This piece appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Leer este artículo en español.

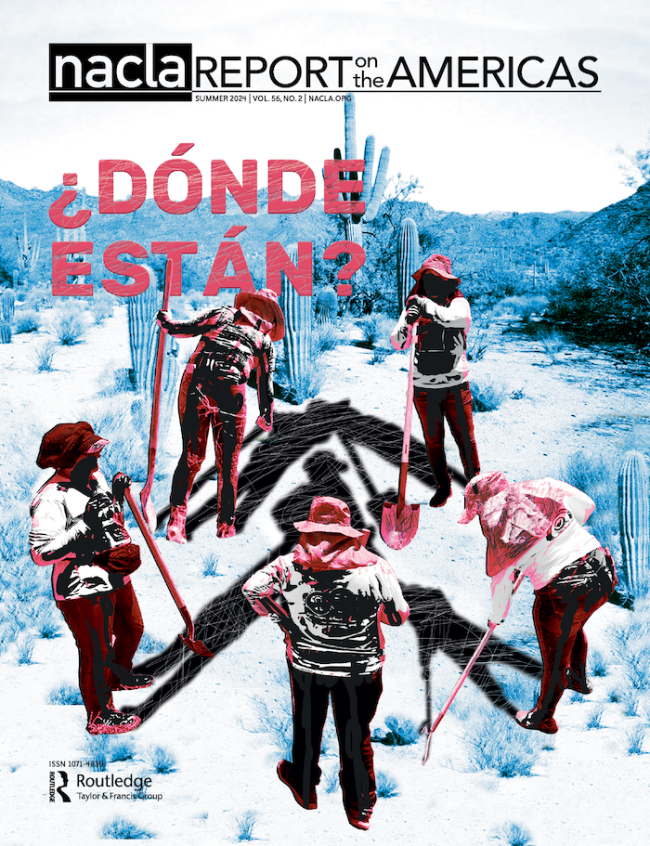

“Si no hay cuerpo no hay delito.” If there is no body, there is no crime. Thinking about crude impunity, as war and conflict rage across the world, has made writing this note quite difficult. The genocide of Palestinians and the wars in Ukraine, Sudan, and elsewhere are producing forms of social shattering that are felt globally: violence, disappearance, trauma, and indiscriminate death. The Americas, embroiled in its own regional conflicts, remains linked to the world’s upheavals as tens of thousands of migrants traverse places like the Darién or the Sonoran Desert with much human collateral. A lack of information on the whereabouts of missing individuals produces an abyss of meaning that we may never fill.

Meanwhile, human rights violations across the Americas continue to pile up. People’s dignity is habitually trampled, and in many places, citizens are snatched up from their places of study, leisure, and work. Beyond migrant disappearance, the multidimensional phenomenon of disappearance is found in the emergency of feminicide, the extermination of Indigenous lifeways, or in the targeting of racialized land defenders mobilized against capital’s extractions. Disappearance is cancerous—spreading, accelerating, and mutating, becoming harder to trace.

As rising authoritarianism throws societies further into political and social chaos, this issue of the NACLA Report on the Americas excavates how disappearance has reemerged—or persisted—as a dependable technique of terror, social control, and revisionism. Across the region, societies now facing an erosion of their human rights protections are the same societies that remain indelibly marked by past episodes of militarized repression. This issue also explores these legacies—disappearance’s afterlife—from the ongoing forms of disappearance that impede truth and justice, to the ways families and advocates continue to resist erasure.

This issue underscores that disappearance touches the entire region. Like coloniality, which tethers the region together despite national particularities, disappearance cuts through the societies of the Americas, telling us much about the pain, grief, and emotional life of the region’s struggle for justice. Our relied-on forms of narration, via language, statistics, methodology, and even art, struggle to fully capture the scale of atrocity. In its multivalent form, having a cluster bomb effect, disappearance is thus more than a mere phenomenon: it has a structuring power that is spectral and deeply material, vacillating between the forensic and the abstract.

Between Life and Death

The Americas remain trapped in a cycle of violence where disappearance has operated as a pressure valve to flush away social and political problems. From the violent making of the modern Americas to the well-trodden Cold War-era stories of clandestine torture centers, anticommunist massacres, and “subversives” being thrown into the sea, the long list of sustained social murdering has defined the psychic and emotional lives of entire generations. Even today, the same ghastly continuum of racial, political, and quotidian violence reverberates in the drug war necropolitics that Dawn Paley terms “neoliberal disappearance.” Still, state and military leaders deny responsibility, and these unresolved problems accumulate. Disappearance, then, is also attritional, producing mistrust in authorities and conditioning people’s relations in contexts where gangs, paramilitaries, and cartels define, alongside the state, the parameters of life and death.

Across distinct contexts, the objective of disappearance remains the same: to destroy the social fabric and preserve “order” by thrusting communities into immobilizing trauma. From a shared condition of loss, pondering life, practicing hope, and enacting solidarity become almost ornamental—distractions from the frenzy of surviving the everyday.

Attempting to cover this breadth, this issue captures the various practices of accounting for, defining, and locating the disappeared. Deliberately multidisciplinary and transnational, we bring together the perspectives of individuals, collectives, researchers, artists, and forensics experts. The issue shows how interlinked phenomena of violence not only establish ways of living and dying but also stimulate a multiplicity of responses that challenge the disappearance crisis and envision novel efforts in the pursuit of truth and justice.

Representing the Crisis

The articles in this Report offer a sample of the crisis of disappearance in the Americas, clustered around hotspots. Historically and now, Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and the Southern Cone are among the most acute zones.

