Report

Last October I arrived in Venezuela a few days prior to the election to try to get a sense of what people where thinking and—since I work for a union—what labor conditions were like in country.

Venezuela’s regionally orientated foreign policy during the Chávez era opened up autonomous policy space for other states in Latin America and the Caribbean. The concrete achievements of a number of mechanisms, including counter-trading and credit provision within the PetroCaribe framework and the recent establishment of a virtual regional currency, the SUCRE, all played a part in this process.

“President Chávez launched the idea of the commune and has promoted its construction. But we are also governing in a state that is liberal bourgeois…. In a similar way, the economic foundations of the country are the same: rentier capitalism. We still live off of oil rents, and that generates a rentier subculture among political elites.”

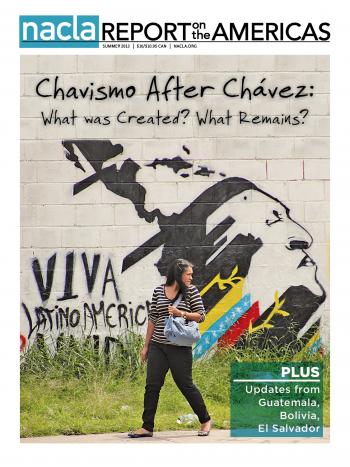

The underlying message of Maduro’s campaign was that he was closely tied to the Chávez legacy and would continue where his predecessor left off. Chávez began in 1999 with an emphasis on political reform and ended up embracing socialist rhetoric and promoting widespread expropriations. These transformations are likely to continue but perhaps at a slower pace.

The character of the Bolivarian process—Chavismo—lies in the understanding that social transformation can be constructed from two directions, “from above” and “from below.” Although not free of contradictions and conflicts, this two-track approach has been able to uphold and deepen the process of social transformation in Venezuela.

“I feel that women today have more self-esteem, more strength. They are familiar with this topic of rights, and this helps them change their relationships, to reconfigure the traditional role of woman.”