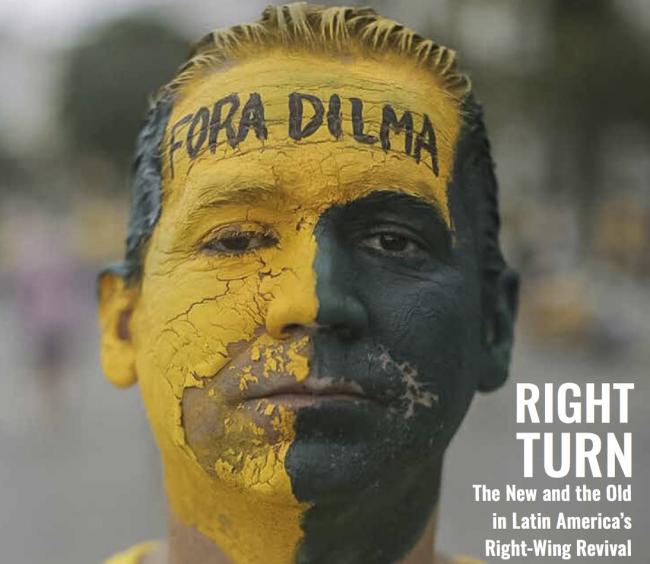

By now it’s undeniable: after over a decade of leftist governance, Latin America is in the midst of a major shift right. The evidence is everywhere, and striking. In Brazil, conservative elites capitalized on rising discontent over corruption and economic malaise to oust Dilma Rousseff under the thinnest of legal pretexts. In Argentina, a technocratic coalition stunned a long entrenched Peronism to handily win the presidency, and has since moved steadily to remake the country’s social and economic landscape in ways that threaten gains won by progressive social movements, labor activists, and the human rights community. In Colombia, former president Álvaro Uribe led an alliance of religious, economic, and political reactionaries to scuttle an historic chance at peace after decades of civil war—as clear an indication as any that the Right’s power is real and growing.

Less clear is what is new, and what is different, about this moment of right-wing ascendance from previous eras of conservative rule in the region. How, if at all, have right-wing politics adapted to changes in Latin America’s social landscape since the “pink tide” generated massive expectations of economic and political inclusion? What links together right-wing movements region wide, and what sets them apart from one country to the next? Ultimately, what does the Right mean today, and how can a better appraisal of its contours help the Left in Latin America and beyond organize in response?

These questions inform our latest NACLA Report. Our contributors consider both national-level experiences and regional implications of Latin America’s current right turn. We begin by probing the ideological foundations of the Right today. Despite more than a decade of policies privileging state-led development and social welfare, writes Barry Cannon, free market thinking thrives among regional elites. Moreover, its embrace by business leaders and politicians is primed to undo the policies progressive governments have advocated over the last decade.

Case in point: Honduras, where, as Beth Geglia writes, the “model cities” program launched following Manuel Zelaya’s 2009 overthrow has become a transnational crucible of neoliberalism, libertarian economic experimentation, and Cold War-era political authoritarianism. Meanwhile, in Brazil and Argentina, argue Benjamin A. Cowan and María Esperanza Casullo, respectively, history matters for understanding the rise of Michel Temer’s golpista coalition and Mauricio Macri’s Cambiemos government. There’s much that is “old” in the new Right, they find—specifically, the longstanding power of evangelicalism in Brazil and anti-populist elitism in Argentina. In his rhetoric, Argentina’s Macri has claimed to represent a more modern and even “compassionate” conservatism—voicing support for democracy and poverty reduction, for instance. However, his policies—from denigrating human rights groups to repressing social movements—suggest otherwise. In Brazil, supporters of Dilma Rousseff’s ouster launched unprecedented volleys of “brazen” and “unbridled” racist invectives on social media. This is not dissimilar to what Geraldo Cadava finds shapes right-wing U.S. politics today, though his conclusions lead elsewhere: whereas racism has bolstered the Right’s rise to power in Brazil, in the U.S., Donald Trump’s racist diatribes seem to be tearing apart a conservative movement founded with the help of many Latino politicians.

Beyond ideology, the issue situates the current right turn in a deeper, and more troubling, history. Bryan Pitts leads a roundtable discussion of Latin Americanist scholars to examine how the 2009 coup in Honduras heralded a regional right-wing revival, helping conservative politicians and movements adopt new tactics and pseudo-legal justifications to not only halt progressive policies but remove Left-populist governments from power altogether. Paraguayan activist and economist Gustavo Codas, in conversation with Alexander Main, sounds an optimistic note: the return of the Right does not mean the “end of a progressive cycle.” Instead, Codas argues, the Left profoundly changed the political playing field, making it difficult for the Right to rollback social and political gains in one fell swoop. And in their respective pieces on Venezuela, Bolivia, and Mexico, Timothy M. Gill, Emily Achtenberg, and John M. Ackerman look beyond the current conjuncture. As Venezuela’s crisis deepens on all fronts, Gill considers what its declining influence in regional politics and economic cooperation will mean. In Bolivia, after more than a decade in power, Evo Morales’ MAS coalition faces new challenges from within and without, but also new opportunities for addressing progressive shortcomings. And in Mexico, a country the pink tide largely passed over, Ackerman finds promising signs of an eventual Left revival.

To read the rest of this article and content from the issue, click here.