Leer este artículo en Español.

Pedro Uc has lived most of his sixty years in or near Buctzotz, a Maya town 90 kilometers from Mérida where his ancestors have lived since time immemorial. Known for his poetry and writing in Mayan, Uc is also a committed activist who has been promoting and working to protect his culture and his peoples’ communal land rights for decades.

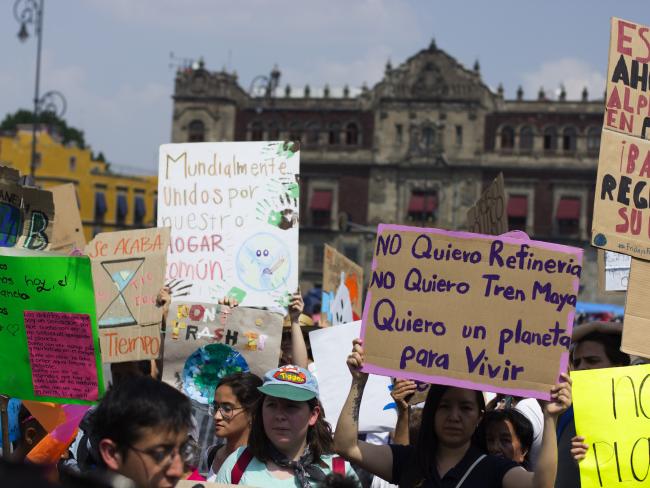

There is little that could surprise the seasoned activist, whose local knowledge and roots run deep. But the pace of change brought on by the misnamed Maya Train has gone beyond his wildest fears.

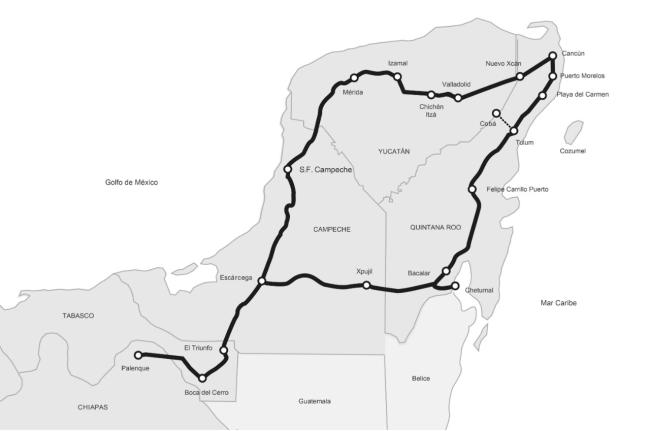

“More land has been sold over the past three years than in the fifty years previous,” said Uc in a phone interview from Buctzotz. The frenzy of land speculation Uc describes has been brought on by construction of over 1500 kilometers of train tracks on the Yucatán peninsula, part of a megaproject promoted by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO).

A Frenzy of Expropriations

Over the last two years, Mexico’s federal government has expropriated over 15,000 hectares of land for the Maya Train. Much of that territory was ejidal, or communally owned land, and a fraction of it was privately owned. Each hectare is purchased at prices well over market rates, driving up land prices throughout the region and displacing local communities. New expropriation decrees appear regularly in Mexico’s parliamentary gazette.

On Monday, July 10, for example, two decrees expropriated over 138 hectares from two ejidos in Bacalar, Quintana Roo, and a third expropriated 94 private properties in areas where the train line is to be built. A fourth decree expropriated over 1,500 hectares of ejidal land in Felipe Carrillo Puerto, in the same coastal state, for construction of a military base and the new Tulum Airport.

Private investors and speculators are also seeking to profit from rising land values. Uc describes the process by which communal landowners are convinced to sign over their property as filled with cash payments, promises, individual rewards, and sometimes even threats.

“First the people are invited to participate in the great Maya Train project, and their participation is going to consist in offering up their land, they’re told they’ll get jobs, and they’re doing a big favor to the world because they’re helping connect the Peninsula to the rest of the country,” said Uc.

“The narrative is the same as always, which is that life will improve for the communities; if the people don’t want that then the ejidal leaders are sought out and corrupted by FONATUR,” Mexico’s federal tourism agency. Many are happy to sign over their lands, but others are not.

Should there be any holdouts who continue to refuse to sell their land so it can be used for the megaproject, another key actor enters the frame: the Mexican army.

“If the people still refuse to be corrupted, they’ll get a few visits from the army and they’ll be threatened and told to hand over their land,” said Uc. Fear means that few have spoken out about these kinds of threats, which Uc maintains are not isolated events.

Social Anthropologist Ivet Reyes Maturano echoes Uc’s concerns when it comes to the military’s role in the megaproject. “The energy projects were megaprojects run by large industries, and it was very impressive… They had a whole system set up to disorganize and counter local organization,” said Reyes Maturano, who is a member of the grassroots organization Articulación Yucatán.

