This piece is part of our Spring 2022 issue of the NACLA Report.

Leer este artículo en español.

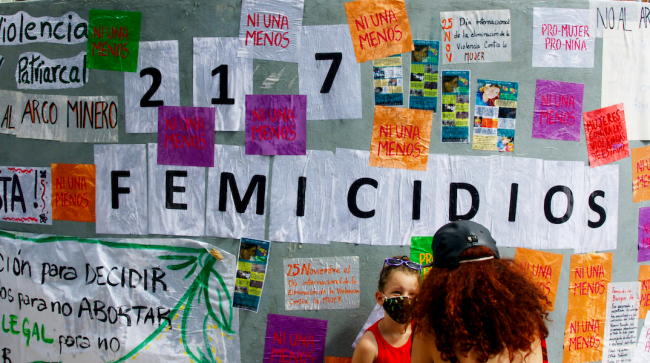

At the beginning of the 21st century, Chavista governments introduced various laws and decrees that represented gains for women. As feminist scholar and activist Giaconda Espina has noted, the reincorporation of measures to protect victims of gender violence from their abusers in the 2007 Law on the Right of Women to a Life Free from Violence came as a win for a movement that united different historical currents within Venezuelan feminism. The same law, through a 2014 reform, also typified femicide as a specific crime representing “the extreme form of gender violence.” However, there remain many criticisms of the ineffective protection of women and their rights in Venezuela, particularly given the lack of response from the justice system. According to the Venezuelan Observatory for the Human Rights of Women, of 58,241 cases of gender violence presented to the public prosecutor’s office in 2011, only 2,165 or less than 4 percent went to court, meaning impunity remains the norm around gender violence in the country.

Today, the weight of the deep and lasting Venezuelan crisis rests in large part on women, who bear the burden of daily caretaking while also facing the risks of gendered violence and the sexual and reproductive health issues that affect their bodies. In fact, the crisis has provoked significant increases in unwanted pregnancies and maternal mortality rates; shortages and prohibitive prices of contraceptives leave up to 70 percent of reproductive-age women without access to the means to prevent pregnancies and sexual infections. This is the reality in a country where abortion is not only illegal but punishable by up to two years in prison.

In thinking about these 20 years of Chavista governments since the 2002 coup and their relationship with women’s rights and feminist demands, I spoke with Marisela Betancourt. A woman, migrant mother, and self-identified leftist, Betancourt describes her feminism as a response to personal experiences concerning her subjective and physical autonomy. She is a member of the organization 100% estrógeno, which focuses on promoting gender-sensitive training, providing legal assistance for women in vulnerable situations, and fighting for abortion rights. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Yoletty Bracho: In the text “La mujer, la mujer, la mujer” from his 2009 Las Líneas, Hugo Chávez wrote that “without the true liberation of women, the full liberation of the people is impossible.” How has Chavismo incorporated—or not—the issue of women’s rights in the government’s words and actions?

Marisela Betancourt: Chavismo’s rhetoric has pivoted around the principle of exceptionalism. That is, Hugo Chávez’s rise to power was the beginning of an innovative political process. In 2015, at an event with the National Union of Women (UNAMUJER), a national women’s rights organization created by the government, Nicolás Maduro summed it up: “Hugo Chávez had to arrive so that women could begin to occupy spaces, new spaces in the social, institutional, economic, and political spheres.” Chavismo monopolized leftist identity, and any other political force that tried to dispute this identity was immediately challenged by the government’s media apparatus and accused of being co-opted by the enemy.

As a political movement that preceded Chavismo, feminism is inconvenient for this rhetoric that always positions Chavismo as a pioneer. As a solution to this dilemma, Chavismo projected a gendered signifier on the people—the quintessential political subject of the national-popular processes of the Latin American Left—to speak of women of the people. In this way, poor Venezuelan women became key actors in the revolution, which was in contrast to the representation of other women, like bourgeois women. In fact, there has been a tendency in the last two decades to associate non-Chavista Venezuelan women with national betrayal and malinchismo (preferring the foreign). In government discourse, bourgeois women were not considered deserving of rights. Instead, they were characterized as not needing socialist rights advances, because Chavismo’s public policies to address gender inequalities have largely been limited to social welfare policies.

In that context, the spotlight given to women during the Chavista period focused on three areas: women as the vanguard at the foundation of the party, women as the source of life and family protection, and women in spaces of political representation.

Chavismo understands feminism essentially as giving handouts to poor women, which perpetuates gender roles through patriarchal ideas about motherhood. This perspective is clear in the content of public policies pertaining to gender and can be seen, for example, in the very names of legislation: Law for the Protection of Families, Maternity, and Paternity; Law for Promoting and Protecting Breastfeeding; and the communal council law for creating committees on family and gender equality. The government’s main initiatives right now are programs focused on humane birthing and breastfeeding. Even paid maternity leave is limited to women, denying gender equality in caretaking.

