As midnight approached on December 31, 2023, the crowd that was gathered before the stage parted to make way for the parade.

At one end of the long and wide grass field at the center of Caracol Dolores Hidalgo in the Lacandon jungle in Mexico’s southeastern state of Chiapas, the Zapatista Liberation Army appeared: hundreds of young people in green and red fatigues and black ski masks, carrying ornamental batons; their gaze immutable, their stance fixed.

At the other end, a battalion of 50 young women in uniform who had been standing to attention beneath the stage began to move forward, marching in lockstep under the command of their leader.

Solemn silence. Even the mountain breeze seemed to be holding its breath.

And then it began. La cumbia.

To the strains of Los Angeles Azules’ “17 años”—a song about being the first boyfriend of an innocent young girl—the troops of the Ejercito Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) moved towards each other with flawless dance steps, shifting the rhythm slightly when the song changed to Celso Piña’s “Sobre el Rio,” and finishing with a wild, joyful shake to ska band Panteón Rococó’s “Globalizado.”

Many in the gathered crowd—members of the 12 Zapatista caracoles, or community gathering points, now in a process of transition, and supporters from throughout Mexico and the world—laughed heartily. The Zapatistas are well-known for subversive, playful displays, and this “military parade” was a rich riposte to the way the movement had been characterized in Mexico’s mainstream media since announcing a significant change to their organizing structure and struggle for autonomy from capitalism and state power. It was also notable in the current context of increasing militarization in Mexico.

The Zapatistas’ laid out their new direction through a series of 20 communiqués released between October and December and authored variously by the EZLN, the spokesperson Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés, “El Capitán” Marcos (formerly Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, formerly Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos), and Tercios Compas, the Zapatistas’ cultural and media production team. The ninth communiqué, released on November 12, specified that the 30 Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ in Spanish) would be dissolved, along with the 12 Good Government Juntas. The caracoles will continue, wrote Subcomandante Moisés, “but they will remain closed to the outside world until further notice.” The autonomous municipalities are replaced by thousands of grassroots structures, called Local Autonomous Governments (GAL), that will coordinate with hundreds of Zapatista Autonomous Government Collectives (CGAZ) in place of the 12 Good Government Juntas. Answerable to the CGAZ via the GALs will be the Assemblies of Collectives of Zapatista Autonomous Governments (ACGAZ), which will be mobile respondents to the needs of the CGAZ for additional consultation in decision-making.

The new structure is intended to reduce the distance between the communities and the decision-making authorities. As Moisés wrote, under the previous structure “the proposals from the authorities did not go down as they were to the people, nor did the opinions of the people reach the authorities.” Further, this new devolved, grassroots form of decision-making is intended to ensure “that our towns survive, even in isolation from each other.”

The town-level GALs are the locus of planning and decision-making; the CGAZ and ACGAZ “must be accountable to the towns and must find a way to meet their needs in Health, Education, Justice, Food, and those that arise due to emergencies caused by natural disasters, pandemics, crimes, invasions, wars, and the other misfortunes that the capitalist system brings.”

The plan, explained Marcos in the third communiqué, has a 120-year, or seven-generation, outlook. A long-term approach is a well-established principle in Indigenous knowledge, planning, and governance processes throughout the world.

Chiapas “in Complete Chaos”

National dailies and media channels were quick to attribute the changes to the reality in Chiapas described in by Subcomandante Moisés in the fourth communiqué: ‘’The main cities of the southeastern Mexican state of Chiapas are in complete chaos,” he wrote.

“The municipal presidencies are occupied by what we call ‘legal hitmen’ or ‘Disorganized Crime.’ There are blockades, assaults, kidnappings, ‘cobro de piso’ [extortion], forced recruitment, shootings,’’ the subcomandante continued, warning people wishing to attend the 30th anniversary that ‘’we want you to come, but we don’t recommend it.’’

“Organized crime drives Zapatistas out of Chiapas” reads the Milenio headline; “Crime in Chiapas displaces even the Zapatistas” in Reforma; “This is how the EZLN lost control of autonomous municipalities in Chiapas to the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel,” Infobae.

