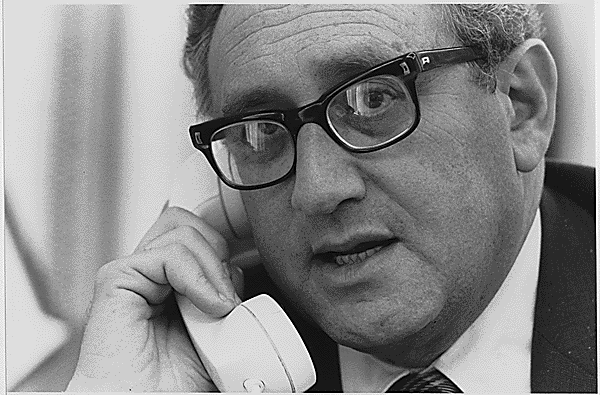

On November 29, 2023, Henry Kissinger died at the age of 100. On November 25, 1970, at the age of 47, he was plotting the death of Chilean democracy. On that day, he wrote a memo to President Richard Nixon on the U.S. government’s ongoing efforts to destabilize the administration of President Salvador Allende.

“The program has five principal elements,” he explained. It included: (1) Political action to divide and weaken the Allende coalition; (2) Maintaining and enlarging contacts in the Chilean military; (3) Providing support to non-Marxist opposition political groups and parties; (4) Assisting certain periodicals and using other media outlets in Chile which can speak out against the Allende Government; and (5) Using selected media outlets [redacted] to play up Allende’s subversion of the democratic process and involvement by Cuba and the Soviet Union in Chile.

As Kissinger saw it, Allende was an especially nettlesome problem for Washington. He was a stalwart member of the Chilean Socialist Party and the candidate of a left-wing coalition known as Popular Unity (Unidad Popular) that prevailed narrowly in the 1970 election. Allende’s was “the first Marxist government ever to come to power by free elections,” Kissinger lamented in writing in early November 1970. “He has legitimacy in the eyes of Chileans and most of the world; there is nothing we can do to deny him that legitimacy or claim he does not have it.” As he reminded his president, the United States technically supported the sovereignty of independent nations in the Western Hemisphere, rendering it “very costly for us to act in ways that appear to violate those principles.” When it came to Allende’s Chile, Kissinger recognized that “Latin Americans and others in the world will view our policy as a test of the credibility of our rhetoric.”

But credibility on that front risked discredit on another: “Our failure to react to this situation risks being perceived in Latin America and in Europe as indifference or impotence in the face of clearly adverse developments in a region long considered our sphere of influence.” In Kissinger’s view, Chile in the early 1970s placed two U.S. foreign policy commitments into diametric opposition: on one hand, support for democracy abroad even when its workings delivered results that displeased Washington and, on the other, the assertion of undisputed primacy in its putative sphere of influence. This, of course, was not the first place where U.S. foreign policymakers would have to weigh these competing priorities, nor would it be the last. Kissinger ultimately urged Nixon to “oppose Allende as strongly as we can and do all we can to keep him from consolidating power, taking care to package those efforts in a style that gives us the appearance of reacting to his moves.” Undermine, attack, and then blame the victim—these were go-to moves during his time as national security advisor and then secretary of state.

As critical obituaries have noted, Kissinger is notable for the widespread human devastation he enabled. Ignominious standouts include his concerted campaign against Allende, which set the stage for the rise of barbarous General Augusto Pinochet to power, and the illegal bombing of hundreds of thousands of civilians in Cambodia. “It is an act of insanity and national humiliation to have a law prohibiting the President from ordering assassination,” he once said, leading all of those who survived his time in power to wonder what more havoc he might have wreaked with no such prohibition in place.

Also notable, however, are the arguably more plentiful ways in which Kissinger was unremarkable. Like so many other callous Washington courtiers over the years, he time and again displayed withering contempt for the idea that the powerful can and should be constrained by democratic safeguards.As he once revealingly joked (wink wink), “The illegal we do immediately; the unconstitutional takes a little longer.” The idea that people outside the United States are entitled to autonomy also offended him. “I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people. The issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves,” he asserted in 1970.

Like so many creatures of Washington before and after him, Kissinger frequently prioritized his own reputation. “Mr. Kissinger’s concern is not for the Cambodians, who want no more war,” as Anthony Lewis put it in The New York Times in 1975. “It is for American credibility, and especially his own, which he thinks would suffer if we ‘lost’ Cambodia. Because the only conceivable settlement now would mean [President] Lon Nol’s departure, the war must go on. Mr. Kissinger is prepared to fight to the last Cambodian.” Kissinger saw his professional standing in that instance depended on the death of faceless men, women, and children abroad. He was not unique in his indifference to non-American life.

And yet Kissinger embraced a morbid noblesse oblige vis-à-vis the U.S. on the world stage, a vision that comes into focus in a 1972 interview in which he proclaimed that “Americans like the cowboy…who rides all alone into the town, the village, with his horse and nothing else…This amazing, romantic character suits me precisely because to be alone has always been part of my style or, if you like, my technique.”

After the violent fall of Allende, who killed himself during the coup that smothered Chilean democracy for a generation, Kissinger told Nixon that “in the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.” In explicitly placing Chile’s traumatic experience in 1973 within the same lineage as Guatemala in 1954 (and, indirectly, Iran in 1953), Kissinger reminds us that he was but one player in the tragedy of U.S. Cold War foreign policy. Indeed, for a man likely to be celebrated in numerous obituaries as a statesman of extraordinary distinction, Kissinger was not exceptional in the least in how he resolved the frequent tension between democracy abroad and the prerogatives of U.S. hegemony. When push came to shove, fuck democracy. In that regard, there was nothing special about him.

Andre Pagliarini is Elliott Assistant Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College, a fellow at the Washington Brazil Office, and non-resident expert at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. He is writing a book on the politics of nationalism in modern Brazil.