 percent of cases are not solved by police. She shifts between ethnographic case studies of women from different backgrounds—capital city and highlands, Maya and Ladina, extreme poverty and middle-class—to portray the life and personality of the human beings who are otherwise lost in the dire statistics.

We meet “Esperanza” from the western Highlands, a Mam Maya woman who was sold into forced marriage at age 12 and only escaped by fleeing to the United States. Esperanza’s case makes it clear that violence against women became routine during the state’s genocide against Indigenous communities, and few protections have evolved to respond to the problem. Going to the police for help was never a consideration—she didn’t have money to pay them a bribe for assistance. From “Magda,” a Ladina woman married to a K’iche’ Maya man in a rural community, we see what happens when women attempt to use the police and justice system for protection. Although Guatemala has specific laws to prevent violence against women, local magistrates do not regularly apply these laws, leaving women subject to the whims of police. Sanford points out the vast gulft between statistics showing that the government takes steps to address violence and the actual experience of women on the ground, for whom a restraining order has no practical effect and brings no additional support. Like Esperanza, Magda also fled to the United States in search of safety for herself and her child.

Sanford was exceptionally well-positioned for the work, able to draw together an international network of scholars and experts to work on behalf of Claudina Isabel’s family and other high impact human rights cases. Her own academic background included working with the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation, addressed in greater detail in her 2003 Buried Secrets: Truth and Human Rights in Guatemala. The connections she built through this work—to expert witnesses in the forensics community and lawyers specializing in human rights cases—allowed her to bring attention and resources to cases in Guatemala that would otherwise never be properly addressed. Drawing on her network of expertise in forensics and investigation, Sanford details the systemic failures of government agencies at every step in the pursuit of justice for Claudina: from startling errors in basic crime scene investigation around the discovery of Claudina’s body, through careless procedural flaws and miscommunications between agencies that could potentially derail criminal prosecutions in the future, to the passing of Claudina’s case between dozens of personnel and offices over the course of a decade with little progress toward a resolution. Sanford described this shuffle of case files as an example of the “bureaucratic proceduralism” that allows officials to carry on the appearance of working without actually pursuing investigations that would challenge the status quo of impunity.

Sanford provides a historical overview of Guatemala in the late 20th century, acknowledging the roots of contemporary violence in the genocidal conflict of the 1950s-90s. The military’s frequent application of violence against civilians, particularly Indigenous communities, led to a routinization of intrafamilial violence that has lasted long after the Peace Accords were signed in 1996. The transition to democracy allowed former military officials to continue exerting wide influence over the state. The cancer of illegal and clandestine groups spread throughout the government, leading the United Nations to call for the unprecedented establishment of CICIG to help the Guatemalan justice system root out corruption at the highest levels. Sanford shows the direct links between feminicide and wider forms of violence in a society where impunity reigns.

She further ties this hopeless situation to the rise in migration to the United States. The popular protests that brought down the corrupt Perez Molina government were followed by a steep decline in migration; however, when the subsequent Morales and Giammattei administrations revealed their allegiance to entrenched corruption, migration sped up. For women, in particular, the near certainty that violence will not be prevented, addressed, or investigated by the Guatemalan authorities—i.e., the 98 percent of cases that are never resolved—seeking refuge in the United States is the most sensible option. Indeed, the only women profiled in Sanford’s book who escape the cycles of violence are the ones who made it to the United States.

While Sanford is focused on explaining the historical context of feminicide, the same details reveal many of the forces at play in the current stand-off between civilian protestors and the Guatemalan government. The Attorney General, Consuelo Porras, was appointed by Morales, the president who abolished CICIG to avoid his own downfall for corruption; she replaced Thelma Aldana, who fled into exile while running for the presidency, and who was barred from running in the recent election. Aldana’s exclusion prompted many voters to spoil their votes or vote "null," leading that category to first place in the election. Many of the same voters returned to choose Arévalo in the runoff. In response, it was Porras’ public ministry that launched investigations into Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party, including ordering the National Congress to disband the party and issuing arrest warrants for the party’s founders. More recently, agents of the public ministry raided ballots from the offices of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, in some cases ripping the boxes from the arms of the protesting judges. The protestors blocking highways across Guatemala call for several goals, but one commonly shared demand is the resignation of Porras.

Altogether, Sanford has woven Textures of Terror into a testimonio that draws on the emotional power of the stories she witnessed to demand a response to the larger tragedy of feminicide in Guatemala, and the ongoing refusal or impossibility of the government to address it. The best hope for change now rests in the fate of the Arévalo presidency, and the thousands of Guatemalans fighting to make sure their votes are respected.

Doc M. Billingsley is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Sustaianbility Minor at Elmira College in upstate New York. He is currently working on a book about historical memory and social movements in Guatemala.