Home

“Free trade” and an aggressive military policy are central pillars of U.S. foreign policy. Better than any country in the world, Colombia demonstrates the intimate connection between these two aspects of U.S. power and their devastating results.

Teenage actors parade barefoot onstage, jumping and pounding drums. Others walk in with notebooks and briefcases overflowing with papers. Each actor spouts fragmented political speeches. The play depicts revolts and counter-revolts throughout Bolivian history, ending with a dramatic exchange between a mother and the ghost of her dead son, tortured during a dictatorship. “Don’t cry, Mom!” the ghost says. “I died bravely even though they gouged my eyes out and tore me apart. Don’t cry!”

Most U.S. labor unions agree on what to do about the some 12 million undocumented immigrants now living in the United States: Legalize their status. But sharp disagreements remain on the question of new immigrants, and the fault line lies mostly between unions in the Change to Win (CTW) coalition and the AFL-CIO.

“The question of power is not resolved by taking the government palace, which is easy and has been done many times, but rather by the building of new social relations,” said João Pedro Stedile, coordinator of Brazil’s Landless Rural Workers' Movement (MST), at the 2005 World Social Forum. His comment reflects a new vision of social change, one that until recently was almost exclusively promoted by the Zapatistas of Chiapas, but that has been gaining traction in prominent sectors of Latin America’s new social movements.

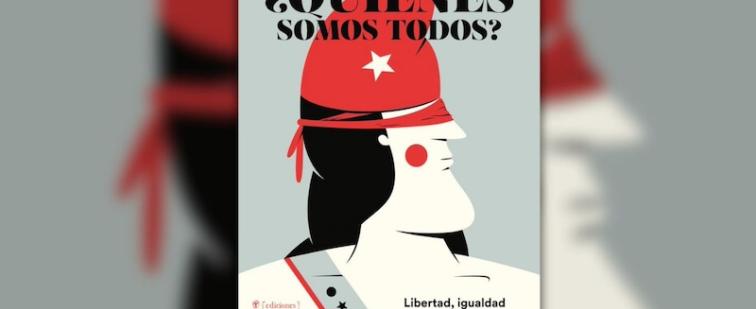

Impunity rides the coattails of amnesia and oblivion. Without memory to link the present with the past, current wrongs seem like historical aberrations, rather than the consequence of accumulated injustice. Authoritarian regimes and their allies know this well and are keen to snuff out those who reflect too thoughtfully on the past. By continually wiping the historical slate clean, they are free to do as they please and cover their tracks in the process.

As millions of immigrants and their supporters took to the streets last year, the anti-immigration movement mobilized its own forces. The number of state and local anti-immigration groups in the United States has exploded, growing by 600% in the last two years. In 2005, there were fewer than 40 groups; today, there are more than 250.

“We know that a rape or beating has certain effects on the victim. But growing up in a complete lie, with the possibility that those who raised you are your parent’s assassins or their accomplices, not even Freud had written anything about it.”

– Abel Madariaga, Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo Association.

Economist Pablo Dávalos served as undersecretary to Rafael Correa when the now-President was Minister of the Economy under the previous Administration of Alfredo Palacio in 2005. He’s an advisor to the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) and member of the Latin American Council of Social Scientists (CLACSO). Although he supported Correa’s successful presidential bid, he is skeptical of the direction the government is taking.

The last time NACLA devoted a report to immigration (“Welcome to America: The Immigration Backlash,” November/December 1995), we noted: “The roots of the backlash are essentially twofold: economic uncertainty and uneasiness about the country’s changing demographics.” While the themes of economic fear and nativism persist, today’s immigration battle is powerfully conditioned by two new factors: a boom in immigration, largely from Mexico, and the post-9/11 securitization of U.S. society.

One year since the country began to excavate common graves, chilling information has come to light: the “paras” (paramilitaries) gave courses on how to dismember a human body, the recently formed “Black Eagle” paramilitaries have been digging up graves and throwing the remains into the rivers and victims remain fearful.