“To see the state apparatus together with militarization is really scary, and it’s a geopolitical change we hadn’t previously seen, which fits with the logic of the expansion of capital and the explosion of drug trafficking.”

Everything Old is New Again

The idea of railways connecting—and transforming—Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula is not new.

During the last decades of the 19th century, five different rail lines were laid across the peninsula, spinning out like a spider’s web from the city of Mérida. Unlike in other parts of Mexico, the Porfirian-era tracks in Yucatán and Campeche states weren’t financed by English or U.S. companies, rather, they were built and administered by local elites looking to get henequen to market.

Henequen—an agave fiber then known as green gold—was the peninsula’s key export commodity until the early 20th century. It made a handful of families extremely rich, while subjugating Indigenous Maya as well as migrant laborers to conditions U.S. journalist John Reed famously likened to slavery.

Then—as now—the construction of railways was about more than transportation. Historian John Coatsworth argues that the expansion of train tracks throughout Mexico during the long rule of Porfirio Díaz was a central catalyst in bringing about the liberal dream of privatizing Indigenous communal land.

It’s been almost fifty years since the United Yucatán Railways fell into disuse, and almost as long since powerful men in Mexico City have proposed to re-invigorate investment and transform the region.

Partway into his presidential term in 1990, Carlos Salinas promoted the “Proyecto Mundo Maya,” a mass tourism project similar in many respects to the Tren Maya. A decade later, Vicente Fox’s Plan Puebla Panama foresaw the revival of a railway corridor through the Peninsula.

But it wasn’t until López Obrador took office that the longstanding dream of modernization and territorial reorganization for the Yucatán Peninsula became a reality.

A Piecemeal Approach to a Signature Megaproject

Rapid fire consultations with local residents were held over a month-long process at the end of 2019; little was known about the project at the time. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNCHR), which was invited to observe the consultation process, disavowed the vote, finding they did not meet international standards.

“The Maya Train has been reduced to the issue of transport and train lines, it’s been divided up and fragmented,” said Jazmín Sánchez Arceo, an environmental engineer at the University of the Yucatán. “Even their own environmental impact statements are organized into separate lines, and the project as a whole, which is about social and territorial reconfiguration, is not being properly addressed when it’s reduced to just the tracks.”

Local activists and scholars are concerned about the disruptive potential of the megaproject—which includes 21 stations and new tourism infrastructure—to sensitive ecosystems and geologies. They’re also aware of how it connects with other powerful interests in the region.

“What we’re seeing is that it is a catalyst and could become part of a much stronger push towards the kinds of extractivism that we’ve been seeing in the peninsula over the past few years,” said Sánchez Acero, who is also part of Articulación Yucatán.

Articulación Yucatán is a coalition of scholars and activists dedicated to what they refer to as the translation of technical information for a non-specialist audience through presentations with local communities and ejidos, as well as online.

Recent studies by members of Articulación Yucatán explore the impacts of the Maya Train on biodiversity and ejidal land, and of how the project’s promoters have minimized complex territories and lifeways by using a developmentalist discourse of progress.

A Military Train with a Geopolitical Purpose

Although their participation wasn’t announced until well after the sham consultations in 2019, soldiers and military engineers have already cut a deep sash through the dry rainforest of southern Campeche to build Line 7, and are working around the clock to complete the project before AMLO leaves office in 2024.

In total, the Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA) is building 553km of tracks for Line 5 (Cancún to Tulúm), Line 6 (Tulúm to Bacalar) and Line 7 (Bacalar to Escárcega). The military is expected to operate those sections of the train indefinitely, as well as providing security for the entire project and rebuilding and managing three local airports.

To date the Secretary of National Defense has been granted over 6,500 hectares of land in the peninsula via expropriation. The Mexican media has reported that it is building an unauthorized hotel less than 10km from the archeological site and biosphere reserve at Calakmul.

“This project is not presented or designed in benevolent terms, in terms of development or the needs of communities within this territory,” said Sergio Prieto, a researcher and professor at the College of the Southern Border in the city of Campeche. “It’s thought of in terms of national security.”

Prieto says it’s important to consider the Maya Train and the suite of projects connected to it as part of a broader scheme for the region, which includes the Trans-Isthmus corridor, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific across the narrowest part of Mexico, and Sembrando Vida, a federal project encouraging individual farmers to grow marketable fruit and nut trees, often on communal land.

“These three huge projects are public, and their aim to a large extent is to penetrate and control this territory, this border region that has for the most part been marginalized and left outside of global or state dynamics,” said Prieto.

In addition to proposed industrial pork or chicken farms, solar and wind farms, new manufacturing plants, and tourism projects, there’s another key geopolitical interest served by increasing state control of Mexico’s south.

“This is the largest migrant corridor in the world,” said Prieto. “Increased control in this region also fits within the framework of externalizing the U.S. border.”

Dawn Marie Paley is an investigative journalist and author of Drug War Capitalism and Guerra Neoliberal. She is a member of NACLA's editorial committee.