But news of the Zapatistas’ demise is greatly exaggerated.

To be sure, Chiapas is undergoing a disastrous expansion of paramilitary rule and violence, which has led of late to sensationalized scenes such as September’s parade of Sinaloa Cartel gunmen rolling through the town of San Gregorio Chamic near the border with Guatemala to a crowd apparently cheering the Sinaloa soldiers for liberating them from control by the Jalisco New Generation cartel. A repeat of this spectacle appears to have happened this month in the municipalities of Chicomuselo and Bella Vista, crossing the border into the mountains of the Sierra Madre. As journalist Ioan Grillo explains, both the Sinaloa and Jalisco organizations have taken over large parts of Chiapas, exploiting local conflicts to buy the support of political representatives and terrorizing townspeople into working for them and paying extortion fees. Popular destinations for tourists such as San Cristobal de las Casas and Palenque have seen gun battles and shutdowns and Zapatista communities have been targeted, occasioning the “Stop the war in Chiapas” national and international protests in June last year.

However, as the Zapatista’s October-December communiqués clearly say, the new structure and organization of their activities has been in gestation for the past three years, and it takes a much longer view than the recent calendar of violent events in the region.

The new structure and direction are a response to “la tormenta” (the storm) of global climate change, political disintegration, and wars of depopulation, writes Moisés in the final communiqué.

It is ‘’a path to cross the storm and reach the other side safely,’’ drawing on their continuing survival as Indigenous peoples that have already faced the apocalypse of colonization since the arrival of the Spanish five centuries ago. At its center is a new experiment in property ownership—that is, ‘’non-ownership of land.’’ Some of the land recuperated by the Zapatistas in the past 30 years will be thusly repurposed, established as “land without papers,” with “a few hectares of this Non-Property…. proposed to sister nations in other geographies of the world,” “to come and work those lands, with their own hands and knowledge,” and/or to learn the knowledge of the Zapatistas.

This program of “Non-Property” joins the devolution of governance described above in a concerted effort to survive the storm of capitalism and colonialism in its newest forms. This is described as the climate change that has crops blooming and dying in the wrong places and animals born at the wrong time, and the social chaos of “disorganized crime” operating in a death-lock with structural state violence.

As Marcos retorts in the fifth communiqué, the effects on the Zapatistas of the recent uptick in “narco-violence” in Chiapas is all too easily reduced to the familiar story of social division of Indigenous communities through counterinsurgency of one kind or another—the multiplying wars of territorial control in Guerrero and Michoacán, for example, and the mass migration of children and young people to the United States that has emptied pueblos throughout the country. ‘’Any Indigenous person who is not like the anthropology manual says is a narco,” El Capitán mocks, in response to a Televisa report that claimed, via an interview with anthropologist Gaspar Morquecho, that the autonomous communities had been disintegrated by drug cartels.

Facing the Future with Cumbia and Postcolonial Comradeship

As the dancing militants ended their performance, the crowd gathered once more before the stage. At around 2,000 attendees, the gathering was much smaller than previous Zapatista encuentros, and visibly populated by a similar style of national cultural and academic figures and international guests from the United States and Europe, who joined the numerous delegations of Indigenous communities affiliated with the National Indigenous Congress. The field was ringed by hundreds of parked bicycles used by the communities’ health and education promoters.

Under the hum of a journalist’s drone camera, Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés began his address—a discourse on the future of the movement in Tzotzil, a Maya language that Zapatistas have in common. He stood flanked by empty chairs marked for the parents and relatives searching for disappeared persons throughout Mexico, political prisoners, and murdered children and young people, as well as altars in memory of deceased Zapatistas such as Comandanta Ramona.

