Alain Rouquié once argued that the 1979 Sandinista Revolution marked Central America’s entry into global modernity. While that may be an exaggeration, what is certain is that the historical and political importance of this event has not been accompanied by an academic reflection of similar magnitude. Cold War concerns still shape approaches to the Revolution. On one side of the political spectrum, we have a “great man” history, captured in the numerous memoirs of guerrilla commanders: heroism, audacity, and sacrifice. On the other hand, we have the traditional historiography inherited from the Cold War, which is full of commonplace stories about the ghost of international communism and Cuban tutelage over the continental left. Both perspectives erase the collective agency of multiple actors, Nicaraguan and transnational, subordinating them to pre-established narratives far removed from the evidence.

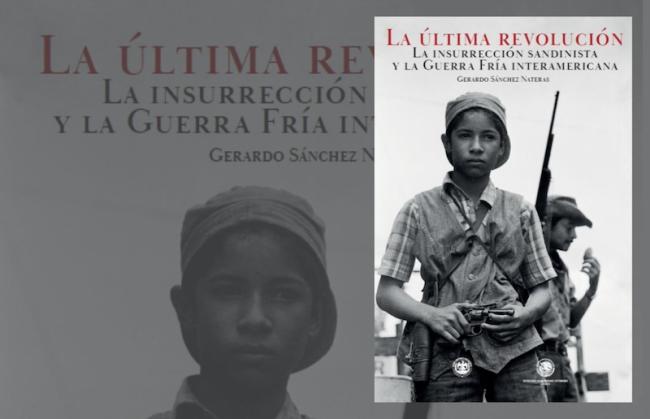

It is precisely to overcome these silences that the recent book by Gerardo Sánchez Nateras intervenes. Using an innovative overview of sources, Sánchez Nateras successfully suggests alternatives to the dominant narratives about the Nicaraguan revolution. Contrary to the apologetic memoirs of the Sandinista commanders, usually focused on highlighting the importance of popular unity, the author shows the rivalries between internal factions of the Sandinista Front. Thus, he highlights how the main tendencies within sandinismo—namely the Guerra Popular Prolongada (GPP), Tendencia Proletaria, and the Tendencia Tercerista—only reached minimum unity agreements in 1979, on the eve of the final victory. Rather than focus on the heroic memory of guerrilla combat, he highlights the skilled diplomacy—particularly of the Third Party faction—that achieved the political mobilization of an important sector of Nicaraguan economic elites and the formation of a broad coalition against Somoza within the Latin American landscape of the time.

Tercerista diplomacy deserves the prominent place Sánchez Nateras gives it in his research. This guerrilla tendency managed in a very short time to consolidate a robust policy of alliances that included the anti-Somoza bourgeoisie and the Christian left on the domestic front; and a diverse set of international supporters that transcended Latin America and included European social democracy, the Bulgarian foreign service, and “third position” governments such as those of Gaddafi in Libya or Hussein in Iraq.

And in contrast to the usual accounts of the Cold War, which perhaps overstate the influence of the United States and Cuba, Sánchez Nateras uncovers the vicissitudes of the Carter administration in Nicaragua, where its commitment to non-intervention led to an undesired result: a second Latin American revolution, after Cuba’s. He also shows the Sandinistas’s relative independence from the Cuban Communist Party’s famous Americas Department, founded to encourage revolutionary movements in Latin America, and their cold relations with several of the guerrillas in Central American countries.

It is noteworthy that Sanchez Nateras’s original arguments are based on his successful use of new primary sources. The author makes extensive use of the Central American archives of the U.S. Secretary of State, recently declassified and available in the repository of the National Security Archives of George Washington University. The book also makes extensive use of the Archivo Histórico “Genaro Estrada” of the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the general archives of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. In this way, Sanchez Nateras’s reconstruction of this period of regional history follows the most recent research tendencies on the Cold War in Latin America: to narrate it from Latin America itself, from Latin American sources, and from the agency of its multiple—and convoluted—regional actors.

In this regard, the research highlights two particularities of the moment that open new directions for future research: First, the formation of a sort of Latin American anti-Somoza front including the governments of Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, and Venezuela. The different motivations of their respective presidents did not prevent them from granting the opposition to Somoza—which ranged from sandinismo to conservative opposition groups—diplomatic, logistical, financial and, sometimes, military support.

Second, the imminence of an inter-American war in view of the regional tensions generated by the Sandinista advance in 1978-1979. The concern of the military governments of Central America— Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala—about the guerrilla advance in Nicaragua was supported by military dictators in the Southern Cone, as well as by Spain and Israel. The anti-Somoza commitment of the Panamanian and Venezuelan governments went as far as the practical deployment of troops, while the traditional Mexican policy of non-intervention—the so-called Estrada Doctrine—was set aside in the face of Mexico’s direct deterrence of the Guatemalan military. This situation of quasi-warfare shows the margin of maneuver of the governments of the time and opens new research questions about the particular diplomatic responses of the region.

In summary, La última revolución: La insurrección sandinista y la guerra fría interamericana is an interesting book both for general readers and for scholars of Central American history. Through its pages, one learns about the events that marked 1979's revolutionary outcome and the particular and complex regional conjuncture that shaped it. It also allows the opening of new discussions of inter-American international relations in the context of the global Cold War and a contextual vision of contemporary Central America.

Camilo Serrano Corredor is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE), Mexico.