Government discourse constructs Venezuelan women as more resilient than men, and the feminist revolution provides tools for women to better resist the conditions of structural inequality and vulnerability, but not necessarily fight them. It is the “all-terrain” view of the Venezuelan woman, reproduced in the media and political discourse. This also reproduces a profoundly capitalist and patriarchal logic that views women as vessels of production: the production of children and of pleasure. It frames women as the sustaining force of the nation, the family, the economy, and now, the revolution. It’s also a form of blackmail that lauds women experiencing poverty and inequality, generating a sense of self-worth that shapes how they face hardships and connect with political power.

YB: The fights for women’s rights in Venezuela are thanks to the feminist movement that has been active since at least the 20th century. What relationship has Chavismo had with feminist organizations? What concrete connections exist between the feminist claims of Chavista socialism and the rights demanded by feminist organizations?

MB: Chavismo has remained in power amid high levels of polarization, but also high popularity. This hegemony has allowed it to lean on a warmongering logic and govern without alliances with other sectors. This dominance allowed it to assume it could win its battles without needing other groups. Moreover, the high levels of polarization and political violence meant the government saw women’s groups with shared demands as political enemies.

The advances in women’s rights under Chavismo have been tepid. In the early days of Chávez’s government, they promoted women’s political participation, but the spaces offered were mostly appointed national positions—that is, appointed by male leaders. The women who participated in local and rural politics and in grassroots party structures encountered countless obstacles, from political violence because of their gender to exclusion by those who used meritocracy as a misogynistic argument. For their part, the women who distanced themselves from the PSUV idea of what feminism should or should not be have been targets for attacks, accusations, and criminalization, putting women’s rights activism at risk.

The 1997 Suffrage Law stipulated a 30 percent gender quota for candidates, but the 1999 constituent assembly rescinded that principle, arguing that parity infringed on equality. Instead, it left the issue in the hands of the National Electoral Council (CNE). It was not until the 2021 regional elections that the CNE forced political parties to comply with the 30 percent candidate rule, but only at the legislative level. However, Chavismo has been the political force with the largest number of women representatives, as candidates, executive cabinet members, and heads of public institutions. This contradiction can only be understood as an effort to co-opt politically aligned women, who respond first and foremost to the party line. That’s why women’s political representation does not automatically guarantee public policies focused on gender.

This all shows us that political opportunities for the advancement of women’s rights can only be constructed by women—without conforming to election calendars and independent of the party interests fighting for electoral control.

YB: An essential right for women is the right to abortion. There have been several pro-abortion demonstrations in Venezuela, including the recent “green path,” in which feminist organizations of various political inclinations met to demand “the legal and social decriminalization of terminating a pregnancy.” These demonstrations have even addressed parliamentary committees in the past. However, we haven’t seen any changes in the law. On the contrary, activists who help people seek abortions continue to face repression, like in the case of Vanesa Rosales, the women’s rights defender who was jailed and tried for helping a 13-year-old rape survivor get an abortion. What are the hurdles to securing the right to abortion in Venezuela? What role has Chavismo had in erecting and dismantling these hurdles?

MB: Chavismo is a political process that brings together different forces, different schools of thought, and diverse actors, and in every Chavista government there have been opposing internal factions. From the beginning, Chavismo has had profoundly conservative elements, from its inherent militarism to the involvement of Norberto Ceresole—the Argentine sociologist who served as Chávez’s advisor and whose theories about the trifecta of army, leader, and people inspired Chavismo’s civic-military partnership—to the clear machismo within mid-20th century Latin American revolutionary processes. But Chavismo is also eclectic, which allows for a connection with a broader and more diverse electoral base.

When comparing the Chávez and Maduro governments, we can see that they occurred within different international contexts. The Latin American progressive wave encompassed much of the continent and generated pressure to achieve liberal social demands that were either absent or reverted under conservative right-wing governments. Today, the context is different; the rebellion has turned to the Right, as Argentine journalist Pablo Stefanoni shows in his latest book. What we have is a society that is afraid of uncertainty, the other, and the new, and up against a government finetuning its authoritarianism. In this context, conservativism has gained ground in Venezuela in recent years.

However, if there is something to uplift from the last two years, it is that as the country goes through a process of depolarization, feminists from different sectors have reached joint agreements. A recent example was an event for International Safe Abortion Day on September 28, 2021—it marked the first march for the decriminalization of abortion in Venezuela. It was a historic march in which feminists from different political backgrounds came together with shared demands. As society is finding common ground among those previously at odds, there’s an appreciation of the need for coexistence. And in the same way, feminists of different stripes are coming together. As the political poles thaw, diverse movements can understand that they share many common goals.

Yoletty Bracho is a PhD candidate in political science at the Université Lumière Lyon 2. She has studied the relationship between popular organizations and the state and works with Venezuelan migrant organizations in France.

Marisela Betancourt is a political scientist with experience in communication methods and public policy design. She is a feminist activist with the 100% estrogen movement and completing a masters at the Universidad de los Andes.