From Mexico, architect and activist Sergio Beltrán-García tackles the representational crisis head on, discussing a unique project that responds to the limitations of official data and statistics to capture the complexity of disappearance. Beltrán-García shows how collective memory work with impacted families is necessary to support transitional justice. In a similar vein, artist-researchers Leonardo Aranda Brito and Dora Ytzell Bartilotti Bigurra discuss aesthetic strategies for examining disappearance, loss, and oblivion. From garment-making to searching-as-performance, the works they explore counter official narratives and offer new ways of engaging absence.

Probing further, I speak with anthropologist Jason De León about the politics of studying the disappeared, present-day migration, and the importance of rigorous interdisciplinary scholarship. For De León, we cannot understand the region without getting our hands dirty, thinking outside the box, and establishing an ethical relationship with the subjects we study.

Turning to Central America, journalist Kenny Castillo and scholar Cristian Padilla Romero look at the case of four missing Garífuna men within the community’s long struggle against targeted displacement and extermination on Honduras’s Caribbean coast. From Guatemala, El Faro’s Roman Gressier recounts the story of the Diario Militar, a leaked dossier that details the systematic disappearance of nearly 200 targets during the height of the internal conflict. As retired officials now stand trial, Gressier digs into the structural limits to justice and the systematic obstruction of society’s right to truth.

In a roundtable dialogue, I talk with representatives of advocacy and political groups in El Salvador. Yaneth Martínez of Cristosal and Ana Julia Escalante of Pro-Búsqueda speak about wartime disappearance, transnational adoption, and arbitrary detention; Jaime López and Pablo Benítez, militants of Escuela Política, take stock of how Nayib Bukele’s state of exception impact movement-building and truncates post-war political alternatives.

In an autobiographical piece, Nelson De Witt/Roberto Cotto reflects on his experience as one of “the disappeared”—an internationally adopted child—from El Salvador’s civil war. Compellingly weaving a transnational story of his adoption, De Witt/Cotto recounts how he came into consciousness of this identity within the maelstrom of U.S.-Latin American history. In a web exclusive companion piece, Nathan Rossi explores how transnational adoptees from Central America make sense of their lives through multimedia storytelling, using film, photography, and artmaking to help heal and “un-silence” the disappeared.

In Colombia, Oscar Pedraza, a research fellow with Forensic Architecture, narrates how an investigation into the 1985 siege at Bogotá’s Palace of Justice coupled forensic analysis, modeling, and thinking with “negative space” to yield new information about a key, missed site of military activity. Activist Jhon León and scholar Anna Wherry report on how Colombian ex-combatants now aid families in searching for their disappeared. Beyond locating remains, this collaborative searching uncovers stories that more fully represent the lives of the missing in their complete humanity.

In a web exclusive photo essay, journalist and curator Angélica Cuevas-Guarnizo relates the experiences of the Mothers of Soacha, who collectively revealed Colombia’s “false positives” scandal by calling attention to the extrajudicial killings of local young men. Exposing the limits of state redress, Cuevas-Guarnizo shows how body art, memorials, and other practices of presence enable the Soacha mothers to intervene in public space and challenge impunity. Broadening understandings of disappearance, artist-scholar Hannah Meszaros Martin’s work on herbicide use and fumigation campaigns points out the processual, earth-laden, nature of disappearance, underscoring how “the environment becomes both the target and the very medium through which violence is conducted.” Disappearance, Meszaros Martin illustrates, is not solely human-focused, but also produces multispecies and habitat loss.

Across the Americas, gendered violence continues to be a dominant form of “doing” disappearance. In Peru, anthropologist María Eugenia Ulfe powerfully explains, women’s bodies are an archive of violence whose veracity is routinely denied, silenced, and vacated of possibilities for redress. From the Peruvian armed conflict to the present, Indigenous women from rural zones bear the brunt of the violence, both as targets themselves and as searchers for their disappeared relatives.

Moving to the Southern Cone, a pair of web exclusives present two sites for understanding the struggle over local memory of the disappeared. In Chile, Constanza Dalla Porta narrates the national scandal of Patio 29, a Pinochet-era mass gravesite where bodies were misidentified, leading families to mourn the wrong remains. In Paraguay, Marco Castillo connects the disappearance of countless “enemies” of dictator Alfredo Stroessner’s long reign to the transnational eliminatory logic of the U.S.-backed Operation Condor. Together, these two pieces underscore the unending quest for clarity, historical truth, and recognition to overcome the terrors of the past.

From Argentina, journalist Gary Nunn reports on Tehuel de la Torre, placing this disappeared trans man within the long arc of anti-trans violence reaching back to the dictatorship. Nunn examines how Argentina risks further invisibilizing transhomicide and travesticide if President Javier Milei rolls back key victories for gender and sexual equality. Against Milei’s denialism, researchers Malena Nijensohn and Luciana Serrano stitch an intergenerational history of women-led public politics that ties the legendary struggle by the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo to the mass feminist movements of today.

Finally, our poetry section contains moving works from Maryam Ivette Parhizkar, Ojo Taiye, and Daniel Borzutzky that engage loss, witness, and the politics of life and death.

Vital Struggles

Taken together, this issue of the NACLA Report presents disappearance as an all-encompassing crisis that impacts life in a multiplicity of ways, from the realms of institutions to the depths of the intimate. These cases—of which there are countless more—remind us to recalibrate our justice horizons and ensure that we remain whole to effectively engage in the vital struggle of transforming our aches and our grief into sources of strength and conviction. Across the cities, countrysides, jungles, and deserts of the Americas, collectives continue to stubbornly search for their people and reject being made into what Jean Franco called “disposable life.” Through a popular politics of presence, these quests for justice and closure challenge impunity to powerfully reclaim the disappeared from the abyss of the unknown.

Jorge E. Cuéllar is a scholar of politics, culture, and daily life in modern Central America. He is an assistant professor of Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies at Dartmouth College and a member of NACLA’s Editorial Committee.