As music and dancing continued well into the first hours of 2024, Zapatista members guided guests to sleeping quarters in the caracol and elsewhere in Zapatista territory, to sleep under the stars or on the floor of old stables and other installations on reclaimed ranchland. This also served as a quiet reminder to guests of what is at stake: land for those who work it and the possibility of life lived in common, outside five centuries of unequal and exploitative accumulation by violence, as part of a movement that has been held together by extraordinary discipline and a certain moral authority among many Mexicans and long-time international supporters. Since declaring war on the Mexican government in the uprising of 30 years ago, the Zapatistas have occupied thousands of hectares of land in Chiapas, defending it without the use of arms since agreeing to a ceasefire in 2006 and a host of long-awaited land tenure agreements, many still in dispute. As journalist and filmmaker Diego Enrique Osorno reports in El Pais, the land of and around Caracol Dolores Hidalgo itself was recovered when its three ranchers, all notorious for local abuses, fled after the 1994 uprising.

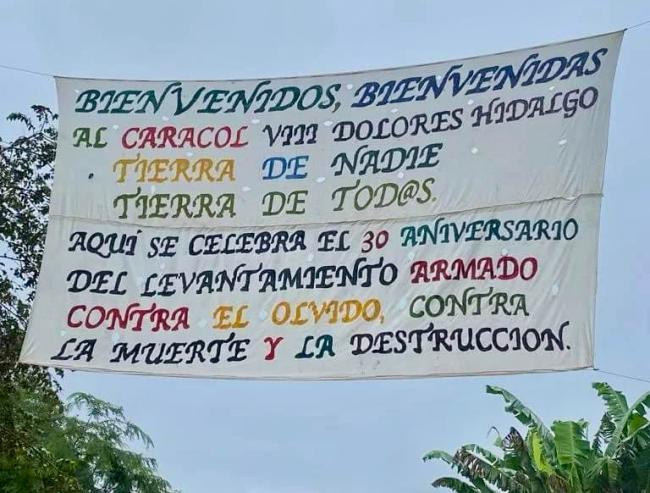

Gesturing to the kind of realpolitik that may be needed in the turbulent times ahead, Subcomandante Moisés in his speech made the point that ‘’we do not need to use violence but we will defend our land if we are attacked.’’ Here, the emerging proclamation of Zapatista land as “nobody’s land” takes on another strategic cast: land cannot be bought, sold, invaded, contested, or stolen if it belongs to no one. The anniversary guests were welcomed to this land with a sign reading, in part, “Tierra de Nadie, Tierra de Tod@s” (No Man's Land, Everyone's Land).

The celebrations in Caracol Dolores Hidalgo, which ran from December 30 to January 2, served as a wellspring of energy and strength for the time ahead that is rooted in long and faithful memory. Emphasizing arts and culture, various groups of Zapatista youth performed theater and music, such as a chronicle of the continuing failure of electoral politics in Mexico to represent and support the people, with programs such as Sembrando Vida—a pet project of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to address rural migration and environmental degradation—firmly in sight. On December 31, delegations from the National Indigenous Congress also presented musical and theater works, while on January 1, allies were invited to present their own works including an evening screening of Diego Enrique Osorno’s film La Montaña, a documentary of the Tour for Life, and an account of the voyage by sailboat of a Zapatista delegation—two men, four women, one non-binary person—across the Atlantic to Europe.

Moisés and Marcos both write of the international connections strengthened and evaluated during the transatlantic trip, which served as a symbolic reversal of the passage of European colonists to the Americas in the age of empire in the midst of the second year of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the “developed” West of “progress,” Moisés notes in the 20th communiqué, the delegation found that activists, organizers, and communities are seeing “the same… storm” of war, climate change, and criminality experienced by the Zapatista communities; an observation that is perhaps linked to the new invitation to outsiders to come and share knowledge and learn from the Zapatistas. “Thanks to these brother peoples we were able to broaden our vision, make it wider,” continues the subcomandante. As more of the rest of the world comes to see the precarity of the planetary situation, and the movement engages more proactively with outsiders in an exchange of knowledge and experience, the next 120 years may be the movement’s most cosmopolitan yet.

“If there still is a world in those dates, anyway,” wrote Moisés of the New Year celebrations, adding, “see for yourself.”

Ann Louise Deslandes is an independent journalist, writer, and research consultant in Mexico.